Os means God, non specified, though this stanza might be talking about a specific one. There are other specific gods in the Rune Poem. Tiw is here. So is Ing. We don’t know much about Ing. We don’t know much about any of the Gods the rune carvers were listening to. We do know the Nordic ones thanks largely to the thirteenth century Icelandic poet Snorri Sturluson, who compiled folk traditions into stories for a Norse king who liked his entertainment. Britain also being a North Sea culture, there was plenty of overlap. There’s not much written about the deities in Old English, though. Most everybody doing the writing was Christian, so. They had an agenda. These Christians preferred a reduction of the Gods down to a singularity, a point encompassing all other points, so the extra Gods they’d encounter tended to disappear.

Os means God, non specified, though this stanza might be talking about a specific one. There are other specific gods in the Rune Poem. Tiw is here. So is Ing. We don’t know much about Ing. We don’t know much about any of the Gods the rune carvers were listening to. We do know the Nordic ones thanks largely to the thirteenth century Icelandic poet Snorri Sturluson, who compiled folk traditions into stories for a Norse king who liked his entertainment. Britain also being a North Sea culture, there was plenty of overlap. There’s not much written about the deities in Old English, though. Most everybody doing the writing was Christian, so. They had an agenda. These Christians preferred a reduction of the Gods down to a singularity, a point encompassing all other points, so the extra Gods they’d encounter tended to disappear.

