Old English poetry was performed, probably sung, for purposes beyond mere entertainment. The Germanic tribes Tacitus visited at the end of the first century would prep for battle by barding, which he called “a peculiar kind of verse” sung to stimulate their courage and to divine the outcome of the coming fight through the quality of the sound itself. Tacitus tells us about these peculiar verses almost immediately in his report back to the empire, so you know it was impressive. It would be. Imagine it: he says the people would put their battle shields to their mouths, perhaps in them, and sing. A shield as a musical instrument. Their favorite sounds were “a harsh piercing note and a broken roar,” which “does not seem so much an articulate song, as the wild chorus of valor.” What were the words? Were they the names of the gods? An appeal for their protection? A share in their courage? Hwat? Whatever it was, it was loud, and it was important. They could tell the future from what they could hear, barding before battle, so it better sound like the right future. The gods are listening, and talking, so make it count. Think of what the experience of standing amidst all that resonance would be, words vibrating into your core, amplified by the shields and the adrenaline. Imagine an army coming at you sounding like that. Poetry as augury and weapon. Terrifying.

Old English poetry was performed, probably sung, for purposes beyond mere entertainment. The Germanic tribes Tacitus visited at the end of the first century would prep for battle by barding, which he called “a peculiar kind of verse” sung to stimulate their courage and to divine the outcome of the coming fight through the quality of the sound itself. Tacitus tells us about these peculiar verses almost immediately in his report back to the empire, so you know it was impressive. It would be. Imagine it: he says the people would put their battle shields to their mouths, perhaps in them, and sing. A shield as a musical instrument. Their favorite sounds were “a harsh piercing note and a broken roar,” which “does not seem so much an articulate song, as the wild chorus of valor.” What were the words? Were they the names of the gods? An appeal for their protection? A share in their courage? Hwat? Whatever it was, it was loud, and it was important. They could tell the future from what they could hear, barding before battle, so it better sound like the right future. The gods are listening, and talking, so make it count. Think of what the experience of standing amidst all that resonance would be, words vibrating into your core, amplified by the shields and the adrenaline. Imagine an army coming at you sounding like that. Poetry as augury and weapon. Terrifying.

