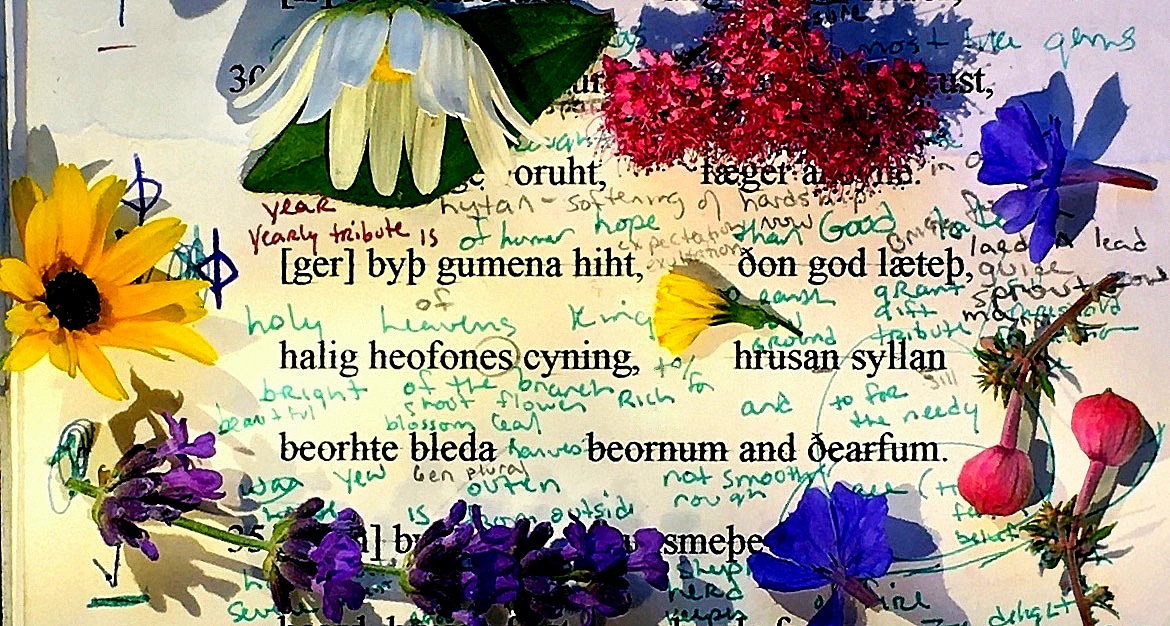

This stanza is about time. Some see it as a specific time, like harvest when the bright bleda (fruits) mentioned are ready for eating. Others translate this as springtime, when bleda, which also means blossoms and green shoots, appear on plants. Which bleda do we want? In Old English poetry, multiple meanings apply. What kind of temporality were the people of the Rune Poem working with? We can look closely anywhere in Old English and see it, but we ought to pay attention here in the Ger stanza to find out how they managed their solar time reckoning at least. The moon is another matter.

This stanza is about time. Some see it as a specific time, like harvest when the bright bleda (fruits) mentioned are ready for eating. Others translate this as springtime, when bleda, which also means blossoms and green shoots, appear on plants. Which bleda do we want? In Old English poetry, multiple meanings apply. What kind of temporality were the people of the Rune Poem working with? We can look closely anywhere in Old English and see it, but we ought to pay attention here in the Ger stanza to find out how they managed their solar time reckoning at least. The moon is another matter.

The name of this rune is ger, year. What is a year? A cycling of the seasons. There is a time when the sun is with us a lot, and then another time after that when it is not, and then when it is again. Time is a circle. Time is a cycle. When the sun is gone you miss it, you sit in the frost, watch your supplies from the growing season dwindle and would desperately like to know when the sun will again increase its time with us each day. Time is endless duration. Time has a start. When does it start? Watch the sun and see. It rises and sets in a slightly different spot on the horizon every day, you can mark its shifting position, farther away or closer to a middle. Time is a line. Time is an arc.

