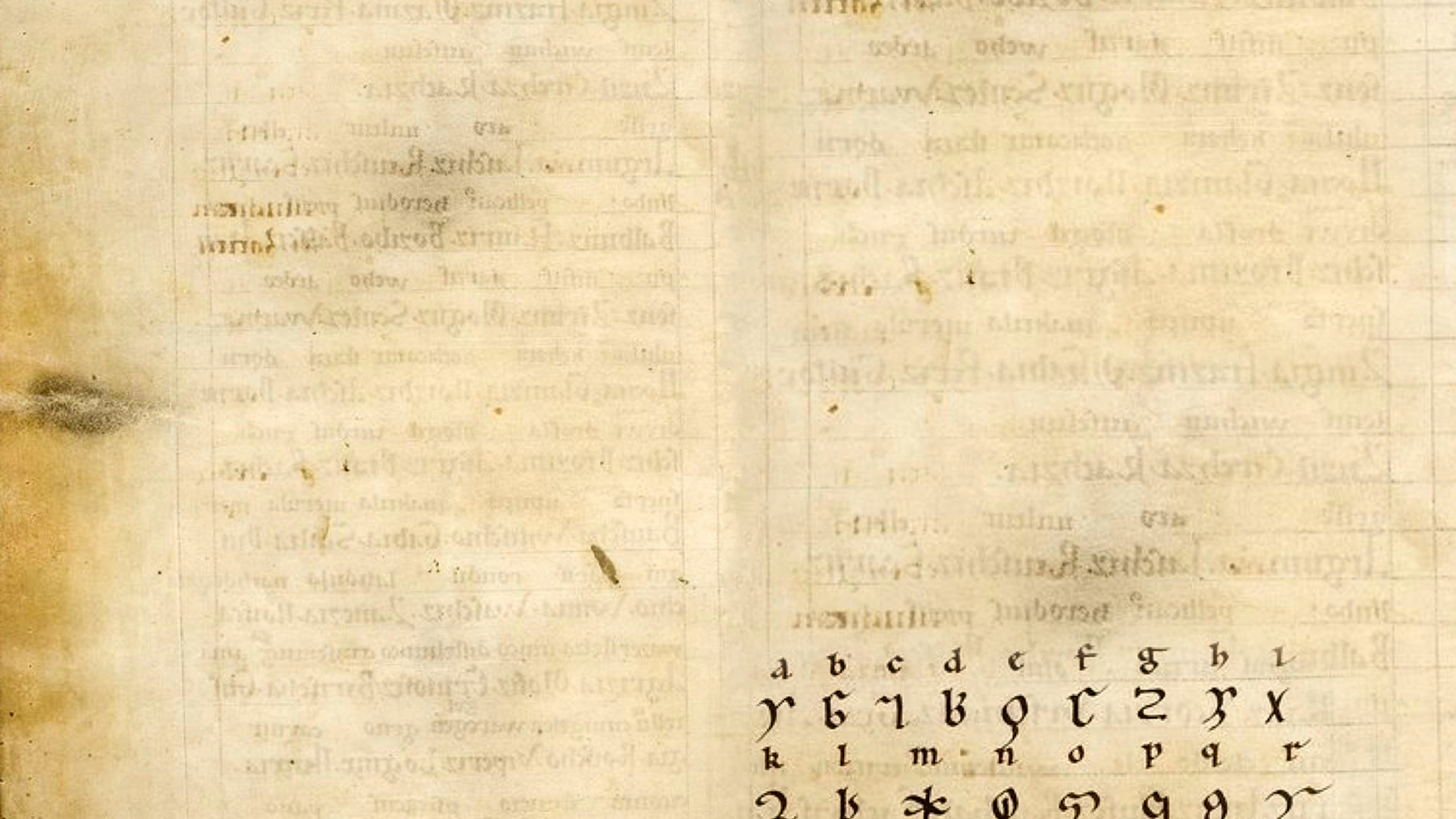

Archaeologists in their digging and dating trace the oldest runic alphabet back to the late second century. The oldest rune carvings are often of the alphabet itself, carved in order. They’ve found runes etched into durable things like rock, metal, bone, but sometimes the odd piece of wood might survive. These earliest rune carvings have been found all over Northern Europe, even on occasion as far south as France, but most particularly around the Baltic Sea Coast. The messages would be brief, saying things like Vern made me. Not an actual Vern, there was no V. I’d carve this here if I could, carve it into light, but I’d have to use my own V.

The earliest runic inscriptions reveal no memory that the runes came from a prior alphabet, though they line up beautifully with several Latin letters, and correspond even more closely to Etruscan, the language of ancient northern and central Italy. F, R, C H, I, T, B, M are the same in the Runic and Etruscan alphabets, as well as U, S, and L if you rotate them, which they would. Runes could be written flipped the other way and form words written in any direction. Alphabets morph like that when they travel, some shapes stay, some get altered, some are left behind in the migration. Ask the rune carvers where the runes came from and they would not say Northern Italy, they’d say it was the Gods. And as such they are mysterious and secret. They are holy and sacred. They say things using the Gods’ mouth. They are the Gods’ mouth.

What are they saying? What did they first say? Shh. Whisper. Runes are secret. You think it’s a good idea to hear the secrets of the Gods and then go around blabbing to everybody just like that? It’s not. And that’s no secret.

