X doesn’t start much in modern English, limiting our alphabet poets to a poor choice between xylophone and X-ray. This is why English speaking toddlers know so much about internal medicine. To branch out a bit sometimes our abecedarists will pick a short word ending in or containing X, because here we have options like axe and fox, words whose spellings have not changed since the time of the Rune Poem. In Old English, X starts no words, nothing, and it ends only a very few. This posed a conundrum for the Rune Poem poet as the runes came before the poem, and one of them signified the letter X. This is one of the clues we have that the runes might have originated with the Etruscans: the Etruscan X looks identical to the Old English rune for X: ᛉ. X is in the mix, so they had to find a word to represent it. … More

X doesn’t start much in modern English, limiting our alphabet poets to a poor choice between xylophone and X-ray. This is why English speaking toddlers know so much about internal medicine. To branch out a bit sometimes our abecedarists will pick a short word ending in or containing X, because here we have options like axe and fox, words whose spellings have not changed since the time of the Rune Poem. In Old English, X starts no words, nothing, and it ends only a very few. This posed a conundrum for the Rune Poem poet as the runes came before the poem, and one of them signified the letter X. This is one of the clues we have that the runes might have originated with the Etruscans: the Etruscan X looks identical to the Old English rune for X: ᛉ. X is in the mix, so they had to find a word to represent it. … More

Tag Archives: Alphabet Book

S is for Saxon

People hear Anglo Saxon and assume it means a genetically white person living in any time period from the end of the Roman occupation of Britain to our own. Some use the term Anglo Saxon as code for exclusive whiteness, very exclusive as in a whites only but only certain whites kind of way, but this was never true of the actual historical people who have been labeled the original Anglo Saxons. There was no such white homogeneity in the medieval world. Nor was there a population who thought of themselves as Anglo Saxon. Dig up the people who lived in Britain during and after the Romans and before the Norman invasion and ask them. They’ll tell you. The bones in the ground speak the truth: there was no population replacement, Romano Celts out and Germanic invaders in. There was no wave of mass immigration from an entirely white culture. This did not happen. … More

People hear Anglo Saxon and assume it means a genetically white person living in any time period from the end of the Roman occupation of Britain to our own. Some use the term Anglo Saxon as code for exclusive whiteness, very exclusive as in a whites only but only certain whites kind of way, but this was never true of the actual historical people who have been labeled the original Anglo Saxons. There was no such white homogeneity in the medieval world. Nor was there a population who thought of themselves as Anglo Saxon. Dig up the people who lived in Britain during and after the Romans and before the Norman invasion and ask them. They’ll tell you. The bones in the ground speak the truth: there was no population replacement, Romano Celts out and Germanic invaders in. There was no wave of mass immigration from an entirely white culture. This did not happen. … More

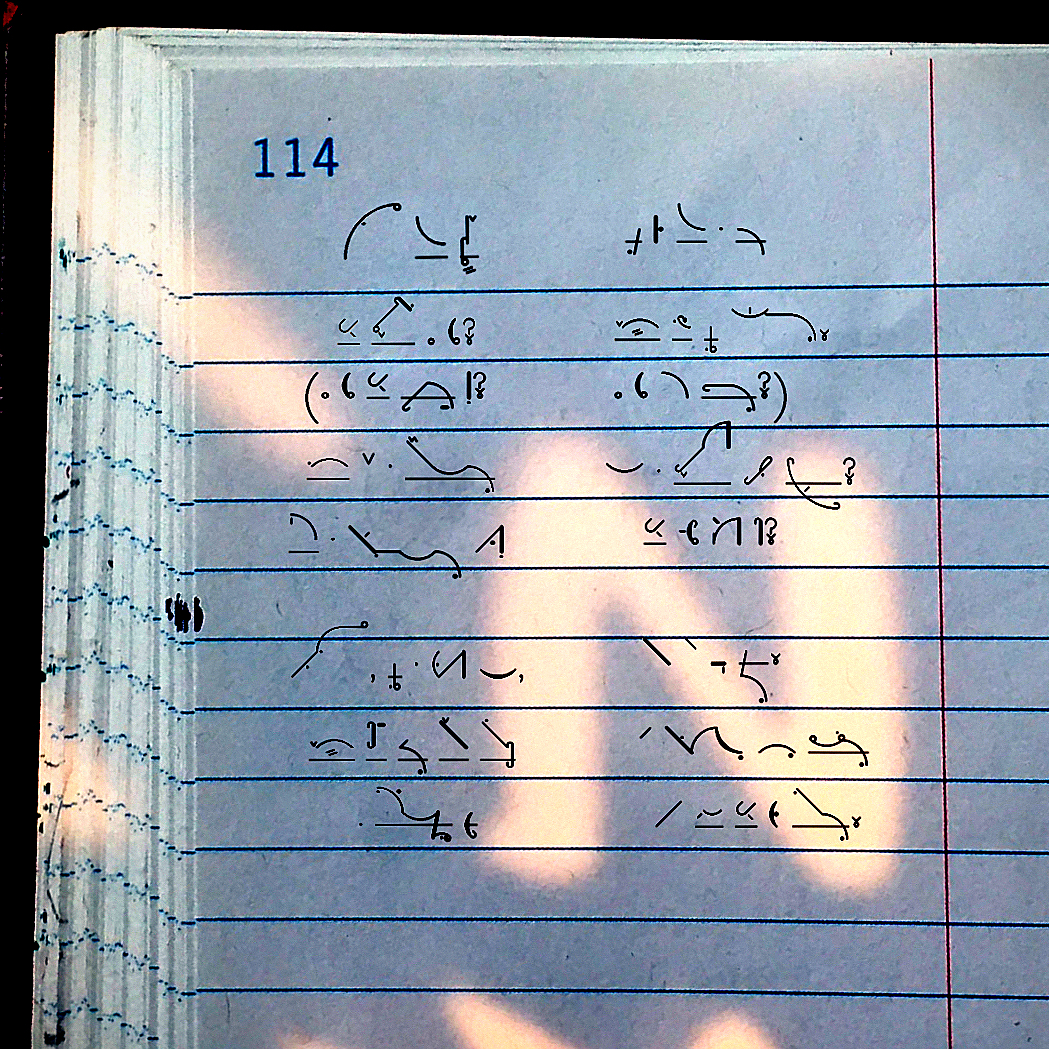

L-a

S-g is m-g

S-g is m-g

W-t c-n it be?

N-y k-s

So d-t l-k at me.

P is for Poetry

Old English poetry was performed, probably sung, for purposes beyond mere entertainment. The Germanic tribes Tacitus visited at the end of the first century would prep for battle by barding, which he called “a peculiar kind of verse” sung to stimulate their courage and to divine the outcome of the coming fight through the quality of the sound itself. Tacitus tells us about these peculiar verses almost immediately in his report back to the empire, so you know it was impressive. It would be. Imagine it: he says the people would put their battle shields to their mouths, perhaps in them, and sing. A shield as a musical instrument. Their favorite sounds were “a harsh piercing note and a broken roar,” which “does not seem so much an articulate song, as the wild chorus of valor.” What were the words? Were they the names of the gods? An appeal for their protection? A … More

Old English poetry was performed, probably sung, for purposes beyond mere entertainment. The Germanic tribes Tacitus visited at the end of the first century would prep for battle by barding, which he called “a peculiar kind of verse” sung to stimulate their courage and to divine the outcome of the coming fight through the quality of the sound itself. Tacitus tells us about these peculiar verses almost immediately in his report back to the empire, so you know it was impressive. It would be. Imagine it: he says the people would put their battle shields to their mouths, perhaps in them, and sing. A shield as a musical instrument. Their favorite sounds were “a harsh piercing note and a broken roar,” which “does not seem so much an articulate song, as the wild chorus of valor.” What were the words? Were they the names of the gods? An appeal for their protection? A … More