Each end of the sun’s road, when it turns back the other way, is a solstice. When the sun reaches the cold end of one and starts moving back, we can call this a new year, many do as it is when all the life starts back up again. People of a different stripe like to observe the middle, the equinox where as much road stands before the sun as behind. Now look at the Rune Poem. The stanzas line up in thematic pairs from the ends to the middle. By pairing the Ger stanza with Beorc, Birch, the tree of earliest spring which puts out buds before the rest, and closest in timing to the middle of the sun’s road, the Rune Poem gives a clue that it was not the ends but the middle of the Sun’s path of life they thought of as a starting point to the year. The middle does make an excellent beginning. The sun gets to the middle of its path of life twice a year: the spring and the fall equinoxes, and there is no doubt which of these two middle moments the Ger stanza is talking about with its fruits and flowers. Time starts over in the spring.

Solar time reckoning wasn’t the main focus here in the Rune Poem, though, they did keep close track of it and of the moon, which rides its own path back and forth to a middle. But don’t forget what really counts on a more personal survival level to this culture’s time reckoning is the plants. The plants are food, and food for food. So when they are gone, we need to know when are they coming back. Because the frost came and killed everything and now we find out how well our harvest went. And how well everything can keep. When does the new year come and we can get the planting started? When you can see green growth on the branches. This is an important moment, it means hiht, hope and exultation, but also trust and expectation. That might be all you have left by the end of February start of March. Hytan means a softening of hardship. New growth says that the lean months are coming to an end and you can look forward to fruits on trees, crops growing, fodder for the livestock you’ve been able to hang onto and feed through the winter. Abundance is coming back to the world, it is a new ger.

How does it happen? God, that’s how. There are plenty of gods in the Rune Poem, the one in this stanza appears to be more Christian than the others by description: halig heofones cyning, the holy king of heaven. This is a usual description of the chief Christian deity. Of the gods known to the people of the Rune Poem, gods are not often kings. Christianity was a minor one of the many religions brought to Britain by the Romans, and it didn’t really take until the 6th and 7th centuries, roughly around the time the Rune Poem was written down. There was overlap, I’m saying, and In the Rune Poem, this Christian sounding holy king of heaven is what somebody of this culture might expect of a god who also holds the job of cyning.

Look at what this king of heaven does, look at the word syllan: the king gives. I don’t need to tell you how important giving is to the culture of the Rune Poem, in all the multiple ways it can happen. It is everything. It means everything, your own worth and honor as a person depends upon what you can give. Holding onto something is a dishonor even to whatever it is you are keeping. Who do you give to? Everybody must give to the ðearfum, the needy, and everybody must give to people they receive from, especially the beornum: the wealthy people who are the heads of your family, the chief, the cyning, and the gods, who all give what they have to you. This is not a two way street, it’s a roundabout. Giving is a paying of tribute to others and people trust in it. Syllan, or sellan (the letter Y is shifty) is a word that means entrust, and it means giving what you are bound to give, the gods being no exception to the obligation. Everybody gives to them too, and they must give back. The god in the Ger stanza, the king even of the kings will do what kings do and give more than anybody else, it is everybody’s hope and expectation. They have more they give more. þæt wæs god cyning!

Who is this king of heaven, this cyning god? It seems this king is a fertility deity caught by the Ger stanza in the act of giving. Look at how it happens: ðon god læteþ, lets, as in allows to happen, but with a flavor of agency because læteþ means to lead, guide, conduct, bring forth, sprout, grow, spread, and marry. These are the actions of the spring. Green buds appear in the brown, they sprout and spread; it is an ushering in of newness, very welcome after the ice. The new life in spring doesn’t just happen, it is a tribute paid by a generous king, somebody who might also serve their own king in another nested level of scale. Perhaps it’s kings all the way down?

Heaven’s king does not pay tribute to us, not directly, the Rune Poem makes this clear. It’s syllan hrusan to whom the god king gives: to the earth, the soil, the material ground. Then it is the earth who pays the tribute on to us, all of us, the rich and the needy, with gifts of beorhte bleda, bright blossoms that turn into fruits, with growing plants we can harvest in their time and eat through the winter and feed to our animals while we wait, with hope and expectation, to be entrusted again with another new year.