Where do you go when you want to talk to the Gods? Receive their judgement? Find out what’s coming? The rune poem shows you in its structure. Don’t expect it to be straight like the grain of ash wood, this thing bends in the middle and curves back on itself, a helix entwined like roots and branches. The fourth rune in the sequence is Os, God. The fourth rune from the end is Æsc, Ash. You go to the ash tree. That’s where you go. The ash tree is where to get the Gods’ words, their voices. Why? It’s the world tree, it’s the axis mundi. It’s holding the whole thing up, Gods and all, so it better be firm in its foundations. You go there because at the base of the tree, which is really the middle, is the spot where there’s a universe above in the branches, and a universe below in the roots. Go there and you’ll be in the middle of it all. You are at the conduit between. You are the conduit between. You. The direct center. You’re what everything’s revolving around,

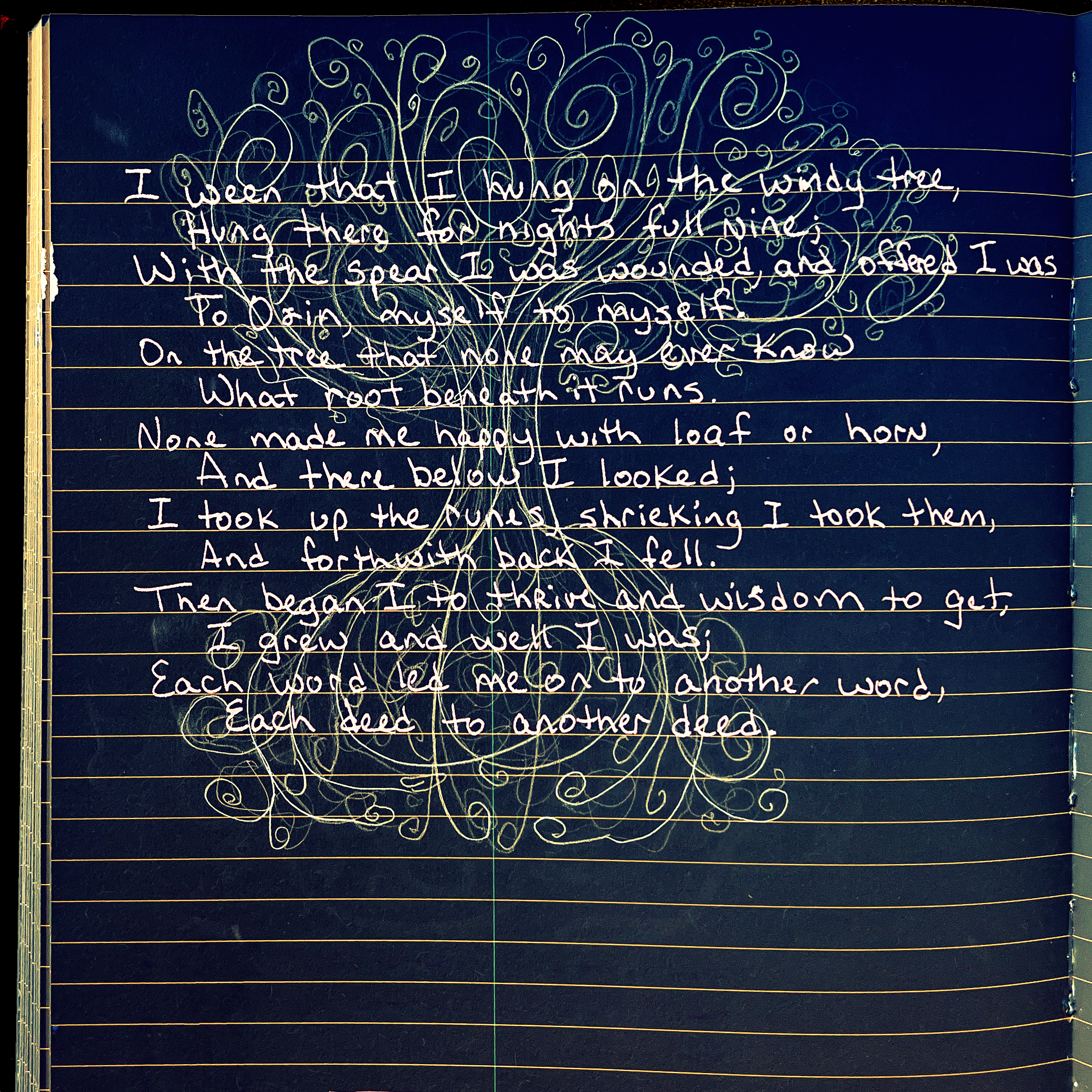

Which god pairs with the ash tree? Who sings the other half of the Ash Tree’s duet? To receive the runes, the Odin of the Hávamál self-crucified in an ash. He hung himself from a spear (presumably made of ash as the best spears would have been, a profane version of the sacred tree) as a sacrifice of himself in bodily form to himself the divine being. What could be a more valuable sacrifice to a God than a God? This is how you get something important like runes; they had to be valuable if this was the process. This was not just any ash tree either, it was Yggdrasill, the great world tree, the universe itself.

The oldest version of the Hávamál we have was written down in the thirteenth century, though it might date to the 9th or 10th centuries. It is likely the Rune Poem was first written down in the 6th century, from an oral tradition going back several centuries prior. In Britain at this time they worshipped Woden not Odin. Did Woden hang himself in an ash tree a thousand years before Odin’s sacrifice of self to self in the Hávamál? You should ask him. You know how.