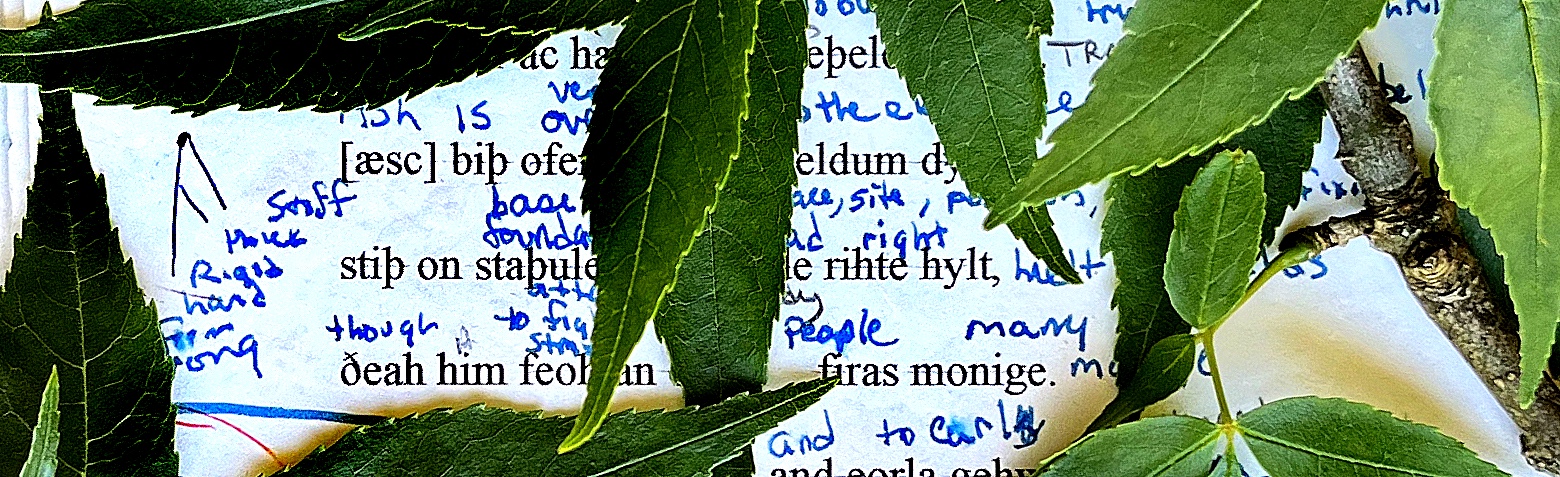

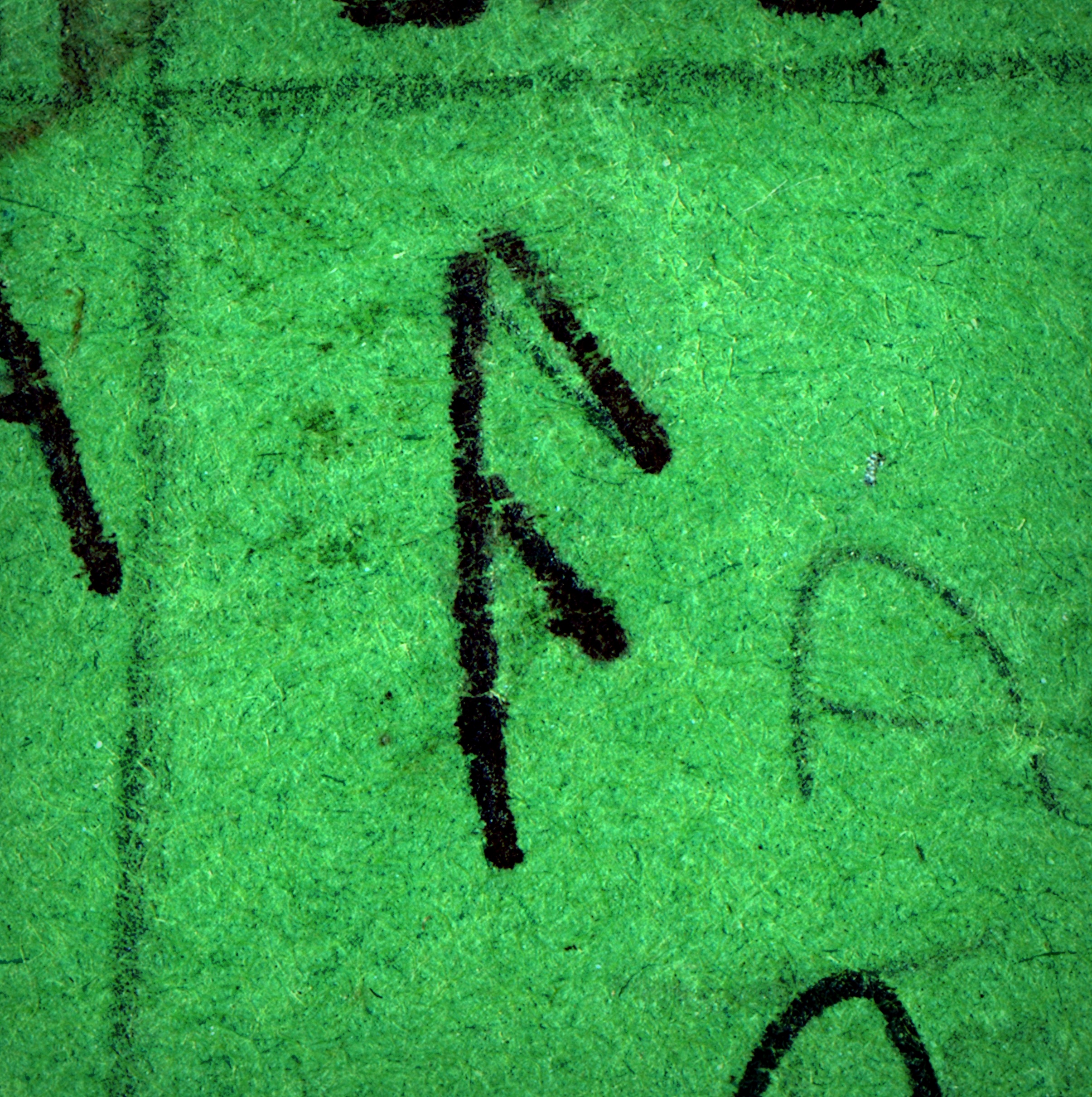

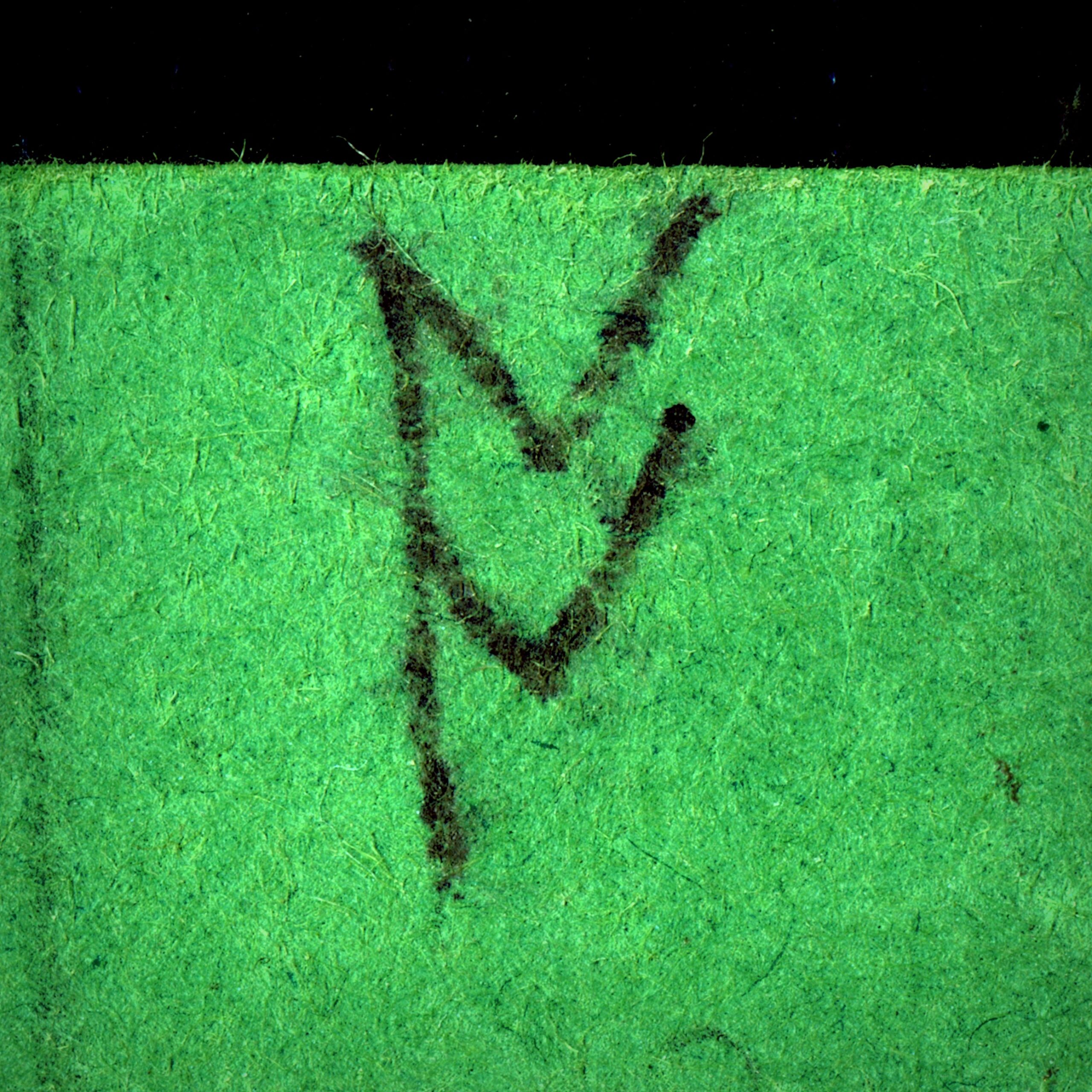

ᚫ biþ ofer heah. eldum dyre.

stiþ on staþule . stede rihte hylt.

ðeah him feohtan on firas monige ᛬᛫

It is very tall, dear to the elders

Firm in its foundations steadily, rightly, it holds

Though many people fight it.

The ash tree is oferheah. Over-high. Tall. And it grows from nothing: the smallest sapling can become something oferheah, massive, with root systems that are fairly shallow, but more extensive than most other trees growing in similar habitat. No wonder the stanza says it is stiþ on staþule, firm in its foundations. With far spreading roots like that it will stede rihte hylt, steadily and rightly hold firm in conditions that might cause another tree to topple. The wood from an ash tree is firm in another way too, it is a particularly hard wood and its grain grows straight, which makes it the ideal wood for a spear: it can take a powerful blow without splintering. Several blows. It also makes fantastic handles for axes and daggers. This is why the Rune Poem says him feohtan on firas monig: many people fight it, it made great weapons.