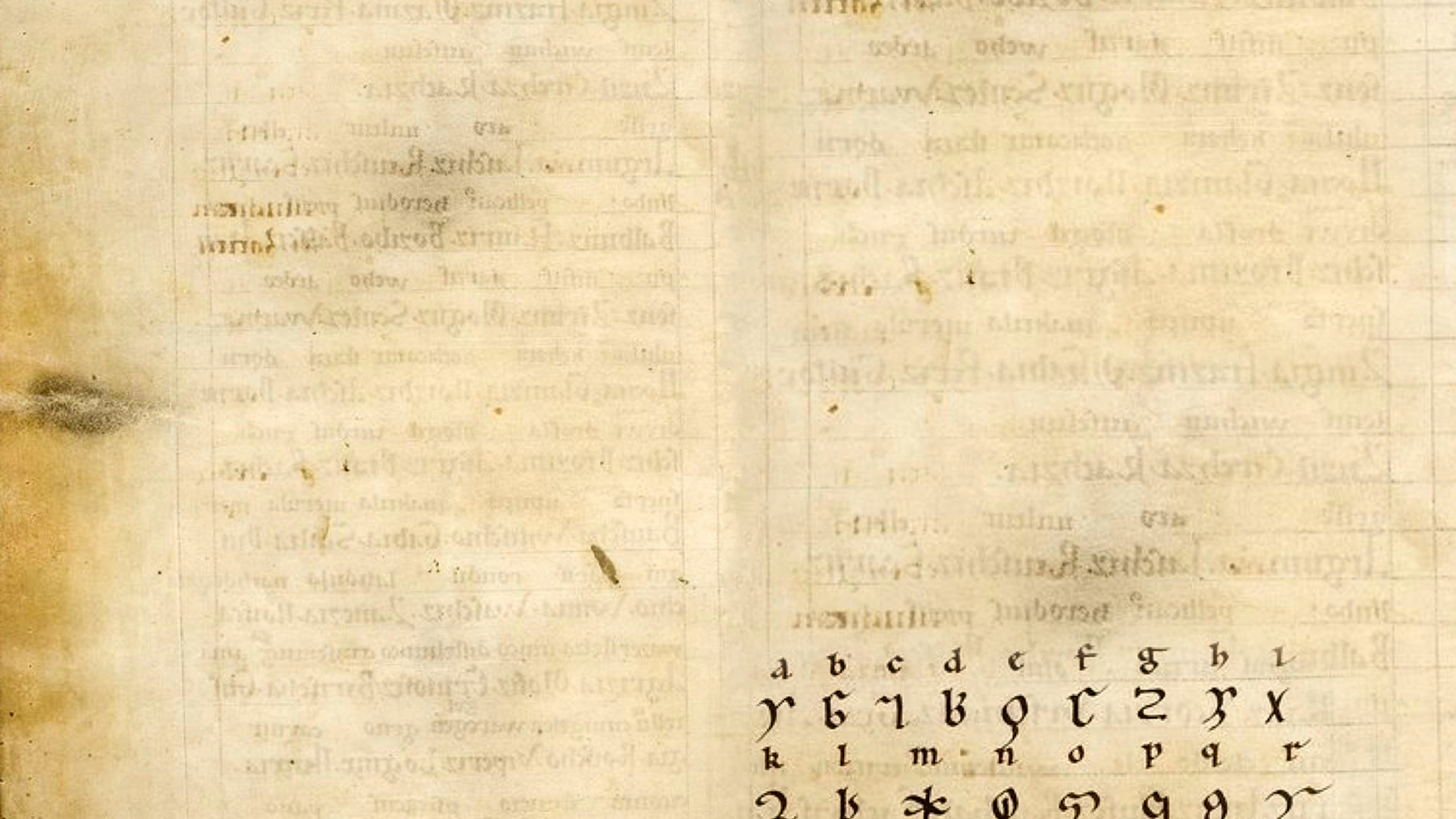

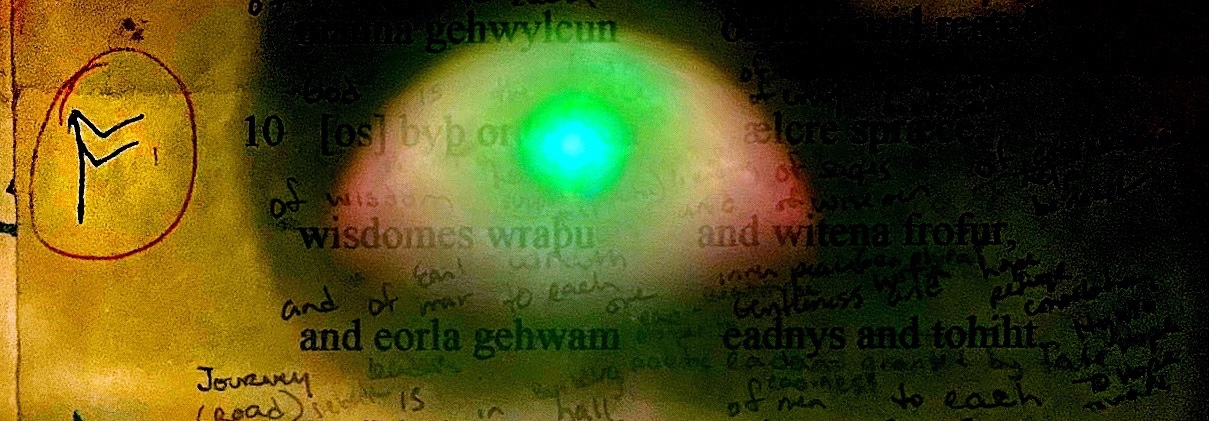

The word Os was disappearing too, by the time somebody wrote down the Rune Poem, but it is also the Latin word for mouth so it hung on in that capacity by the skin of its teeth. People sometimes translate this rune as mouth instead of God. For a long time I called it God Mouth, because Os byþ ordfruma ælcre spræce, Os is the source of all speech. Ordfruma also means author or creator, like a deity, so if this is a God this is one who presides over wisdom as well as speech. Eloquence and wisdom. Who does that sound like, besides so many of them? To the Roman historian Tacitus who traveled in Germania and reported back, this god sounded like Mercury. That’s what he called him, Mercury. But what specific North Sea coast poet deity who presided over language does this also sound like? Odin. It sounds like Odin, with the letter O, which is the letter for this rune. Throw in an ash tree, and we’ve got Odin sacrificing himself to himself on the great ash Yggdrasil so he could learn rune casting. Oh wait! We’ve got an ash tree right here.

But that story, Odin hanging from his own spear in the great world ash tree was written down many centuries later than this deity’s time. What is this God’s story? We don’t know. Is this the same God? Who knows. We know he wasn’t called Odin in Britain, he was Woden. I see what you’re thinking, I know that look on your face. Odin Woden, Odin with a W. Close enough. But is it? Maybe, but we have no way of knowing. They were likely related, but even a set of identical twins can have vastly different personalities. We know Woden was the big God of his pantheon, like Odin, but all we have written down in Old English is his name at the start of a bunch of genealogies. Everybody liked tracing themselves back to Woden. He was all their daddies.

As the likely Os of this stanza, Woden might have been a bit temperamental. Look at the word wrauþu. With the U on the end it is a poetic word for support and help, but with a flavor of being the point of origin of something helpful, the instigator. Without the U it’s wrath. Or wroth. It’s a pun either way, Old English loves a pun, so Woden might be supportive and helpful to his people, but don’t piss him off. Just don’t.

Not to worry, though, in this stanza he’s the bringer of eadnys and tohiht. Hiht. Height. Tohiht, toward the heights. This means hope, Woden brings hope and prosperity. Ead means prosperity, but with a flavor of how it feels when prosperity is brought by fate. Eadnys. The state of ead-ness. It’s the word you want when you mean gentleness, inner peace. Beatitude. Woden brings ease and hope. No wonder everybody wants to be his relative.