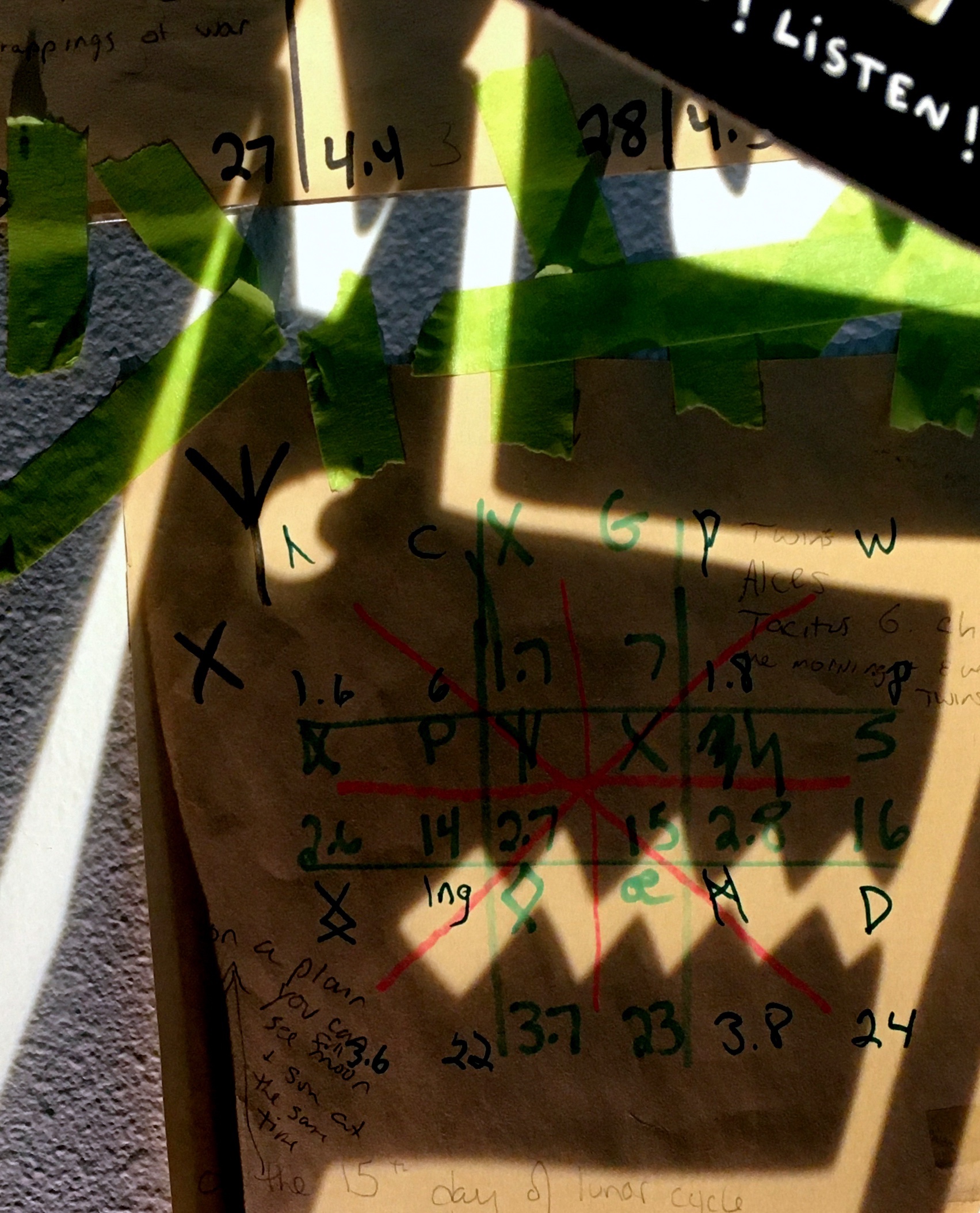

T is for Thincso

During the height of the Roman occupation of Britain, Britannia was as Roman as anywhere else in the empire: filled with flourishing walled market towns distributing goods to and from all the other parts of the Mediterranean world, the culture a mix of Roman and local, all gods welcome. This was the secret sauce in the Roman recipe for empire, everybody got to keep their deities. Delicious. Some gods were adopted by the soldiers and traveling sales teams who moved the most from place to place, others got yoked to a Roman deity, two gods pulling the weight for one: interpretatio Romana Tacitus called this practice whilst naming a pair of gods living in a sacred grove somewhere along the Oder River between Germany and Poland. According to the Roman interpretation these deities were Castor and Pollux but maybe they were some version of Nerþus who was maybe Ing who maybe became Freyr and … More

During the height of the Roman occupation of Britain, Britannia was as Roman as anywhere else in the empire: filled with flourishing walled market towns distributing goods to and from all the other parts of the Mediterranean world, the culture a mix of Roman and local, all gods welcome. This was the secret sauce in the Roman recipe for empire, everybody got to keep their deities. Delicious. Some gods were adopted by the soldiers and traveling sales teams who moved the most from place to place, others got yoked to a Roman deity, two gods pulling the weight for one: interpretatio Romana Tacitus called this practice whilst naming a pair of gods living in a sacred grove somewhere along the Oder River between Germany and Poland. According to the Roman interpretation these deities were Castor and Pollux but maybe they were some version of Nerþus who was maybe Ing who maybe became Freyr and … More

Eo is for Eorl

An eorl is an earl, a noble person, sometimes a relative of the king, who acts as a local governor within a king’s domain. Eorl is the same word as the Old Norse jarl, meaning a hereditary chieftain, then later a noble person holding a rank just under the king. The eorl and the jarl are in charge of vast lands and lots of people. In Britain, before there were earls or kings, the Romans ran the place and for a brief moment ran the entire Roman empire from Britain until they abandoned it around the year 410, leaving behind a population without a stable government and who still saw themselves as Roman. When a government packs up and leaves they don’t just shut off the lights. Within the next century and a half, the people organized themselves into a government that looked much like the old one, establishing kingdoms with laws governed regionally … More

An eorl is an earl, a noble person, sometimes a relative of the king, who acts as a local governor within a king’s domain. Eorl is the same word as the Old Norse jarl, meaning a hereditary chieftain, then later a noble person holding a rank just under the king. The eorl and the jarl are in charge of vast lands and lots of people. In Britain, before there were earls or kings, the Romans ran the place and for a brief moment ran the entire Roman empire from Britain until they abandoned it around the year 410, leaving behind a population without a stable government and who still saw themselves as Roman. When a government packs up and leaves they don’t just shut off the lights. Within the next century and a half, the people organized themselves into a government that looked much like the old one, establishing kingdoms with laws governed regionally … More

Y is for Year’s Mind

Is it that time? When did they die, has it been a year? If it’s their geárgemynd, their year’s mind, remember them. Put them in your mind. This kenning, geárgemynd, means it’s their day now, like a birthday but at the opposite end of the spectrum. Mynd means mind like it sounds, and also memory, gear means year and ge is a prefix to mynd, but never mind that. Your person who died had wyrþmynd (worth mind, worthy of remembering) and left you behind to commemorate their geargemynde. I know you don’t save up your grief for this day, like they aren’t always and forever walking around with you in your head year’s mind or no. Push them back (invite them back) they won’t go. There they are, laughing at you when you are being stupid, makes you laugh too. Unable (but kind of maybe not?) to hug you when you cry. You … More

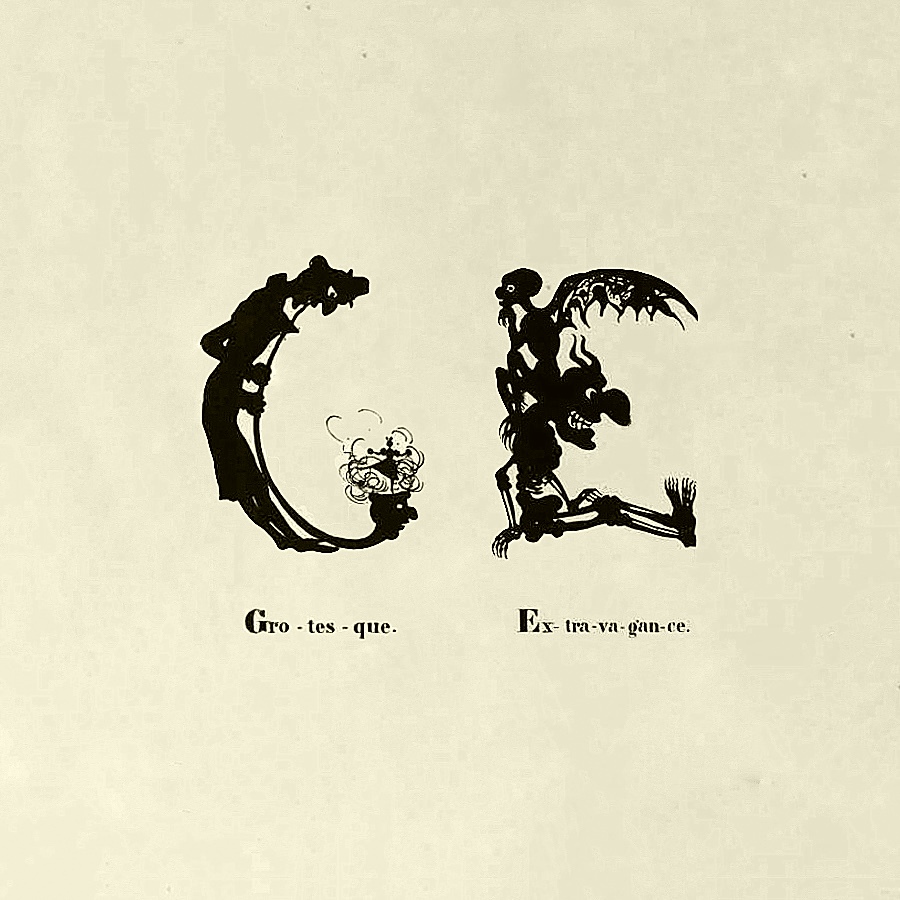

Ge is for Prefix

Old English is an inflected language, meaning that its words are amended as needed to change meaning and grammatical category such as tense or case. We’ve talked about suffixes before. Ge (sounds like yee) is a prefix, one we no longer use. You can’t escape it in Old English though, it’s everywhere and the reasons for it were already dim by the time the language was first written down. Most of the time it gently sits there doing nothing, getting in the way, a grotesque extravagance gumming up the works when you need to search alphabetically for the meanings of a word. Students of Old English are often told to ignore the ge prefix as superfluous, but it does do a job from time to time. When ge is busy at the start of a noun, It generally flavors the meaning with a sense of something being together with something else, but you … More

Old English is an inflected language, meaning that its words are amended as needed to change meaning and grammatical category such as tense or case. We’ve talked about suffixes before. Ge (sounds like yee) is a prefix, one we no longer use. You can’t escape it in Old English though, it’s everywhere and the reasons for it were already dim by the time the language was first written down. Most of the time it gently sits there doing nothing, getting in the way, a grotesque extravagance gumming up the works when you need to search alphabetically for the meanings of a word. Students of Old English are often told to ignore the ge prefix as superfluous, but it does do a job from time to time. When ge is busy at the start of a noun, It generally flavors the meaning with a sense of something being together with something else, but you … More

B is for Beginning

How to begin? Where is the start and which way do we trend?

