The Rune poem names two gods: Tiw and Ing. Three if you count Os which means god and describes Odin. If we set aside all the sacred trees, and we shouldn’t, we still have one more god mention: the holy king of heaven in the Year stanza, who must be the Christian god, unnamed. This Christian incursion into a poem full of non Christian deities, two named right out loud in answer to their stanza riddles, sometimes poses a different kind of riddle for Christian readers and translators. Perhaps duty bound to exalt their own, they often determine this is a Christian poem written by a Christian poet who would never allow heaven’s king to share an equal stage with other gods. This was a preference undoubtedly popular amongst Christian poets writing in Old English back in the day, so I can see the impulse. But I am here to encourage the heaven king’s followers that when discussing Tiw, please don’t feel you have to emphasize the astronomical elements and downplay the deity. You can call Ing a god, not just a hero. Odin is very much here. And the trees are gods too. Tiw, Odin, the king of heaven, and a whole grove of trees, were fine with each other. Neighborly. They have no problem sharing a poem and a culture.

The Rune poem names two gods: Tiw and Ing. Three if you count Os which means god and describes Odin. If we set aside all the sacred trees, and we shouldn’t, we still have one more god mention: the holy king of heaven in the Year stanza, who must be the Christian god, unnamed. This Christian incursion into a poem full of non Christian deities, two named right out loud in answer to their stanza riddles, sometimes poses a different kind of riddle for Christian readers and translators. Perhaps duty bound to exalt their own, they often determine this is a Christian poem written by a Christian poet who would never allow heaven’s king to share an equal stage with other gods. This was a preference undoubtedly popular amongst Christian poets writing in Old English back in the day, so I can see the impulse. But I am here to encourage the heaven king’s followers that when discussing Tiw, please don’t feel you have to emphasize the astronomical elements and downplay the deity. You can call Ing a god, not just a hero. Odin is very much here. And the trees are gods too. Tiw, Odin, the king of heaven, and a whole grove of trees, were fine with each other. Neighborly. They have no problem sharing a poem and a culture.

