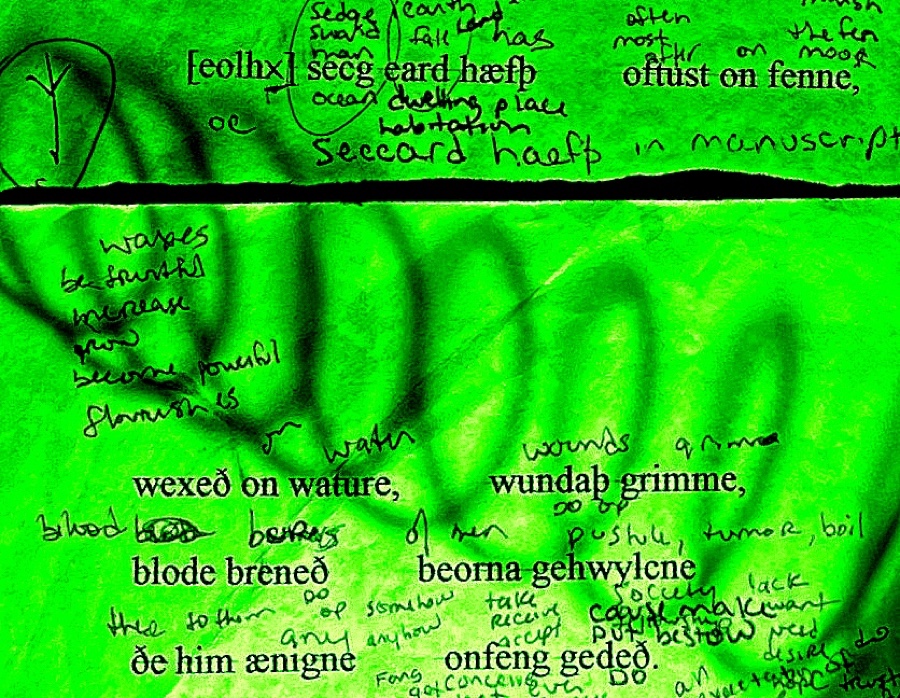

This is a stanza about a plant; this is clear from the context and from the word secg, which means a sedge or reed. It also means a person, poetically, and a sword. In Beowulf it is a sword: ac wit on niht sculon secge ofersittan, gif he gesecean dear wig ofer wæpen (but we two are obliged to abstain from the sword in the night, if he dare seek battle without a weapon.) I translate secg as sword to enhance the riddling nature of the stanza. Of all the plants, a sharp sedge is the most sword like. It’s got edges like razors and will cut you just like that. This one in particular will give you grim wounds, with burning bloody blisters. Stay away, don’t grab hold of it. Like the thorn, this plant wants you to bleed.

This is a stanza about a plant; this is clear from the context and from the word secg, which means a sedge or reed. It also means a person, poetically, and a sword. In Beowulf it is a sword: ac wit on niht sculon secge ofersittan, gif he gesecean dear wig ofer wæpen (but we two are obliged to abstain from the sword in the night, if he dare seek battle without a weapon.) I translate secg as sword to enhance the riddling nature of the stanza. Of all the plants, a sharp sedge is the most sword like. It’s got edges like razors and will cut you just like that. This one in particular will give you grim wounds, with burning bloody blisters. Stay away, don’t grab hold of it. Like the thorn, this plant wants you to bleed.

This sedge lives in the fen. The stanza says fenne, a fen is a fen and I could have kept it as a perfectly fine word for a swampy place, but I use the word marsh because it alliterates with the word most. Alliteration is also the reason I translated gehwylcne, a whelk, as pustule. Alliteration is the first thing to go in Old English translation; it’s always important to preserve it when possible.

This plant was unpleasant. Why ever would anybody want to gather them? Why was this plant so important it gets the center position in the Rune Poem? For one, it might have been used for roof thatching. They would be pretty durable for that. Waterproof. Another clue might be found in the many Old English manuscripts we have containing word glossaries. In them under the words eloxsecg, eolugsecg, ilugsegg, ilugseg, is the definition papiluus: papyrus. Perhaps this sedge was used for paper making? It would have been brittle paper that crumbles when dry, falls apart when wet, paper easily eaten by mold and bookworms, paper that oxidizes too quickly when touched by iron gall ink, paper that burns, paper that has not lasted the centuries, maybe not even a single century: words, so many of them, speaking what we’ll never know, gone.