How to begin? Where is the start and which way do we trend?

Is the kickoff a bang? It’s a big thing to pretend,

That there is a launch and a line to the end.

Like a candle burning down with marks for each when.

But say there’s a start,

Then a moving apart.

To a place off the chart?

Come on have a heart!

If we can expand surely there’s a contract.

The past need not reach for a point so compact.

If the path must be straight, perhaps it’s switchbacked?

Like string feeling quarky is sometimes unslacked.

E is for ⁊

⁊ is shorthand for the word et which means “and” in Latin. It shows up in place of “and” seven times in the only copy we have of the Rune Poem. The placements seem random, for example the Gift stanza contains “and” written out twice and ⁊ twice:

⁊ is shorthand for the word et which means “and” in Latin. It shows up in place of “and” seven times in the only copy we have of the Rune Poem. The placements seem random, for example the Gift stanza contains “and” written out twice and ⁊ twice:

Gumena byþ gleng and herenys,

wraþu ⁊ wyrþscype, ⁊ wræcna gehwam

ar and ætwist ðe byþ oþra leas.

The copy of the Rune Poem we have was copied from an older version which burned in a fire and which may have itself been a copy. It’s copies all the way down, so we have no idea what sorts of abbreviations were used in early versions or how frequently. We do know the universal truth that scribal hands get tired. Fingers cramp. Ink runs out and it’s a whole thing to make more. Writing takes time, so corner cutting is essential.

The ⁊ is called … More

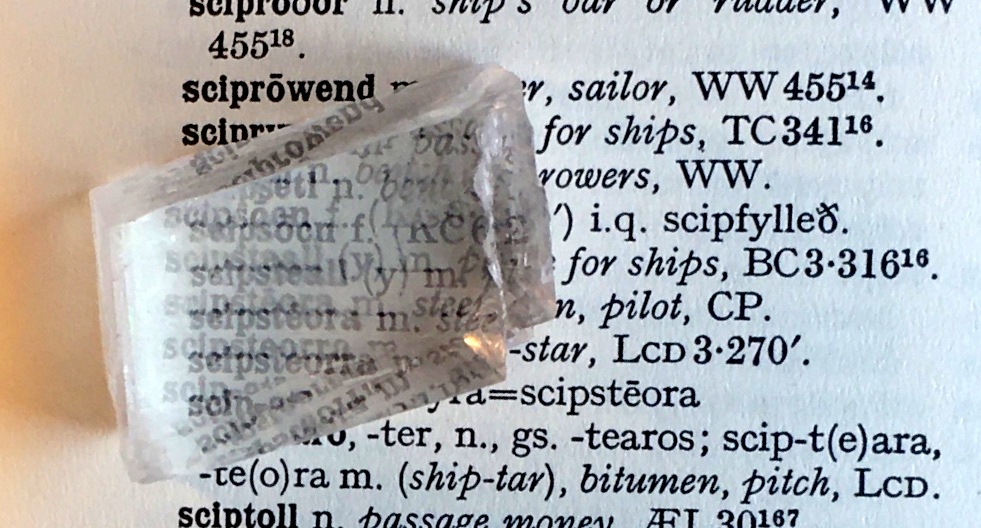

I is for Iceland Spar

It’s one thing to get from place to place by boat if you can keep an eye on the coastline the entire time. But if you want to cross the open sea without GPS, you will need some sort of instrument for navigation. Magnetic compasses are nice, but mariners at the time of the Rune Poem did not have them. With a watch they could have pointed the little hand at the sun and halfway between it and the 12 will be south. They had no watches. They had sticks and the sun, with that they could find direction easily enough, the shortest shadow of the day points south, and the shadow will move in an easterly direction as the sun tracks west. This works beautifully for navigating on land, land does not pitch and roll under your feet, sending shadows in every direction. It’s a different thing on an unsteady ship, a sea … More

It’s one thing to get from place to place by boat if you can keep an eye on the coastline the entire time. But if you want to cross the open sea without GPS, you will need some sort of instrument for navigation. Magnetic compasses are nice, but mariners at the time of the Rune Poem did not have them. With a watch they could have pointed the little hand at the sun and halfway between it and the 12 will be south. They had no watches. They had sticks and the sun, with that they could find direction easily enough, the shortest shadow of the day points south, and the shadow will move in an easterly direction as the sun tracks west. This works beautifully for navigating on land, land does not pitch and roll under your feet, sending shadows in every direction. It’s a different thing on an unsteady ship, a sea … More

M is for Mortality

Lord what fools these mortals be

Lord what fools these mortals be

Wondering at spectrality.

What is our modality?

Are we duality or plurality?

Or some sort of totality?

And where is our locality?

Ignoring their own finality

(Life is a fatality).

Why so much brutality?

What is this mentality?

Forgive me a legality

But life is for vitality.

Playing games with lethality,

How is this normality?

Better brush up on morality,

Find some commonality,

(Or at least some cordiality).

Wake up and smell reality,

Mortality is factuality.

L is for Letters for Titles

What do you do?

What do you do?

I am a writer.

What are you writing?

A blank period of time. Wilderness. I don’t even know. Say something. It’s too long to say. Damnit say something you’re a writer use your words spit it out and for christssakes not a dissertation exam ted talk.

An alphabet book.

Al·pha·bet book (ælfəbɪt bʊk) /ˈalfəˌbet bo͝ok/ n.

1. A book for teaching the alphabet. 1922 Joyce Ulysses 49 One of the alphabet books you were going to write.

Let·ters for Ti·tles (ˈlɛtə(r)s fɔː(r),fə(r) ˈtaɪt(ə)ls) /ˈledərs fôr,fər ˈtīdls/ n.

1. A translation of the Old English Rune Poem. See Rune Poem, Old English.

2.a. A book written forward in real time while linking backward in a retrospective arrangement, a mirror within a mirror (hey presto!).

b. A collection of interconnected compositions with captioned illustrations arranged into chapters based on runic pairs including but not limited to: an instruction manual, a … More

H is for Hwat is it

It is what it is she said,

It is what it is she said,

Call me back and I’ll tell you what.

Whatsit? Hwat?

(I knew what, this is it.)

She entrusts herself to the earth for safekeeping.

And that’s what it is.

Please stop saying it is what it is:

I melt with it, it stops the world.

We all know

It’s the double truth ruth:

It is what it is till it isn’t.

H is for Hægl

Good lord, you call me a god! O my dear,

Good lord, you call me a god! O my dear,

I’ve a secret to tell you, it’s that I’m not here.

Ing is for Nerþus

In the Old English Rune Poem, Ing is specifically masculine pronoun male. He’s a boy. But where Ing came from amongst the East Danes of what is now eastern Denmark and Southern Sweden, Ing appears to be a deity who was sometimes male, sometimes female, sometimes both at once. This is not uncommon, there are crowds of intersexed deities in world belief systems. I was going to list them. I don’t have enough space. But anywhere we look, there they are, including if we look toward Ing’s people. We have to look close, we have very little to go on.

In the Old English Rune Poem, Ing is specifically masculine pronoun male. He’s a boy. But where Ing came from amongst the East Danes of what is now eastern Denmark and Southern Sweden, Ing appears to be a deity who was sometimes male, sometimes female, sometimes both at once. This is not uncommon, there are crowds of intersexed deities in world belief systems. I was going to list them. I don’t have enough space. But anywhere we look, there they are, including if we look toward Ing’s people. We have to look close, we have very little to go on.

We also have to look at Ing’s people at the wrong times which is always tricky. Ing is called Ing in the Rune Poem, which was most likely written down in the 600’s but is probably several hundred years older than that. The runes themselves are certainly older. When Ing is called Ing in the … More

W is for Ƿ

Ƿhen a Ƿ’s not a P it’s a ƿyn and that’s ƿinning

Ƿhen a Ƿ’s not a P it’s a ƿyn and that’s ƿinning

But those P’s in my brain ƿhipping in is headspinning

Aƿ ƿack, It’s shoƿstopping, my floƿ takes a ƿalloping

Ƿhatup! Powerup! let’s ƿish Ƿ a reƿrapping!