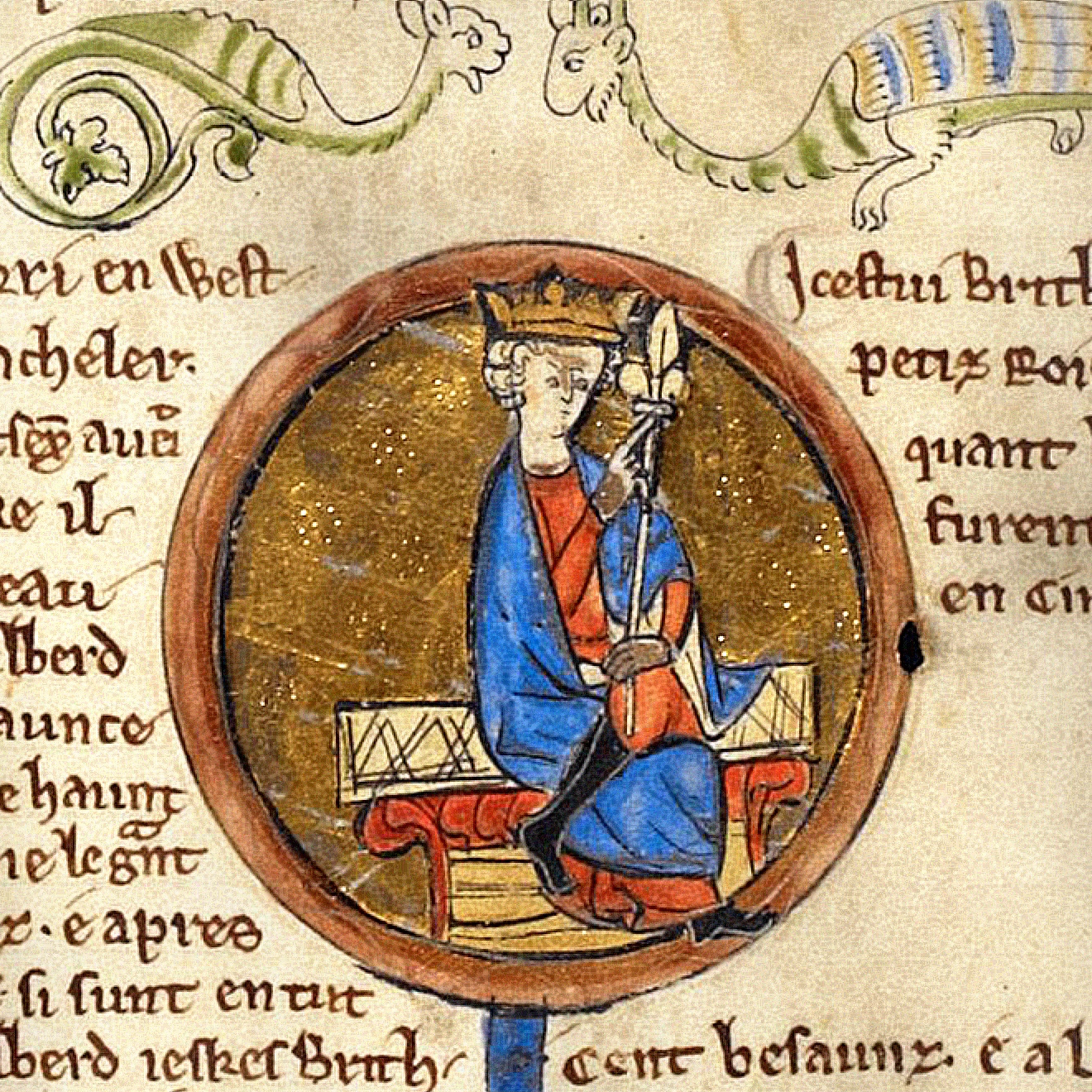

The Rune Poem gods, and many many others, had been mixing in Britain for a long time: as long as the Romans were around. Being a part of such a massive empire meant that people from all over were circulating, especially the soldiers and merchants who came from everywhere and brought their home deities with them to live side by side with everybody else’s. Christianity was not one of the a big religions when piled up together with all the others, but the king of heaven was not unheard of. He mixed right in with everybody else, and it makes sense he’d be found in the Rune Poem in a neighboring pair with Tiw’s and located right under Odin when arranged into their traditional rows of eight: Odin stood above the heaven king in importance when the Rune Poem was arranged. Perhaps this Christian king god appears in the stanza about spring because of the supreme importance of Easter in his ritual calendar? Tiw was a spring diety too as this was the start of the war season. Nobody wants to go to war in winter.

After the Romans stopped governing Britain, the people stayed polytheistic. We don’t have much to go on during this time as far as a written record, which goes a bit dark for what seems like ages. We know that the bones and grave goods from this period maintain a cultural mix. We also know that the king of heaven became fashionable at this time amongst the elite in Britain, mostly as an import from the Franks to the south who were Christian and had the best jewels and the good wine. The rich in Britain were getting richer and they wanted to do as the Franks did.

Anything Roman had come to symbolize the ease and opulence of the long gone Roman days, which appealed to the wealthy as well. When Pope Gregory sent a mission from Rome to convert King Æðelberht’s city of Canterbury in 596, the Romans who arrived had an easy time being accepted by the fashionable. Well, they did eventually. When about twenty priests and the future Saint Augustine of Canterbury first landed in Kent, they must have had an immediate shock of some kind because Augustine turned right around and went straight back to Rome to ask Pope Gregory if he was sure they should be doing this. He was sure. The queen in Kent was Bertha, a Christian Frank whose god was already living right next to King Æðelberht’s and they were fine with each other. Æðelberht gave Augustine a house within the walls of Canterbury, and allowed the priests to recruit as many followers as they liked so long as they didn’t make a nuisance of themselves. They succeeded for a time, thanks to Æðelberht’s tolerance and ultimate conversion. What the King does everybody else wants to do too, this is how fashion works, at least until there’s a next king.

The next king was Æðelberht’s son Eadbald who “abandoned his baptismal faith and lived by heathen customs, so that he had his father’s widow as his wife,” according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle’s entry for the year 616. The chronicle entries for these years were written long after the fact and I suspect Eadbald’s people would have put it differently. Eadbald’s mother Bertha had died before her husband King Æðelberht, who must have married a non-Christian woman after that. Marrying your stepmother was not allowed in the Christian Church, and despite later converting to Christianity and dumping his step mother for Ymme, a Frankish Christian woman, King Eadbald likely kept the old ways going in tandem with the new, just as his father King Æðelberht had done. Just as King Rædwald of East Anglia did, who converted to Christianity on a trip to Canterbury to visit King Æthelberht, and as a souvenir set up an altar to the heaven king within his shrine for his other gods. This is the same King Rædwald who might have been buried at Sutton Hoo, which is about as non Christian a burial as it gets for somebody who converted to Christianity. Christian burials were sparse affairs and his is a whole buried ship for Christssakes, crammed with stuff.

After Eadbald died in 640, the chronicles say his son, the new King Eorcenberth “demolished all the idols in his kingdom and was he first of the English kings to establish the Easter fast.” It’s a big deal to convince the people not to eat meat at that lean end of winter when food stores are running out and people are hungriest. The population must have been more receptive of Christianity by that time. Lenten fasting allows fish, and it did help that the priests got creative about what qualified as one.

