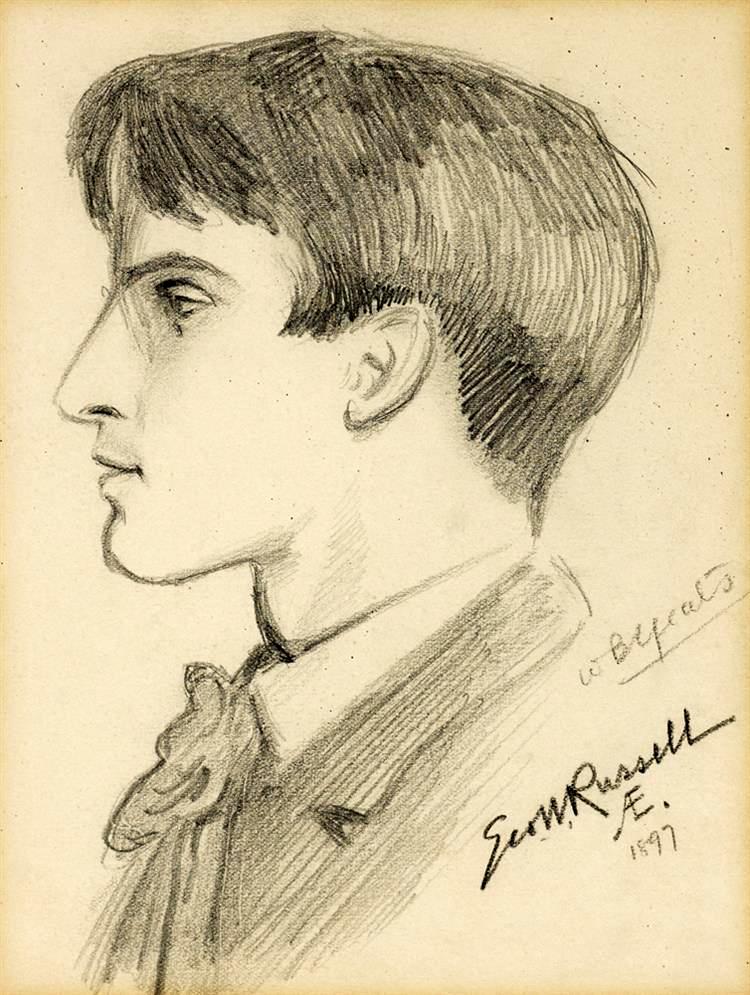

George William Russell, Irish legend in a crowded field, once published something under the pseudonym Æon but the printer cut off the last two letters and Æ liked the result. He did and was a lot of things, mainly between 1890 and 1930: painter, composer, agriculturalist, cyclist, pacifist, vegetarian, mystic, mentor, publisher. He published a weekly newspaper called The Irish Homestead intended mainly to support the rise of co-op farming but it wove in plenty of the Irish literary revival. How could he help it? Who could blame him.

George William Russell, Irish legend in a crowded field, once published something under the pseudonym Æon but the printer cut off the last two letters and Æ liked the result. He did and was a lot of things, mainly between 1890 and 1930: painter, composer, agriculturalist, cyclist, pacifist, vegetarian, mystic, mentor, publisher. He published a weekly newspaper called The Irish Homestead intended mainly to support the rise of co-op farming but it wove in plenty of the Irish literary revival. How could he help it? Who could blame him.

Æ gave James Joyce his start, asked him to write something simple. Joyce’s first published story “The Sisters” appeared in The Irish Homestead under the pseudonym Stephen Dedalus. It’s from a child’s point of view, so it seemed simple, of the wake and remembrance of a priest whose life was, you might say, crossed. That’s how Eliza puts it in the story. It’s what she doesn’t say that Æ didn’t like. He suggested Joyce tone the blasphemy and shocking stuff down a bit and try again, so Joyce being himself, called his next effort “Eveline” after a pornographic story popularly circulating about a girl who specializes in fellatio and has a sexual relationship with her father and other family members. Probably Æ didn’t make the connection. Did Joyce tone down the blasphemy? By blind, sniveling, nose-dropping, calumniated Christ, as Joyce has said and I say for him, he did not. Evelyn is a parody of St. Margaret Mary Alacoque, who likely irritated the other nuns in her convent by begging off sick any time there was work to do, but from whose sickbed visions came the Catholic devotion of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, to which Ireland was consecrated in the 1870s. Most Catholic families in Joyce’s time would have had a picture on the wall featuring the blessed Margaret Mary Alacoque, as Evelyn does. Evelyn is no Margaret Mary Alacoque. And the story? It does not paint a gentle picture of Irish nationalism as Æ would have hoped, no support of home rule nor elevation of Irish literary art. This was all about Irish paralysis, like everything else in Dubliners where these stories ended up.

Æ, supporter of talent, collector of poets and artists, gave Joyce one more shot. Joyce came back with a story set at an international car race held outside Dublin. The characters from different countries play out their national politics while the Irish spectators raise the cheer of the gratefully oppressed. His words. The Irish protagonist is left out of everything, gets blind stinking drunk, then in a card game the English and French guys fleece him for all he’s worth. Metaphor. Joyce called it the most important story in Dubliners. Æ stopped asking for stories. Joyce sometimes called him UI after that, for Urinary Infection? Wouldn’t put it past him. Joyce would say this, but maybe it’s Unemployment Insurance? Joyce borrowed money from Æ, it was A.E.I.O.U., until Æ said a touch of starvation would do Joyce good.

What did Joyce a great deal of good was Æ’s connections. Æ introduced him to W.B. Yeats, and Yeats’ secretary Ezra Pound, without whose efforts to promote his staggering smutty talent and generally to keep him alive and writing, James Joyce might have died an impoverished English teacher in Trieste. Thank you Æ, master mystic, you were a visionary artist supporting artists, who generously nurtured and promoted the work of dozens of talented people and opal hush poets. Joyce’s gratitude: “words cannot measure my contempt for Æ at present.” Well, ok. Joyce did feel a little salty about it when Æ wouldn’t lend him any more money, or send him the clothes and boots he had asked for, and though Joyce assumed, rightly, that Æ wouldn’t like his latest writing, Æ’s serene disapproval inspired Joyce to vow “so help me devil I will write only the things that approve themselves to me and I will write them the best way I can.” Hear hear, Jim, I completely get it.