In the Old English Rune Poem, Ing is specifically masculine pronoun male. He’s a boy. But where Ing came from amongst the East Danes of what is now eastern Denmark and Southern Sweden, Ing appears to be a deity who was sometimes male, sometimes female, sometimes both at once. This is not uncommon, there are crowds of intersexed deities in world belief systems. I was going to list them. I don’t have enough space. But anywhere we look, there they are, including if we look toward Ing’s people. We have to look close, we have very little to go on.

In the Old English Rune Poem, Ing is specifically masculine pronoun male. He’s a boy. But where Ing came from amongst the East Danes of what is now eastern Denmark and Southern Sweden, Ing appears to be a deity who was sometimes male, sometimes female, sometimes both at once. This is not uncommon, there are crowds of intersexed deities in world belief systems. I was going to list them. I don’t have enough space. But anywhere we look, there they are, including if we look toward Ing’s people. We have to look close, we have very little to go on.

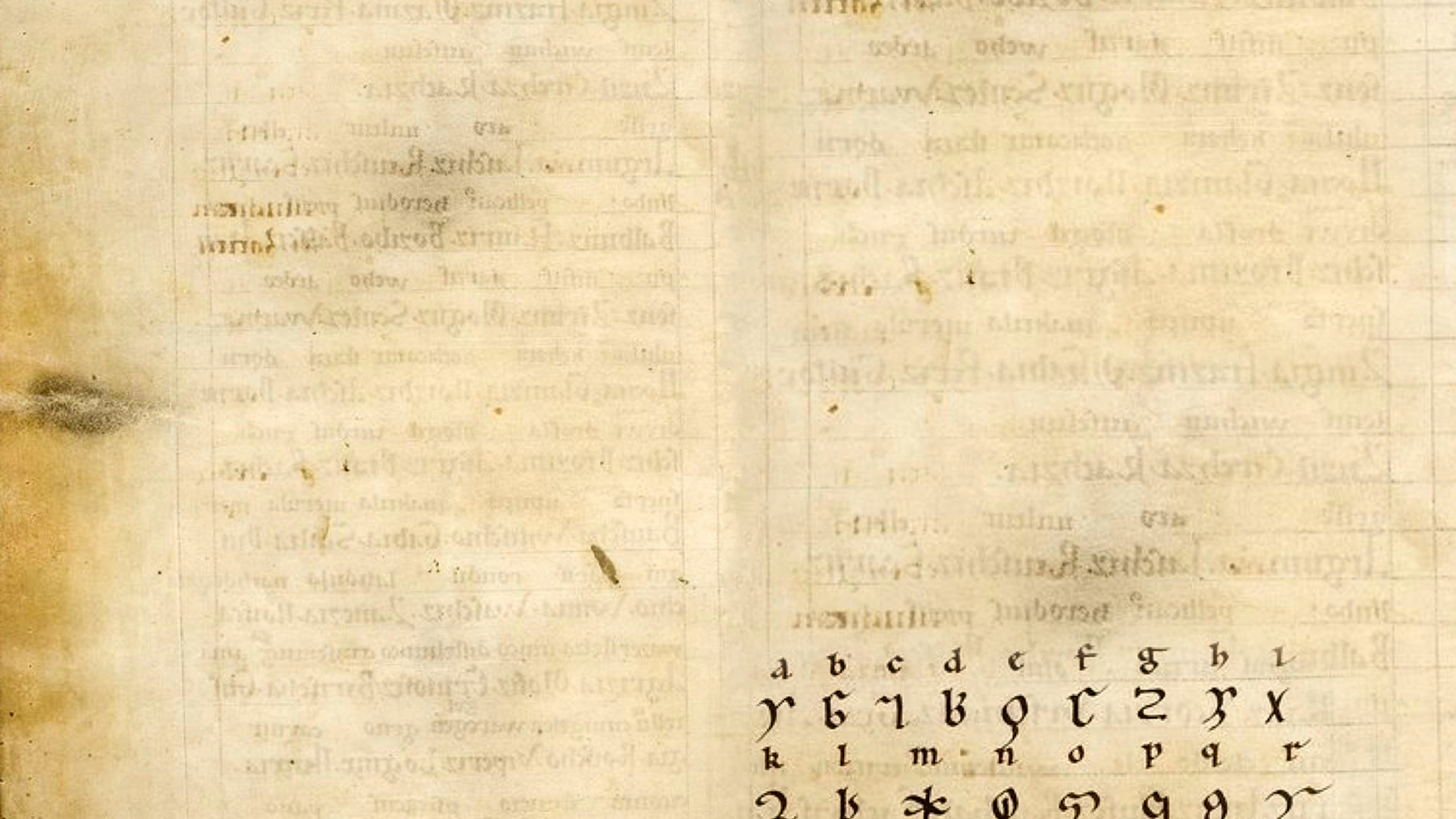

We also have to look at Ing’s people at the wrong times which is always tricky. Ing is called Ing in the Rune Poem, which was most likely written down in the 600’s but is probably several hundred years older than that. The runes themselves are certainly older. When Ing is called Ing in the Rune Poem he is described as somebody from the past. He’s old to the rune carvers. He’s gone and doesn’t pop up again until 600 more years into the future when Snorri Sturluson writes about Ing’s descendants.