Don’t fight the … More

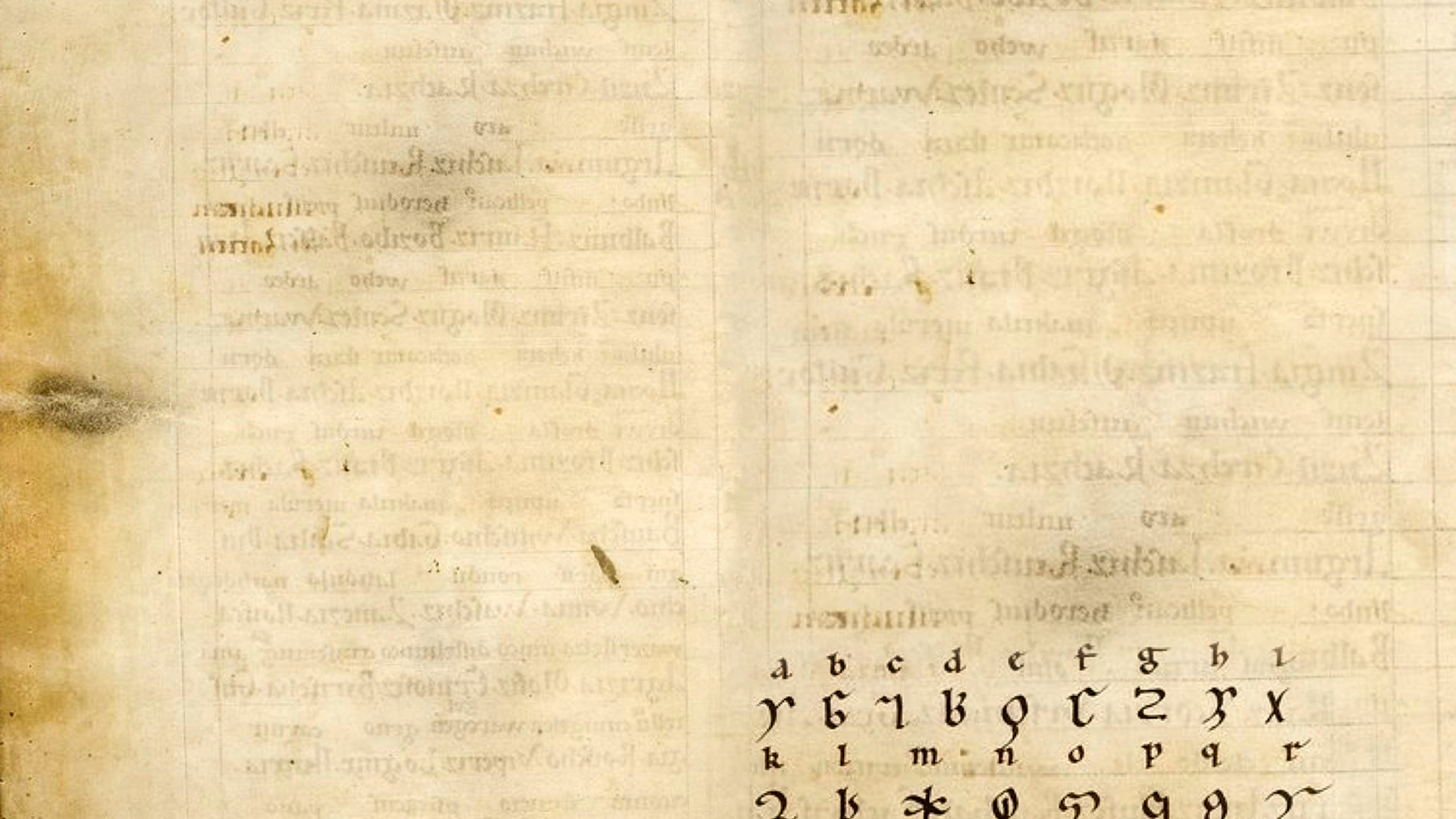

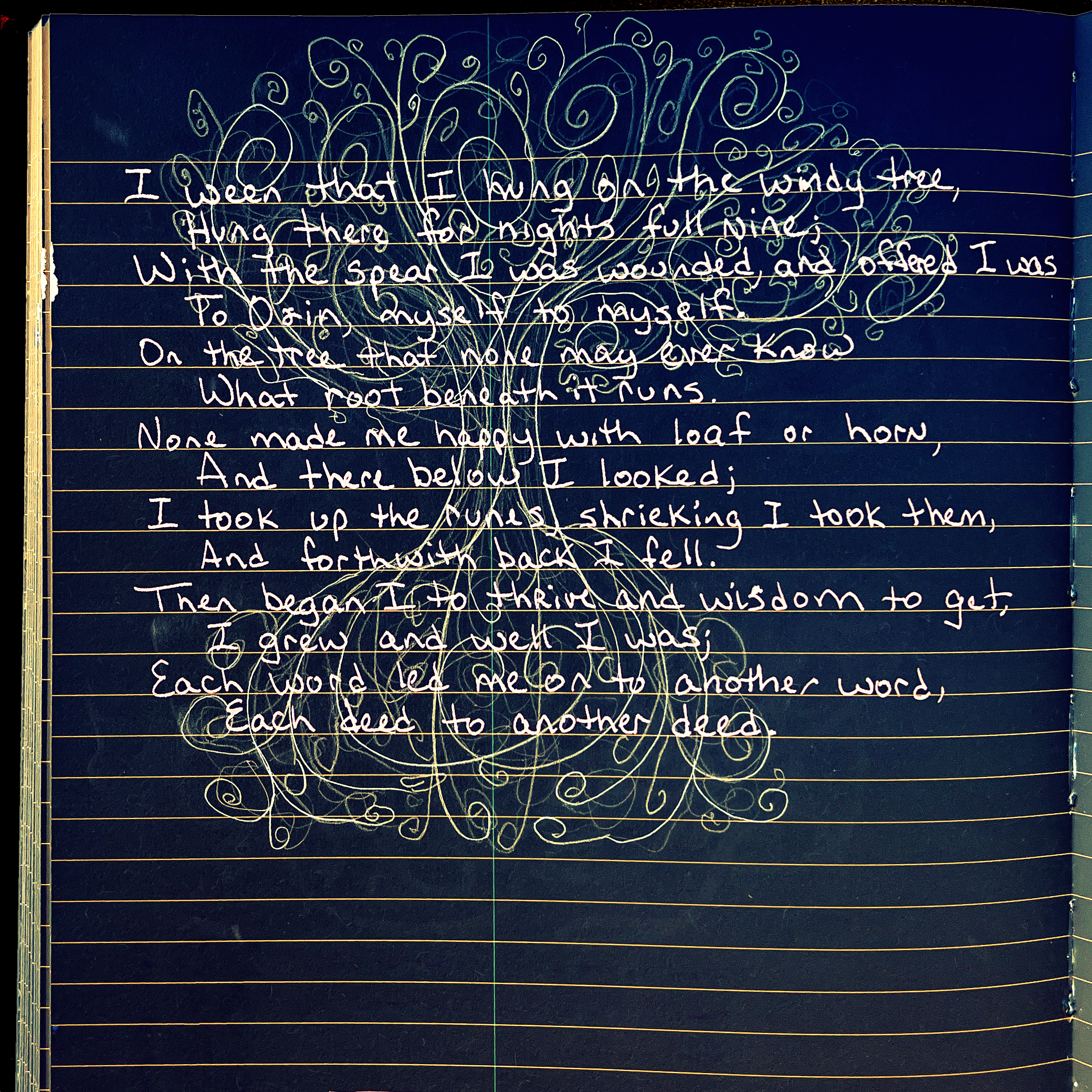

Archaeologists in their digging and dating trace the oldest runic alphabet back to the late second century. The oldest rune carvings are often of the alphabet itself, carved in order. They’ve found runes etched into durable things like rock, metal, bone, but sometimes the odd piece of wood might survive. These earliest rune carvings have been found all over Northern Europe, even on occasion as far south as France, but most particularly around the Baltic Sea Coast. The messages would be brief, saying things like Vern made me. Not an actual Vern, there was no V. I’d carve this here if I could, carve it into light, but I’d have to use my own V.