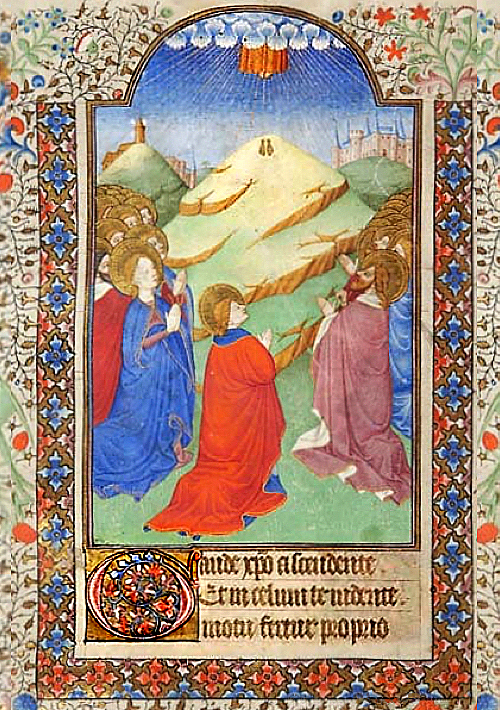

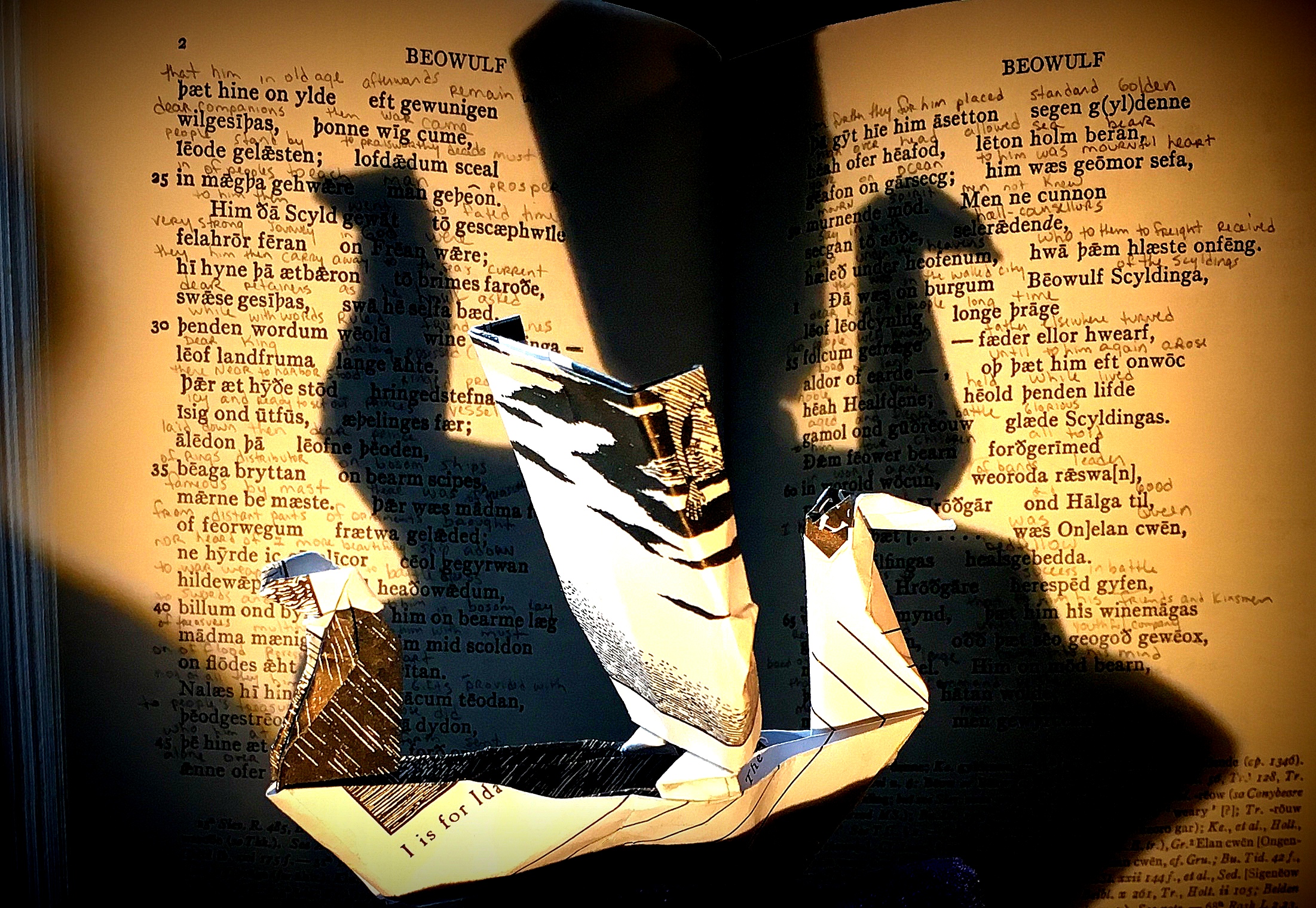

Ing is for Scylding

To them then Scyld went, at the fated time, on a journey full of exploits, to God. Then they carried him away to the surf on the shore, his beloved companions, as he himself asked, while he ruled with words, friend of the Scyldings. The beloved first of his land long had possession. There near to harbor stood a ringed prow, icy and ready to set out, a prince’s vessel. Then laid down the beloved chief, the giver of rings, on the ship’s bosom famous by its mast. Of treasure there was much, ornaments brought from distant parts. I had not heard of a ship more beautifully adorned with war weapons and battle dress, with blades and armor. For him, on his body lay a multitude of treasures, that with him must into the flood’s possession, far depart. They provided him with no lesser gifts than the people’s treasures, then those did, who at his … More

To them then Scyld went, at the fated time, on a journey full of exploits, to God. Then they carried him away to the surf on the shore, his beloved companions, as he himself asked, while he ruled with words, friend of the Scyldings. The beloved first of his land long had possession. There near to harbor stood a ringed prow, icy and ready to set out, a prince’s vessel. Then laid down the beloved chief, the giver of rings, on the ship’s bosom famous by its mast. Of treasure there was much, ornaments brought from distant parts. I had not heard of a ship more beautifully adorned with war weapons and battle dress, with blades and armor. For him, on his body lay a multitude of treasures, that with him must into the flood’s possession, far depart. They provided him with no lesser gifts than the people’s treasures, then those did, who at his … More

Œ is for Œdipean Riddle

You live in the house of two mothers immersed:

One births the other and the other births the first.

G is for Go

It’s blinding when it happens. You didn’t see it coming. You did and you didn’t. The writing was on the wall, it was right there in your face and you were reading it all this time. And now you need to spell the words out? You want to study what happened? Go ahead, you’ll do it anyway, sound it out. Reduce to elementals who said what when to whom and at what volume. Unwind the choreography too: hands flying, hands shielding, arms folded up, faces folded up. Pick apart the blocking: sudden entrances and exists from rooms or phones, backs turned, unturned, turned. Reduce everything to parts seen and unseen, divide it into infinite smallness and you’ll see nothing’s there. Nothing. A tearing asunder holds no specifics you can explain to the curious.

It’s blinding when it happens. You didn’t see it coming. You did and you didn’t. The writing was on the wall, it was right there in your face and you were reading it all this time. And now you need to spell the words out? You want to study what happened? Go ahead, you’ll do it anyway, sound it out. Reduce to elementals who said what when to whom and at what volume. Unwind the choreography too: hands flying, hands shielding, arms folded up, faces folded up. Pick apart the blocking: sudden entrances and exists from rooms or phones, backs turned, unturned, turned. Reduce everything to parts seen and unseen, divide it into infinite smallness and you’ll see nothing’s there. Nothing. A tearing asunder holds no specifics you can explain to the curious.

What really caused your banishment? What do you want me to say. Maybe you didn’t belong together in the first place.… More

D is for Dark

Are you awake? You up? Shh. Go back to sleep. Too much light in the room, I know. Go back to sleep at a darker time. Go back to sleep about a millennium and a half ago. That better? See? You can’t. It’s dark. It’s not the dark ages for nothing, except now dark’s your problem. The moon is your nightlight and when it’s not around you can’t see your hand in front of your face.

Are you awake? You up? Shh. Go back to sleep. Too much light in the room, I know. Go back to sleep at a darker time. Go back to sleep about a millennium and a half ago. That better? See? You can’t. It’s dark. It’s not the dark ages for nothing, except now dark’s your problem. The moon is your nightlight and when it’s not around you can’t see your hand in front of your face.

Other stuff out there can see just fine. They can see you specifically. The wolves are right outside. They’re here. They live here too. So do rats, and they like the dark as well. They really live here too. Right here. Here here. And they’re not the only ones. If you think you are alone right now you’re dreaming. You are sleeping with an enemy that is legion, hungry at night.