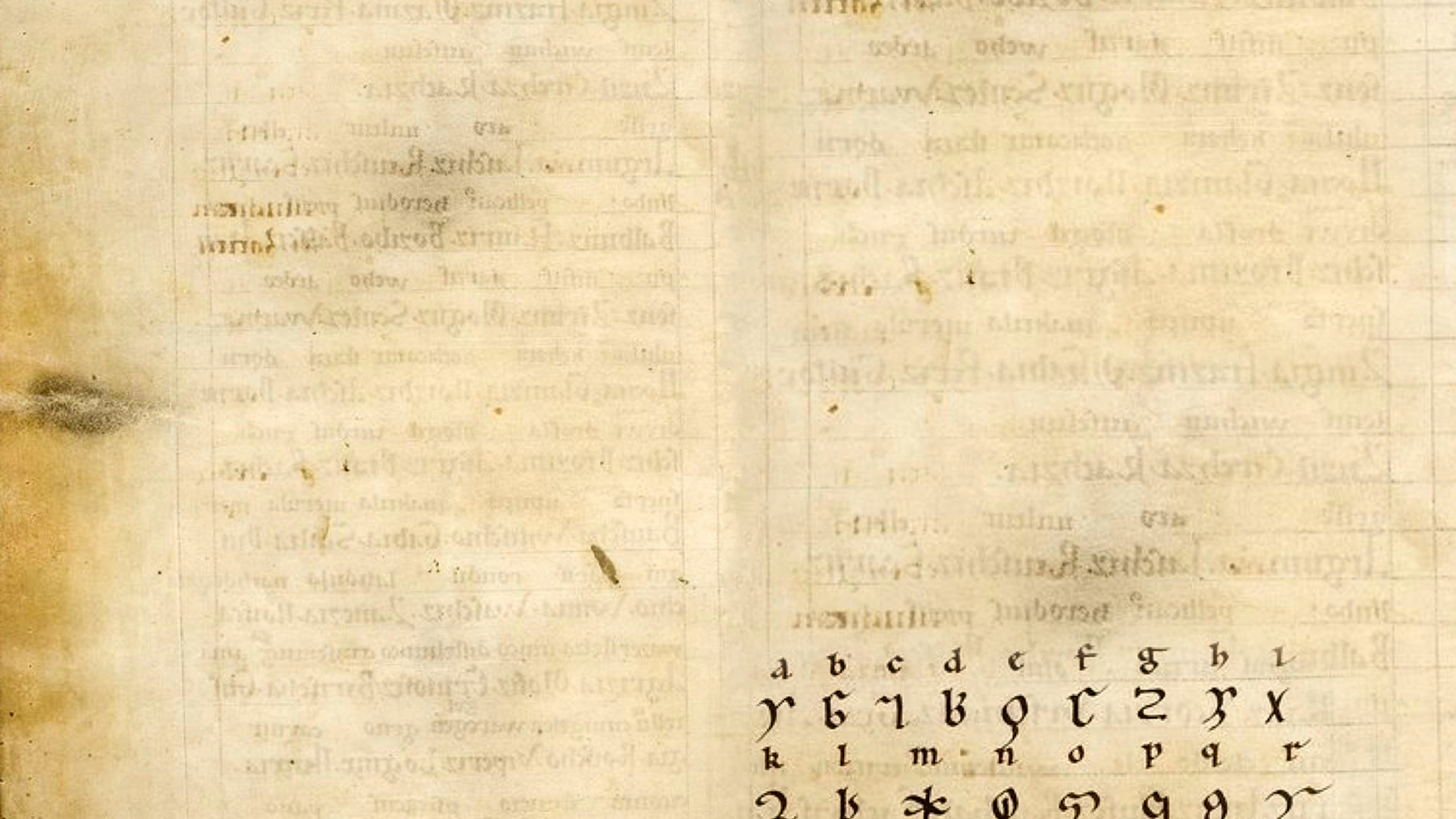

Christianity waxed and waned generationally amongst the elite, all over Britain. For the rest of the people changes were less abrupt, less pronounced, and just as many people do today, the people in Britain mixed their religions together. A place organized into kingdoms could accept a king in heaven, so the incorporation of a king god into the pantheon was not a difficult concept, and for a long time if you were a worshiper of Tiw, perhaps you are a soldier who carves Tiw’s rune onto your weapon, you might also appreciate a buckle or a brooch with a cross on it. Your grave might be marked by a stone bearing both a cross and your name spelled in runes to provide magical protection to your bones. Although strictly Christian burials meant no grave goods, yours might contain a decorative cross on your breast and a side of beef on your belly. You may have a rune carved knife at your side, and your people might have turned your head eastward toward Jerusalem and in the direction of the rising of Tiw’s constellation on a journey over the obscurity of night.