One of Ing’s more important descendants and Snorri’s Sturluson’s main audience was King Haakon IV, a teenager with too much power and not enough sense. He liked Snorri. Snorri was a rock star. He sang the best stories and it’s a good thing too, most of what we know about Norse mythology comes from Snorri’s efforts to impress an impressionable young king. It absolutely worked, it’s good to dazzle the money. This was a culture that made a big thing about being generous, and Snorri got his. It was nice.

King Haakon had a tenuous hold on his throne, as you can imagine somebody going through puberty might. Likewise Snorri’s homeland of Iceland was barely hanging onto its sovereignty due to plenty of infighting. Young King Haakon knew quite a lot about Iceland, thanks to Snorri, and wanted Iceland to be a part of Norway, so he sent Snorri home with a massive amount of political power and an agenda to deliver Iceland to him via political means. Snorri the poet made an effort and destabilized the whole place by not being an actual politician. Iceland ultimately lost its sovereignty to Norway and Snorri lost his close connection with the king, who had him assassinated, leaving behind several mothers of his children and the Prose Eddas. Kings can be fickle. Snorri Sturluson left for himself a mixed legacy of being a hero to some, a traitor to others, and a coward in the Sturlunga Saga, written down by his own family. Families can be treacherous.

What does Snorri Sturluson say about Ing? He says the Ynglingar are descendants of Yngvi-Freyr, the deity who presides over prosperity and is the husband of Ingun. That’s Ingun with an Ing. Yng is Ing. Is Ing also Freyr, the Norse god people still remember? Freyr is much more famous than Ing. You know who this is, Freyr and Freya both. They are sometimes twin siblings, sometimes consorts, they have a cart and they preside over fertility and prosperity. Exactly like Ing.

It seems from the evidence that Ing was male but over time became two genders. However, look much further back from the time of the Rune Poem and the truth is Ing was gender fluid all along. In the thirteenth century Snorri says this Yngvi-Freyr, consort, brother, and other half to female Ingun, is the child of Njörðr, or Niord. We’ve heard a name like this before and in the exact same place. A full millennium plus a couple hundred years prior to this Njörðr, in the first century of the common era, Roman historian-anthropologist-reporter Tacitus describes in his Germania a coastal people who worship a cart riding deity of fertility and prosperity. This goddess is called Nerthus, or the proto-germanic Nerþus, pronounced just like Njörðr but with a slightly different sound at the end.

This is a thousand plus a few hundred years long game of telephone Ing is right in the middle of, and things have changed. During the first century Nerþus is female, at least when Tacitus was visiting, though he describes her priest as a man in drag; gender duality seems to have remained as a part of this deity’s picture from the beginning. Tacitus says in his report about Nerþus’ people that they hold sacred an island in the ocean. He means Zealand, the home of the East Danes, where the Rune Poem says Ing was first seen and spoken of. On this island Nerþus’ people watch over a sacred grove where they keep a cart covered with a veil that only Nerþus’ priest may touch. During one season of the year they yoke cattle to the cart and the goddess is driven through the fields to visit every community. Wherever she goes peace goes with her. No wars are fought, weapons are shut away lest they offend her, and this is the only time the people know peace and love it. At the end of her tour Nerþus goes home to her grove “satiated with mortal intercourse” and in need of a bath. Her whole cart with its curtain (was the curtain ever pulled back during the mortal intercourse?) and Nerþus herself, though Tacitus seems doubtful on this point for some reason, are bathed in a secret lake by attendants who are drowned immediately after.

The Rune Poem says nothing about Ing’s worship involving human sacrifice, maybe it happened maybe it didn’t, we don’t know. We do know that in all of these versions of Ing, the deities have carts and presided over fertility and prosperity in the market, and appeared seasonally in the fields. We can imagine from this that perhaps the masculine Ing of the Rune Poem had a female aspect as well, that he was also she: a monad and a double act. Some things we’ll never know for certain, though it does seem quite likely that the rune carvers’ god Ing, was a goddess too.