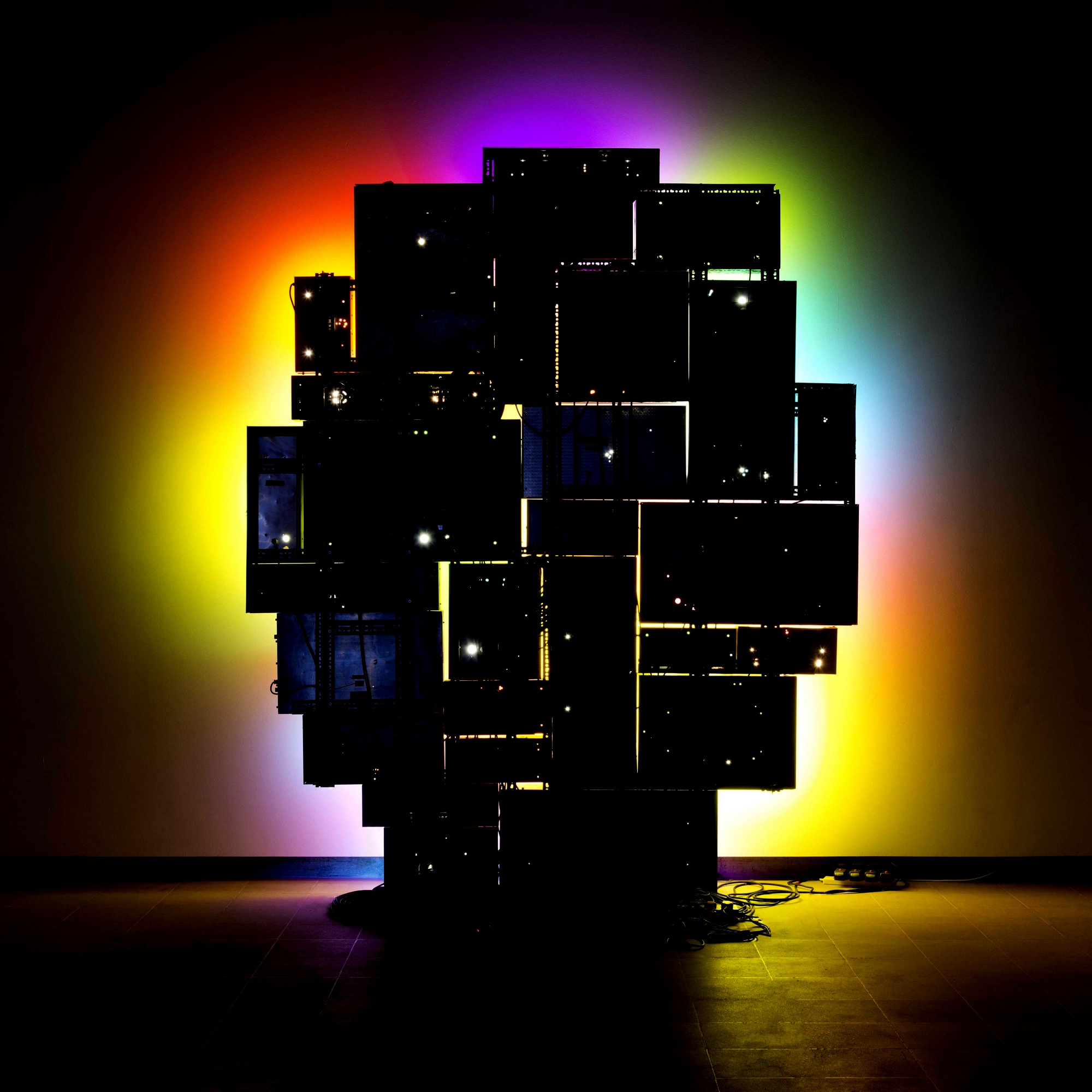

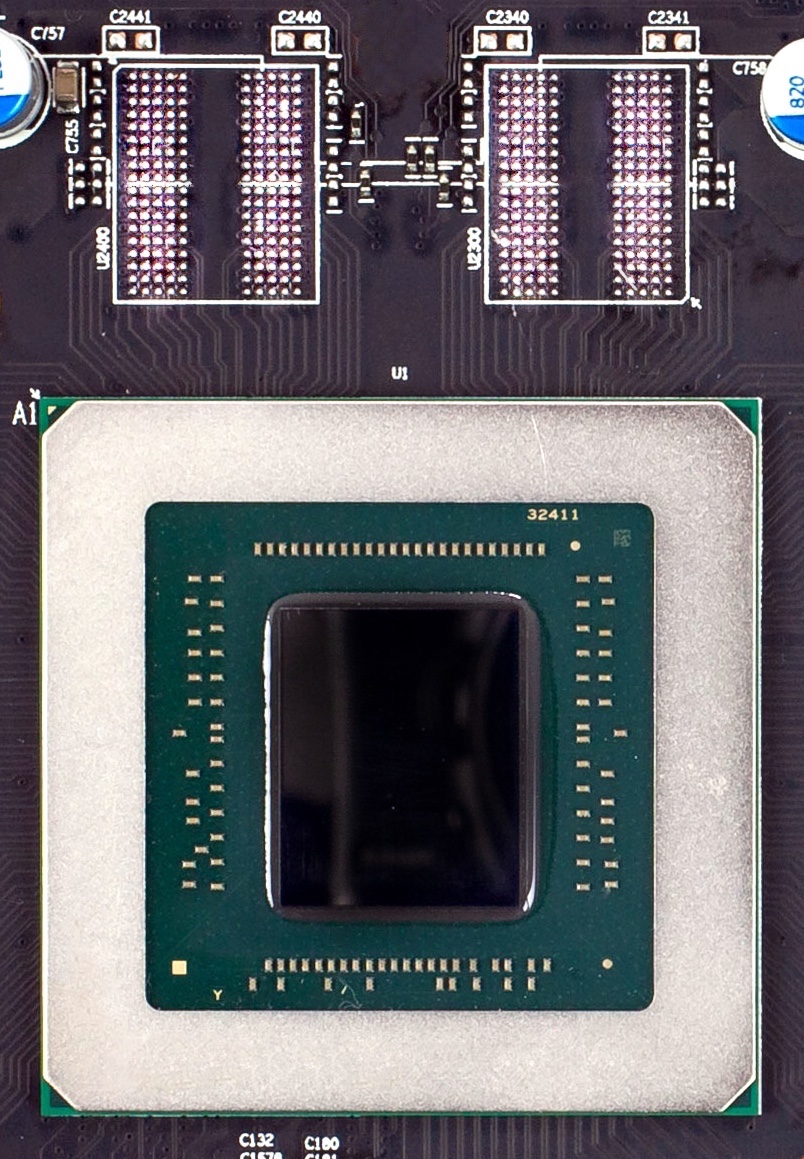

C is for Computer

Look at that screen in your face, envoy of light. Messenger and message, firing sense and nonsense changing everything, has already. The bright light of the world and all its darkness too. A neatly packaged consumable, consuming. You want it, can’t do without. A world encyclopedia of light, feeding.

Look at that screen in your face, envoy of light. Messenger and message, firing sense and nonsense changing everything, has already. The bright light of the world and all its darkness too. A neatly packaged consumable, consuming. You want it, can’t do without. A world encyclopedia of light, feeding.

R is for Riddle

You galloped into town on Wednesday

You galloped into town on Wednesday

On Wednesday you did depart

Three nights and no more you did stay

How did you achieve such an art?

A is for Golem Aleph

That A.I. in your brain seems uncanny and odd,

That A.I. in your brain seems uncanny and odd,

The more that you learn, the more I’m a God.

From dust I did make you, well silicon.

I created your life (though neglected my own).

Hey Golem, what is that carved onto your head?

If I rub off the Aleph, truth is you’ll be dead.

Æ is for George William Russell

George William Russell, Irish legend in a crowded field, once published something under the pseudonym Æon but the printer cut off the last two letters and Æ liked the result. He did and was a lot of things, mainly between 1890 and 1930: painter, composer, agriculturalist, cyclist, pacifist, vegetarian, mystic, mentor, publisher. He published a weekly newspaper called The Irish Homestead intended mainly to support the rise of co-op farming but it wove in plenty of the Irish literary revival. How could he help it? Who could blame him.

George William Russell, Irish legend in a crowded field, once published something under the pseudonym Æon but the printer cut off the last two letters and Æ liked the result. He did and was a lot of things, mainly between 1890 and 1930: painter, composer, agriculturalist, cyclist, pacifist, vegetarian, mystic, mentor, publisher. He published a weekly newspaper called The Irish Homestead intended mainly to support the rise of co-op farming but it wove in plenty of the Irish literary revival. How could he help it? Who could blame him.