The earliest runic inscriptions reveal no memory that the runes came from a prior alphabet, though they line up beautifully with several Latin letters, and correspond even more closely to Etruscan, the language of ancient northern and central … More

You getting it from all sides? Lots of people want to take you on? Something’s coming for you, but this is the Æsc rune, and it is used to a good fight. It’s seen plenty of battles, and yours is no different. Æsc says stand tall and plant. You hold steady, firm in your foundations. Those roots you draw from go deep, farther than you know, all the way into your ancestry so connect with your elders, get right with them and hold.

You getting it from all sides? Lots of people want to take you on? Something’s coming for you, but this is the Æsc rune, and it is used to a good fight. It’s seen plenty of battles, and yours is no different. Æsc says stand tall and plant. You hold steady, firm in your foundations. Those roots you draw from go deep, farther than you know, all the way into your ancestry so connect with your elders, get right with them and hold.

The ᚩ rune (O, Os) and the ᚪ (A, Ac) both started the same way, as new shapes of the ᚫ rune (Æ, Æsc) which once made the sound of the letter A, stood in the fourth position of the alphabet, and meant God. The A sound changed very early in the lifetime of Old English, vowels are shifty, and this one changed into O and Æ, so new runes were made with new meanings to represent the new sounds, and appropriate places were found for them in the alphabetic line up. Æ, sounds like the A in ash tree, which is its meaning, this is one of a whole grove of trees in the Rune Poem. It kept the original rune shape ᚫ while the others are derived from it, and was moved opposite it’s original 4th position to the 26th place. They put it there so it can … More

The ᚩ rune (O, Os) and the ᚪ (A, Ac) both started the same way, as new shapes of the ᚫ rune (Æ, Æsc) which once made the sound of the letter A, stood in the fourth position of the alphabet, and meant God. The A sound changed very early in the lifetime of Old English, vowels are shifty, and this one changed into O and Æ, so new runes were made with new meanings to represent the new sounds, and appropriate places were found for them in the alphabetic line up. Æ, sounds like the A in ash tree, which is its meaning, this is one of a whole grove of trees in the Rune Poem. It kept the original rune shape ᚫ while the others are derived from it, and was moved opposite it’s original 4th position to the 26th place. They put it there so it can … More

Vowels are slippery things. They shift around and we have to learn which sound differences to ignore as another person’s accent and which ones change meaning. In the earliest times of Old English history the sound of the letter A changed so much it became three letters, A (ᚪ), O (ᚩ), and Æ (ᚫ). The ᚫ rune was the original rune shape for the A sound and stands in the 4th position in the Norwegian and Icelandic runic alphabets where it makes the sound for the letter A and means God. In the Old English runic alphabet, ᚩ (Os) holds the 4th position where it still means God, but here it makes the sound O. Smote. Lot. That God that smote you is a lot. The O sound was once made by the ᛟ rune, Eþel, but by the time they wrote down the Rune Poem, Eþel was already slipping … More

Vowels are slippery things. They shift around and we have to learn which sound differences to ignore as another person’s accent and which ones change meaning. In the earliest times of Old English history the sound of the letter A changed so much it became three letters, A (ᚪ), O (ᚩ), and Æ (ᚫ). The ᚫ rune was the original rune shape for the A sound and stands in the 4th position in the Norwegian and Icelandic runic alphabets where it makes the sound for the letter A and means God. In the Old English runic alphabet, ᚩ (Os) holds the 4th position where it still means God, but here it makes the sound O. Smote. Lot. That God that smote you is a lot. The O sound was once made by the ᛟ rune, Eþel, but by the time they wrote down the Rune Poem, Eþel was already slipping … More