You can’t have a society without a collective understanding of time. You can’t. Show me one. Time is the basis of everything: our idea of shared reality, what we think happens after we die, every question of faith, every approach to proof, everything. There are great similarities from culture to culture about the big mathematical details. For example, some have noticed that the sun moves the distance of its own radius every minute, it’s why we have a minute. It’s in the stuff we can’t prove and quantify where we can really see the personality of a people.

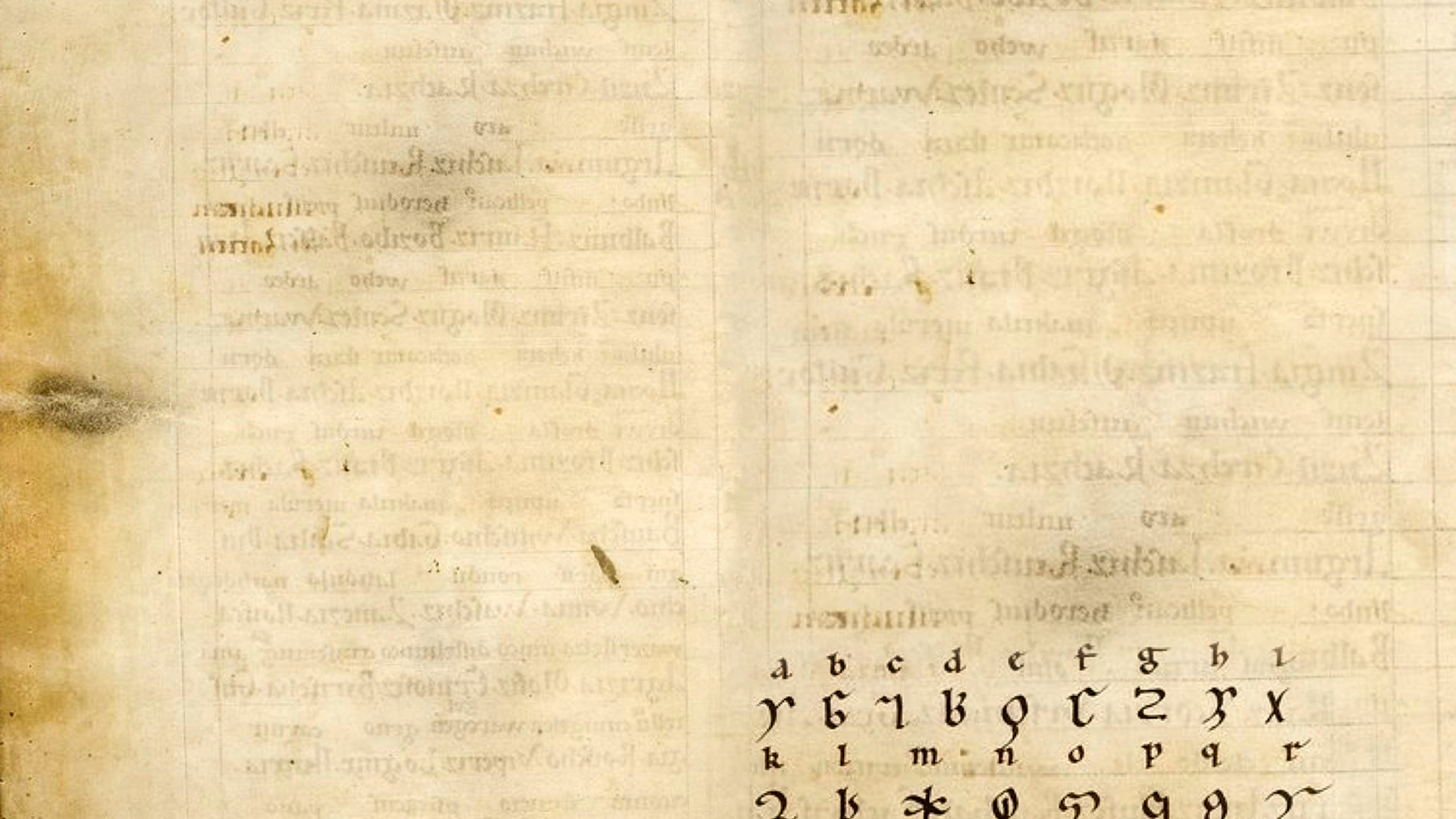

This pairing of runes, Beorc and Ger, Birch and Year, reveals what happens to a culture’s sense of time when their abundance waxes and wanes rather drastically with their living conditions. These were coastal people whose challenging waters range from confronting to inhospitable. Their cold inland weather has its own difficulties and everything depends upon the growing season, which is short. By the time you are deep into winter, counting the weeks into the upper teens, you’ve had to slaughter valuable livestock because it’s been eating too much and you are running out of your own food. You’ve had nothing green and fresh since harvest, you’ve been grinding the inner bark of birch trees to add to whatever other grain you have left, make it stretch, and it’s still icy out there. The ground is still frozen. The sea is still frigid. When all this puts everybody in need, the bearnum and ðearfum, the rich and the poor doesn’t matter who, the start of spring becomes intensely important. The beginning of the new ger, the return to abundance, this is what everybody wants. This is what everybody is hoping for, watching all the signs. How do you know it has arrived? It’s when the beorc starts leafing out. The birch is the first tree to show its new spring growth and let us all know everything’s coming back. It’s time again, thank the gods. All the dead fields, leafless trees without fruit, berries, nuts, it’s all returning. Animals, birds, fish will be more plentiful and easier to hunt, chickens will start laying eggs again, and you will get to eat and get to work: farm, fish, trap, hunt, gather, put stuff by for the future because winter time is lean.

How is the summer food production going to go? How will you prevent being hungry next winter? You will want this information beforehand. The Birch stanza informs us we can use its branches for divination, to find what the movement of time will bring us next. The Year stanza is about the end of anticipation, the arrival of the hoped for future, the movement of time into the new. These were a people who enjoyed knowing what comes next, a culture steeped in divination as a way of life, and they looked to the plants for their information. If it gives fruit or is the portent of spring you can also eat, like the birch tree, then you can carve potent letters into its pieces and use it to know the future.

Yet Old English has no future tense beyond the sense of the endless duration of lasting things. For an Old English speaker to communicate about their portents, the structure of their language puts the future into the present moment. If it is going to be, then it is now. It is, in a way that always was and ever shall be. This is how they thought about time. We do it a bit differently. Our future is out there, down a long road that stretches far both ways, and only both ways, with some haziness in the distances distorting the view. But when you think in Old English, the version of the future you hold hugs you back right up close. The future abides in the arms of the present, which does make sense. What is the future but present hope or fear? When we see something is to come, or even think it, or fear it or hope for it, we feel it now. We live with it now. And we had better plan for it now because summer time is short.

Both Birch and Year use the word bleda, the genitive plural form of bled or blaed: of fruits, of blossoms or flowers, of leaves or shoots or crops. It takes on the sense of offspring in the Birch stanza. Blaed also means prosperity and abundance as it does in the Joy stanza, and it means blowing, breath, and even inspiration as it does in the Home stanza. In the Grave stanza bleda are overripe fruits that fall to the ground dying, and in the Year stanza where all these meanings apply, bleda are the new shoots and blossoms coming to the earth, growing and spreading, seeds breathed by wind, floating to new places to begin the cycle of life to death again.