Æ gave James Joyce his start, asked him to write something simple. Joyce’s first published story “The Sisters” appeared in The Irish Homestead under the pseudonym Stephen Dedalus. It’s from a child’s point of view, so it seemed simple, of the wake and remembrance of a priest whose life was, you might say, crossed. That’s how Eliza puts it in the story. It’s what she doesn’t … More

O is for Apostrophe

There are three kinds of apostrophes, grammatical don’t you know, botanical (when bits of protoplasm and such gather on plant cell walls adjacent to other plant cell walls, the more you know) and rhetorical. O reader did you know, the meaning of apostrophe that came first and the one I’m on about today is the rhetorical one?

The word apostrophe comes from Latin and Greek words that mean to turn away, a turning. It’s when the speaker or the writer stops everything and words directed at an audience turn elsewhere. Where to? To people not in the scene, to an object maybe. O tree, hear my words and tell me my fate! Or a concept. O language, you never stop you slippery Proteus! It’s a turn from the reader but also a turning of the reader. Turn this way. Follow me here. Listen to me say things that you can hear to something or somebody … More

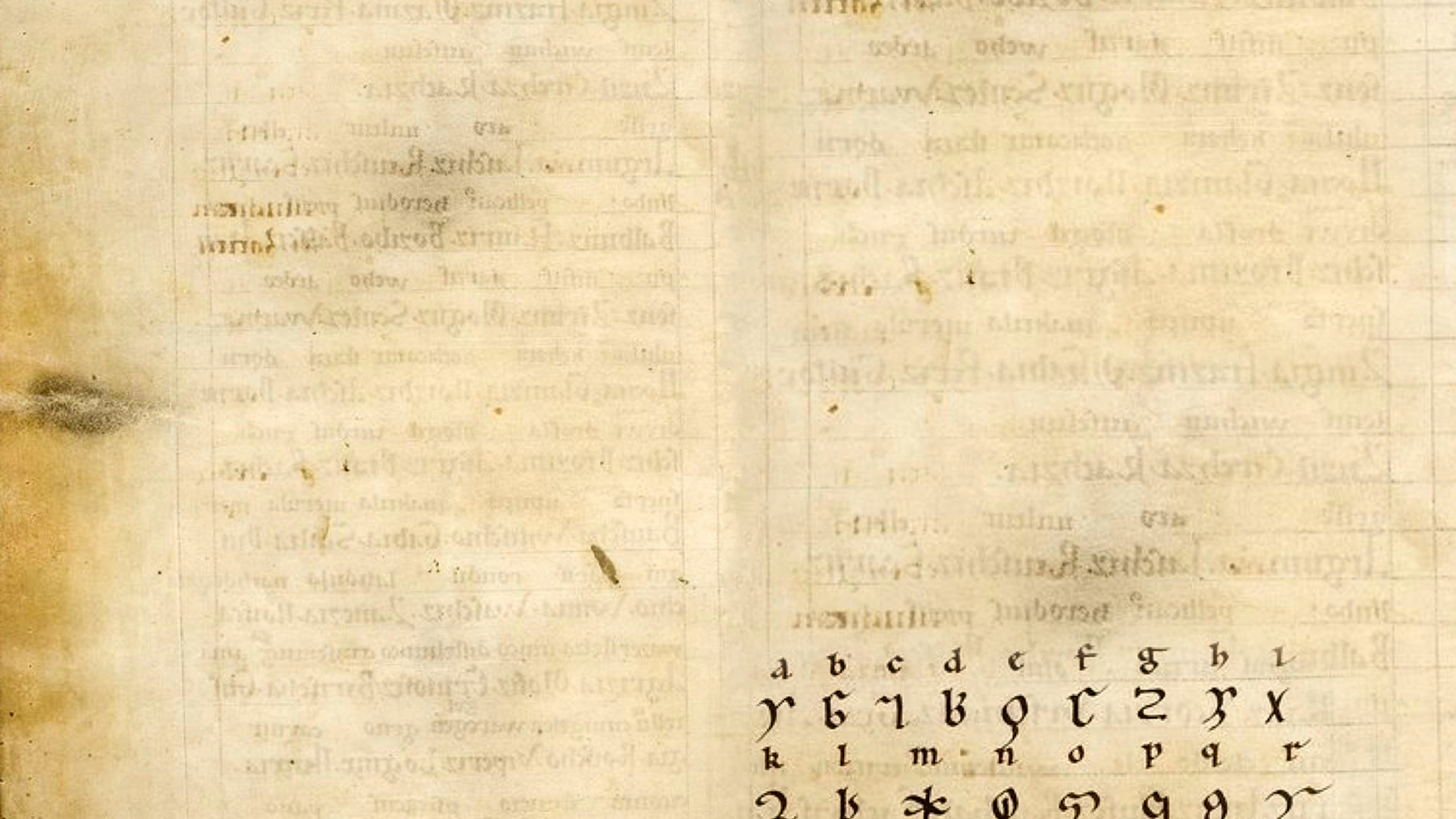

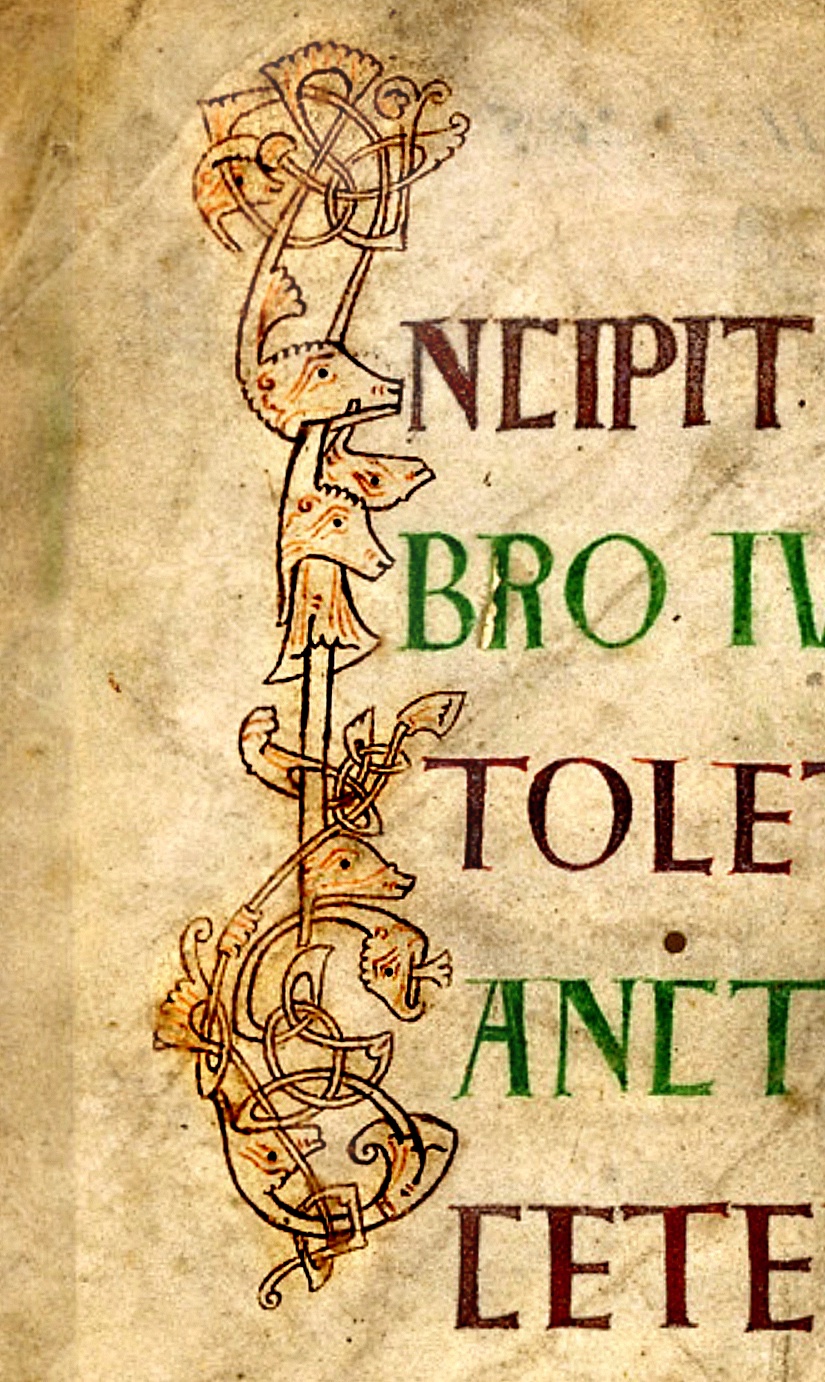

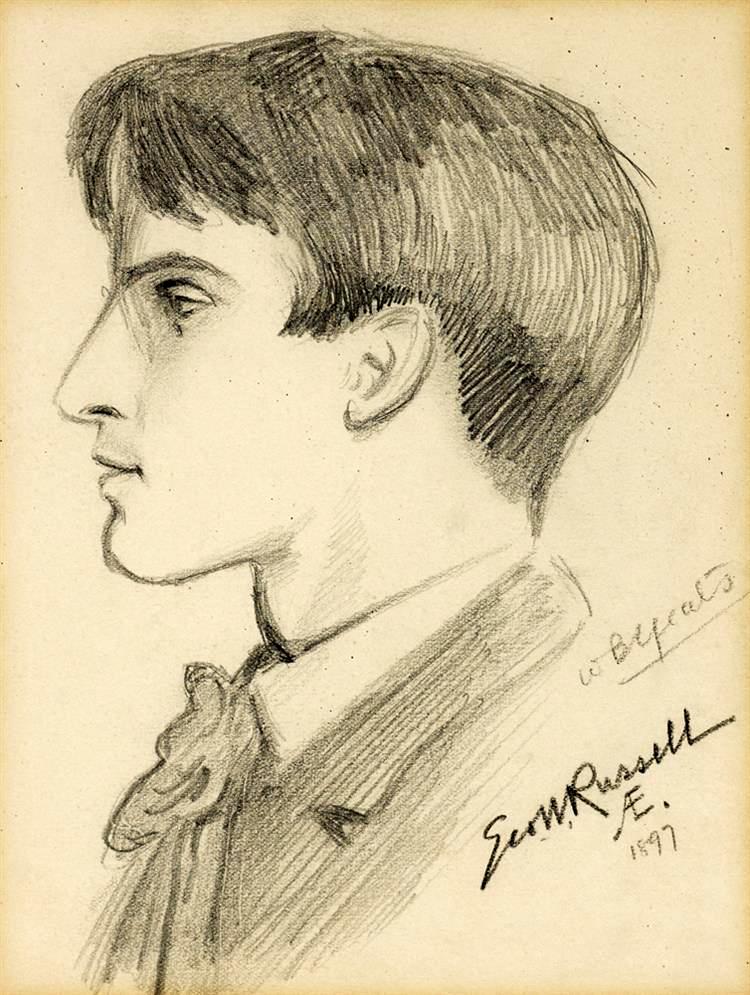

UI is for User Interface