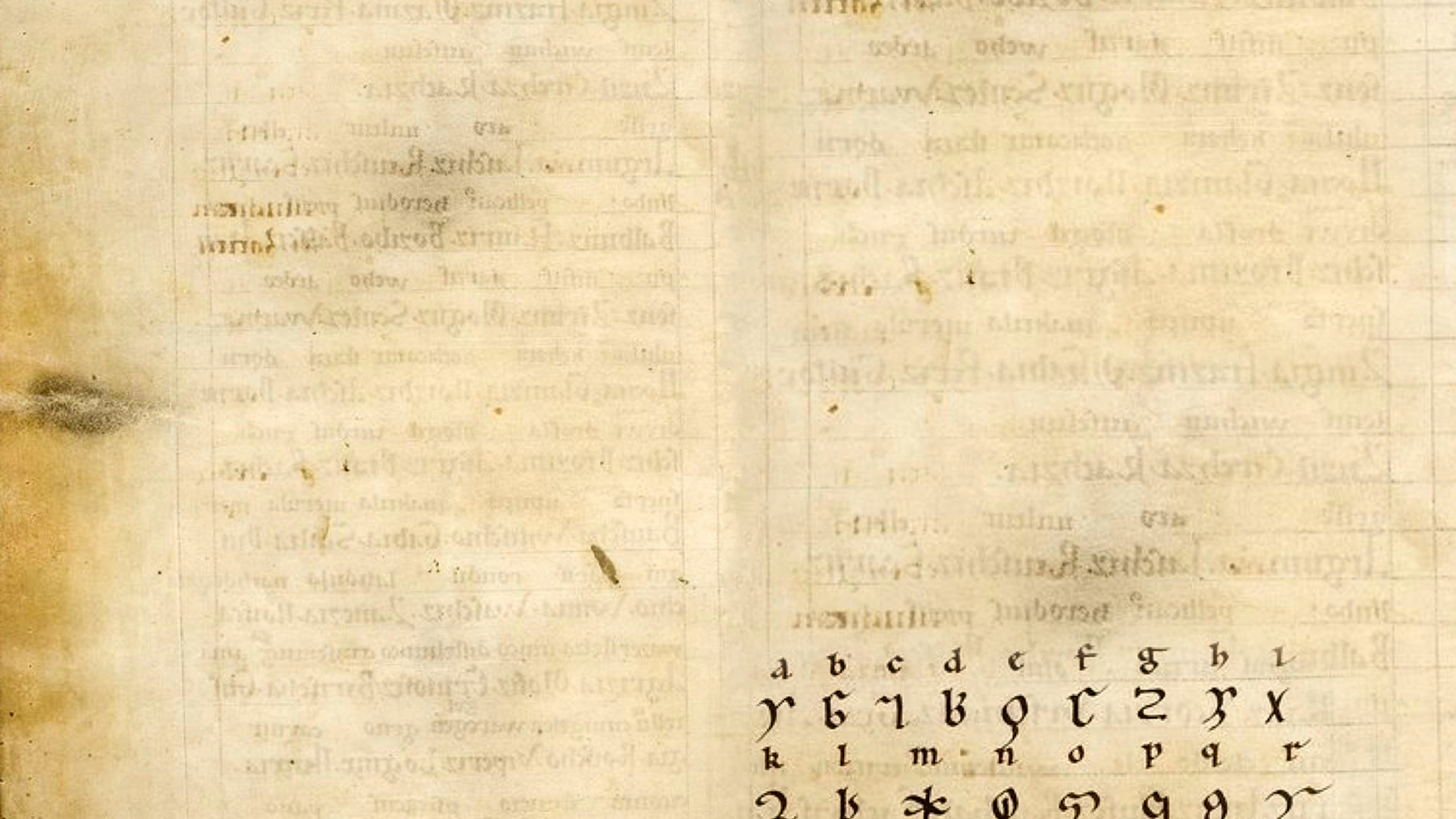

All this is if this secg is the correct word. The copy we have of the burned Rune Poem manuscript doesn’t say secg eard, meaning sedge and dwelling place, it says seccard, meaning nothing. Seccard is not a word. Why does the copy say seccard? This word sits just after the Peorþ stanza, with its missing word, so perhaps the manuscript page had problems here. Or the scribe did a poor job copying both stanzas? Most translators want that second C in seccard to be an E, which looks similar to C with blurred vision or in poor lighting, but gives more options: eard (dwelling place) geard (a yard, hedge fence, staff). These things make sense, especially eard. The stanza could be talking about a home in a fen. The poem has spoken of other home locations in other stanzas like the ones for Beaver and Aurochs, so we are on familiar damp ground here. That leaves sec at the beginning of seccard to mean something. Secan means to seek and secgan means to speak, both are verbs, but by word placement this seccard is probably a noun; verbs often come dead last in an Old English sentence. Secge is a noun meaning speech, like what you might write on a piece of brittle paper, but from the context the likeliest word it might be is probably not secge, it’s secg, sedge, a sword-like sedge, though speech can burn you into blisters if you let it. Perhaps some sort of pun was intended? It wouldn’t be the first time.