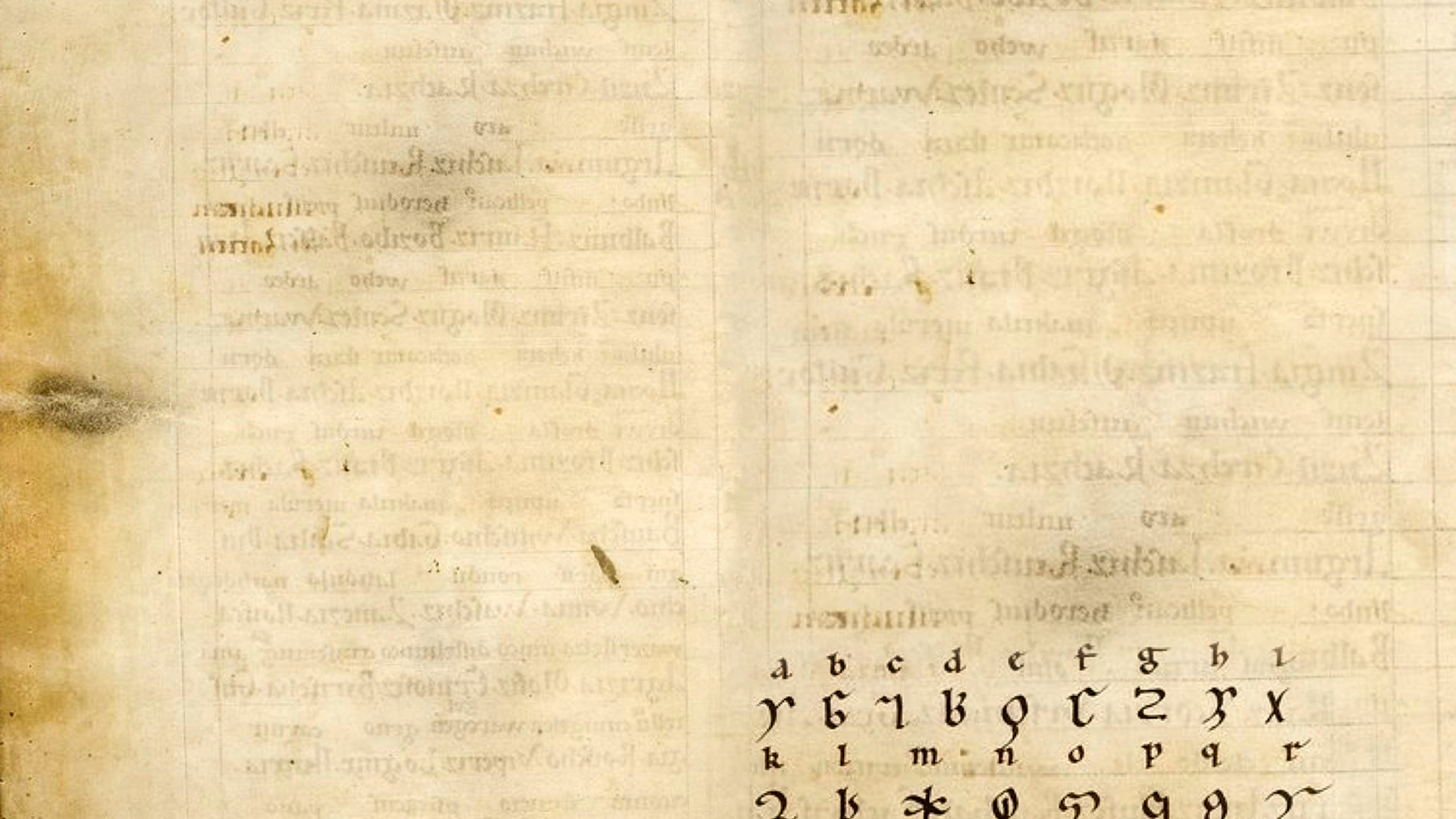

The Rune Poem is also poetry as augury, and I expect it was sung in plenty of terrifying circumstance. I expect it was sung because most Old English poems were songs, and because they ordered the Rune Poem into groups of eight like octaves: eight notes arranged by their frequencies, which you can feel very particularly for yourself whilst barding with a shield in your mouth. An octave is eight notes because when a sound’s frequency doubles, it takes eight notes to get there. Middle C vibrates at 261.6hz, tenor C’s vibration doubles that rate: 523.2hz, and double again to Soprano C and again to double high C. You can divide going the other way too, it’s Cs all the way down, and all around the world as well, plenty of cultures knew that music is the voice of mathematics.

The Rune Poem is arranged into three octaves, as many as a single person’s voice can reach. The octaves are named after the gods Freyr/Freya, Tiw, and Hægl who gets an octave despite never having existed. After the three octaves, five vowels are tacked on. They are the sounds for runes not as old as the originals which were already old when the Rune Poem was written down. We need these extra vowels, they are the slipperiest letters and have a way of shifting into new sounds that need to be represented by new letters all the time. I wonder what their notes were, the new vowels, were they half notes like sharps and flats? What did each rune sound like, and were they sung together as chords? What about the pairs that form when you line them up in a string and dangle both ends from the middle? What would that sound like? What stories did that poetry sing? What meanings could you make by sounding runes together, like human and need, or the sea and the sun? Could a person transmit a comprehensible message just by humming notes? Was a person’s name also a melody? The runes for god and for human are the same note two octaves apart, separated by the new year in the middle: linear human temporality as defined by the calendar cycle has always divided us from understanding our gods’ eternality. That’s the oldest song ever, and what does it sound like? Somebody ought to compose it and write it down this time so people will remember, so it is not just gone forever the second the last of its singers close their mouths.