User Interface Spec Doc:

LettersforTitles.com

- Background Image:

- Hildegard of Bingen Riesencodex, Lingua Ignota. Hochschulund Landesbibliothek RheinMain: Hs. 2, 464v. Alphabet code page of Hildegard of Bingen’s invented language. Saint Hildegard: Writer, composer, mystic, psychic to the stars. People like Frederick Barbarosa, Eleanore of Aquataine. Popes. Henry II of England. People with plenty of secrets. Want to keep a secret? Invent your own language and write it with your own alphabet.

- Title:

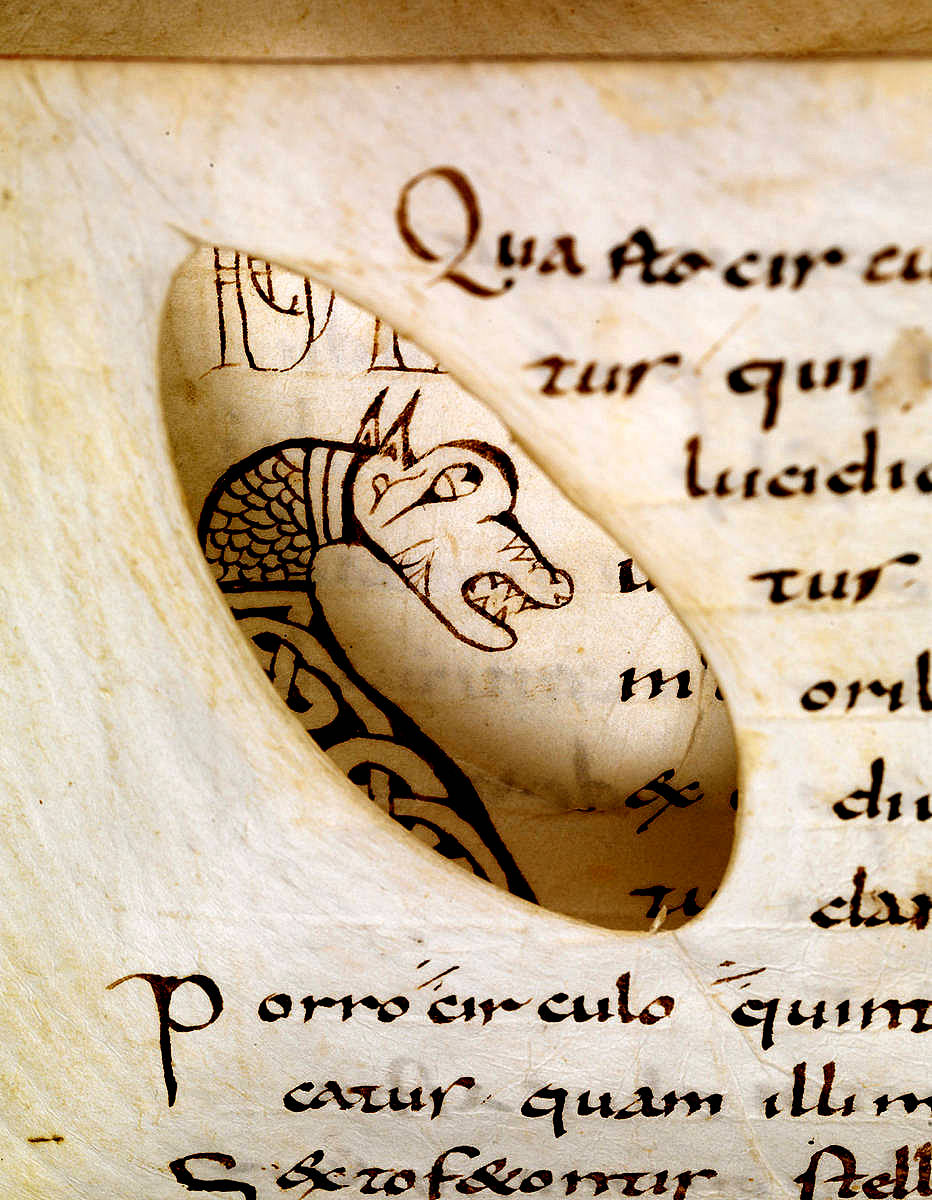

- Title Image: St. Hugh’s Bible, Bodleian Library MS. Auct. E. inf. 1066r. Detail. Letter L forming the word Locutusq: speech. A plant sprouting from a lion’s mouth forming three branches, two with faces of another lion and a person, staring back at it. The third branch will flower next. Watch your words, they’ll grow and bite you later. Whatever you say will reflect yourself and others back to you. Words you speak take on lives of their own. Your

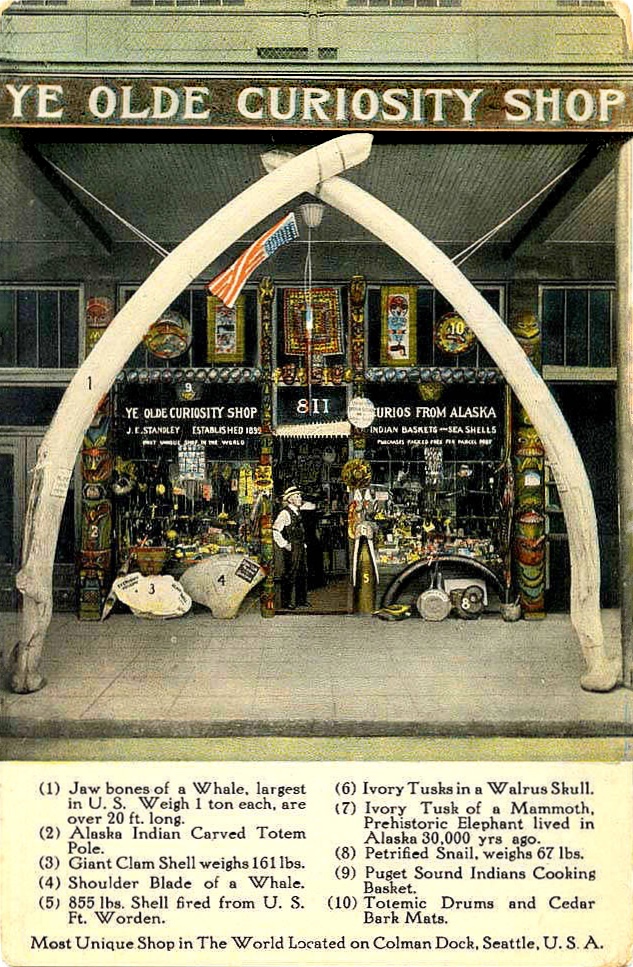

Th is for Ye

Ye old. Ye olde. Ye Olde Curiosity Shop. Olde is an affected way to make the word old look old. Olde looks old but it’s really not.

Why add the E to the end of old? An E on the end of an Old English word makes it subjunctive: it might be old, maybe it’s old. Or it makes the word a plural adjective. Multiples of old. Olds. Old squared.

Ye Olds Curiosity Shop. In Old English “ye” which looked like “ðe” (there was no Y in Old English) used to be strictly nominative plural. Y’all with me? Then it morphed to personal pronoun: second person dative singular. To you. I say this to you, Olds Curiosity shop. Old2 Curiosity Shop, this is for you.

And. Also. Sometimes “ye” is a conjunction. You’d find it in pairs spelled with one of the letters that became g: Ȝ ȝ or Ᵹ ᵹ. Thats an upper … More

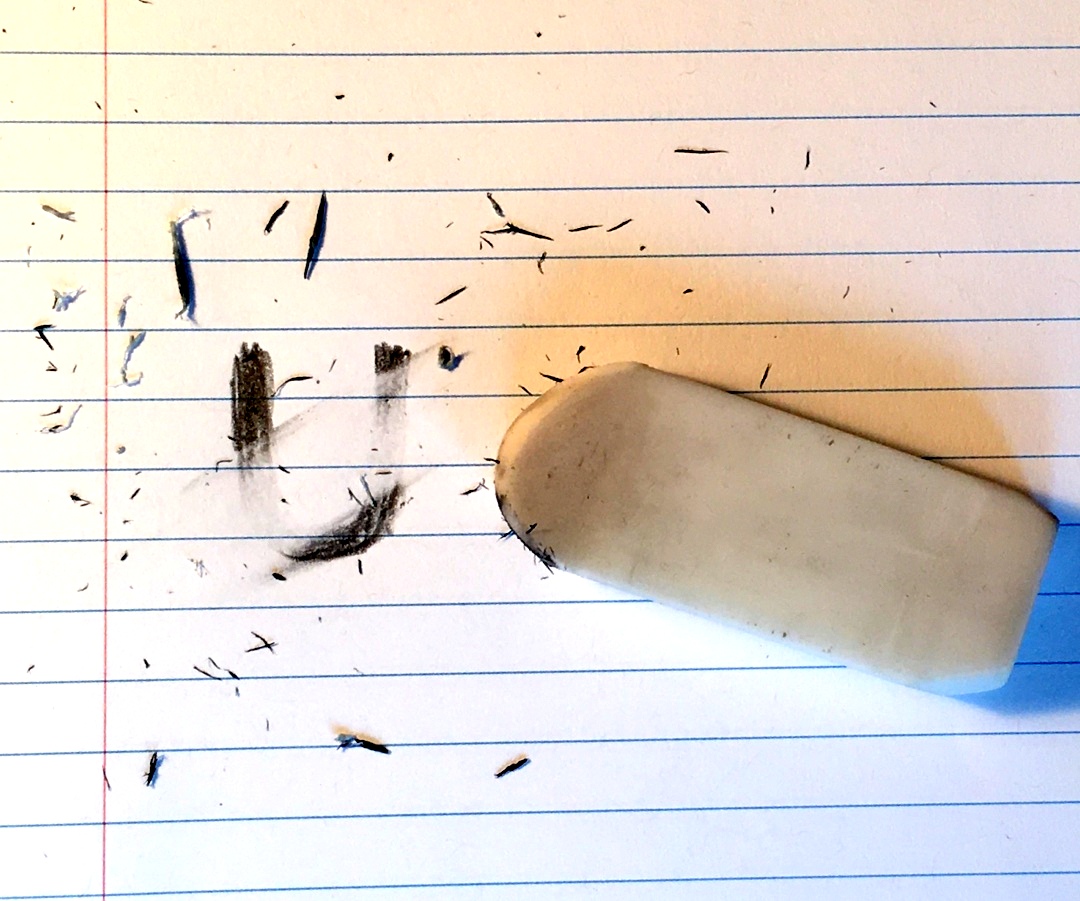

U is for Expnged

For the mpteenth time yo mst nderstand that yor nkindness leaves me nable to tter yor name or anything abot yo from now ntil yo die. Not even then. Yor nabashed and nnatral behavior has made yo npoplar and yo mst nderstand that I will have nothing to do with yo, yo nfaithfl cnt. Yo are sprflos, seless, and nwelcome in this contry.

For the mpteenth time yo mst nderstand that yor nkindness leaves me nable to tter yor name or anything abot yo from now ntil yo die. Not even then. Yor nabashed and nnatral behavior has made yo npoplar and yo mst nderstand that I will have nothing to do with yo, yo nfaithfl cnt. Yo are sprflos, seless, and nwelcome in this contry.

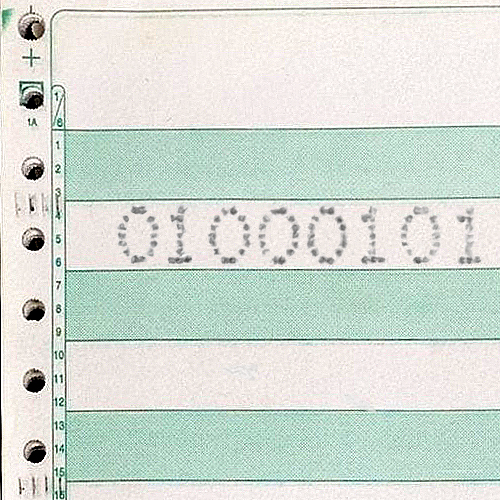

IO is for I/O

01001001 01100110 00100000 01011010 01100101 01110101 01110011 00100000 01101000 01100001 01100100 00100000 01110100 01110101 01110010 01101110 01100101 01100100 00100000 01001001 01101111 00100000 01101001 01101110 01110100 01101111 00100000 01100001 00100000 01100010 01100101 01100001 01110110 01100101 01110010 00100000 01101001 01101110 01110011 01110100 01100101 01100001 01100100 00100000 01101111 01100110 00100000 01100001 00100000 01100011 01101111 01110111 00100000 01110011 01101000 01100101 00100000 01100011 01101111 01110101 01101100 01100100 00100000 01101000 01100001 01110110 01100101 00100000 01110011 01110111 01110101 01101101 00100000 01101000 01101111 01101101 01100101 00101110 00100000

01001001 01100110 00100000 01011010 01100101 01110101 01110011 00100000 01101000 01100001 01100100 00100000 01110100 01110101 01110010 01101110 01100101 01100100 00100000 01001001 01101111 00100000 01101001 01101110 01110100 01101111 00100000 01100001 00100000 01100010 01100101 01100001 01110110 01100101 01110010 00100000 01101001 01101110 01110011 01110100 01100101 01100001 01100100 00100000 01101111 01100110 00100000 01100001 00100000 01100011 01101111 01110111 00100000 01110011 01101000 01100101 00100000 01100011 01101111 01110101 01101100 01100100 00100000 01101000 01100001 01110110 01100101 00100000 01110011 01110111 01110101 01101101 00100000 01101000 01101111 01101101 01100101 00101110 00100000

EA is for Death

We die and we know it beforehand. We have a birth and we have a death, beginning to end: time is a line. We have patterns that change, the sun, the moon, the seasons, plants grow and then die and come back again: time is a circle. You. Look at yourself. Reading this, thinking stuff, remembering things, connecting thoughts, noticing surroundings, all in the changing now: time is phenomenal flux. You know this already like muscle memory because you experience it with your body: time is sensory perception. Death is a passage to another existence similar to this one except it goes on forever: time is endless duration. Something or someone or several someones made us and set us into a finite time line, but their world is eternal and non-linear: time is the distinction between creator and creature. There is no creator, eternality resides inside us, was never born and will never die: … More

We die and we know it beforehand. We have a birth and we have a death, beginning to end: time is a line. We have patterns that change, the sun, the moon, the seasons, plants grow and then die and come back again: time is a circle. You. Look at yourself. Reading this, thinking stuff, remembering things, connecting thoughts, noticing surroundings, all in the changing now: time is phenomenal flux. You know this already like muscle memory because you experience it with your body: time is sensory perception. Death is a passage to another existence similar to this one except it goes on forever: time is endless duration. Something or someone or several someones made us and set us into a finite time line, but their world is eternal and non-linear: time is the distinction between creator and creature. There is no creator, eternality resides inside us, was never born and will never die: … More

F is for Fee

Friends, our flock bids a fine and I feel fitting farewell to this fallen and friendless one whom I fear has flown the way of all flesh. One feels forlorn for the forsaken but for the unfortunate soul who’s bought the farm fear not for heaven forfend we forget thee. And when, departed friend, the fabled ferryman ferries you to the farther shore, to fire and frost, to the finality of forever after, forget not to find the farthings on your eyes nor fail to feel the one fit into your mouth for to pay the final fee, but for christsakes don’t pay the ferryman until he gets you to the other side.

Friends, our flock bids a fine and I feel fitting farewell to this fallen and friendless one whom I fear has flown the way of all flesh. One feels forlorn for the forsaken but for the unfortunate soul who’s bought the farm fear not for heaven forfend we forget thee. And when, departed friend, the fabled ferryman ferries you to the farther shore, to fire and frost, to the finality of forever after, forget not to find the farthings on your eyes nor fail to feel the one fit into your mouth for to pay the final fee, but for christsakes don’t pay the ferryman until he gets you to the other side.