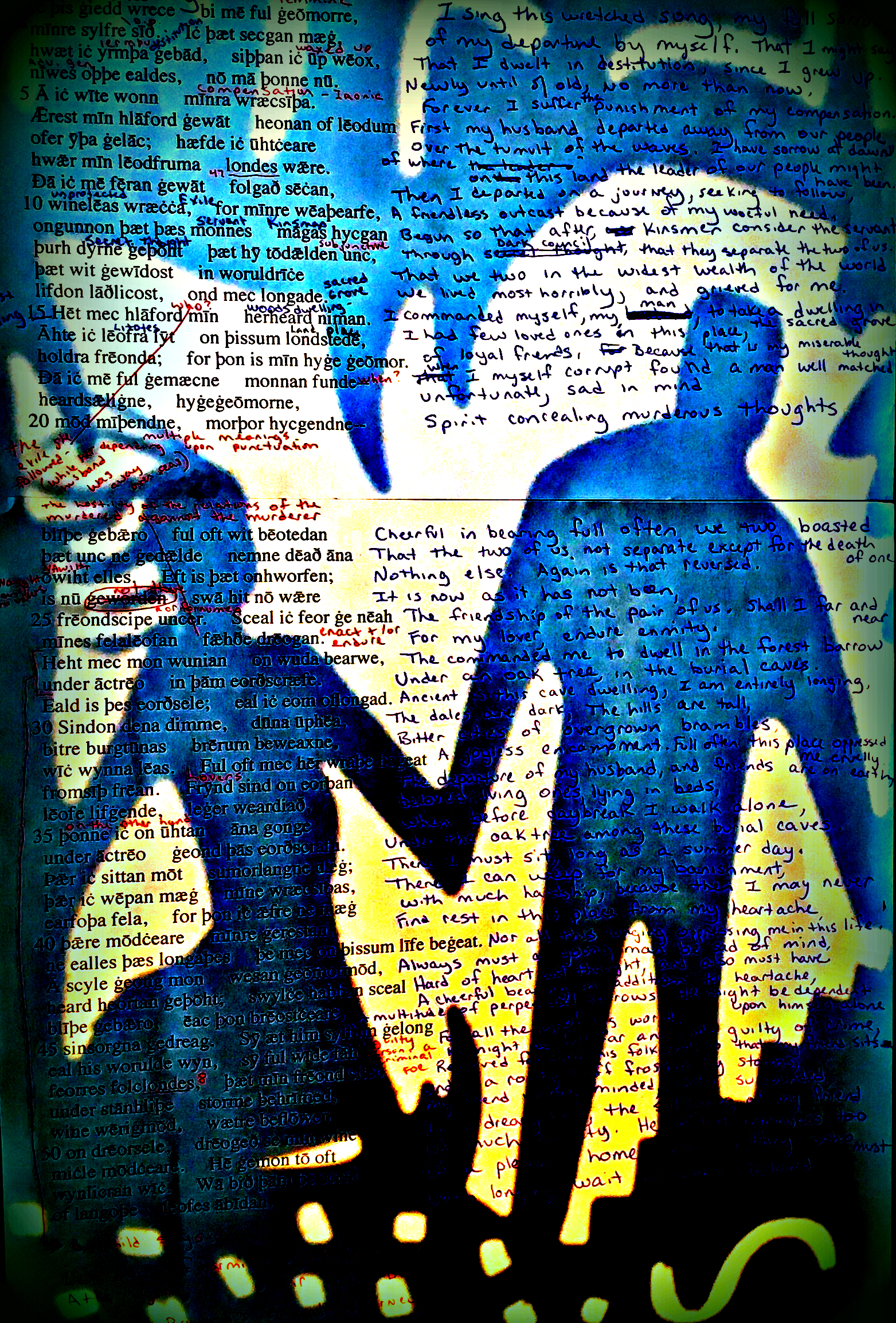

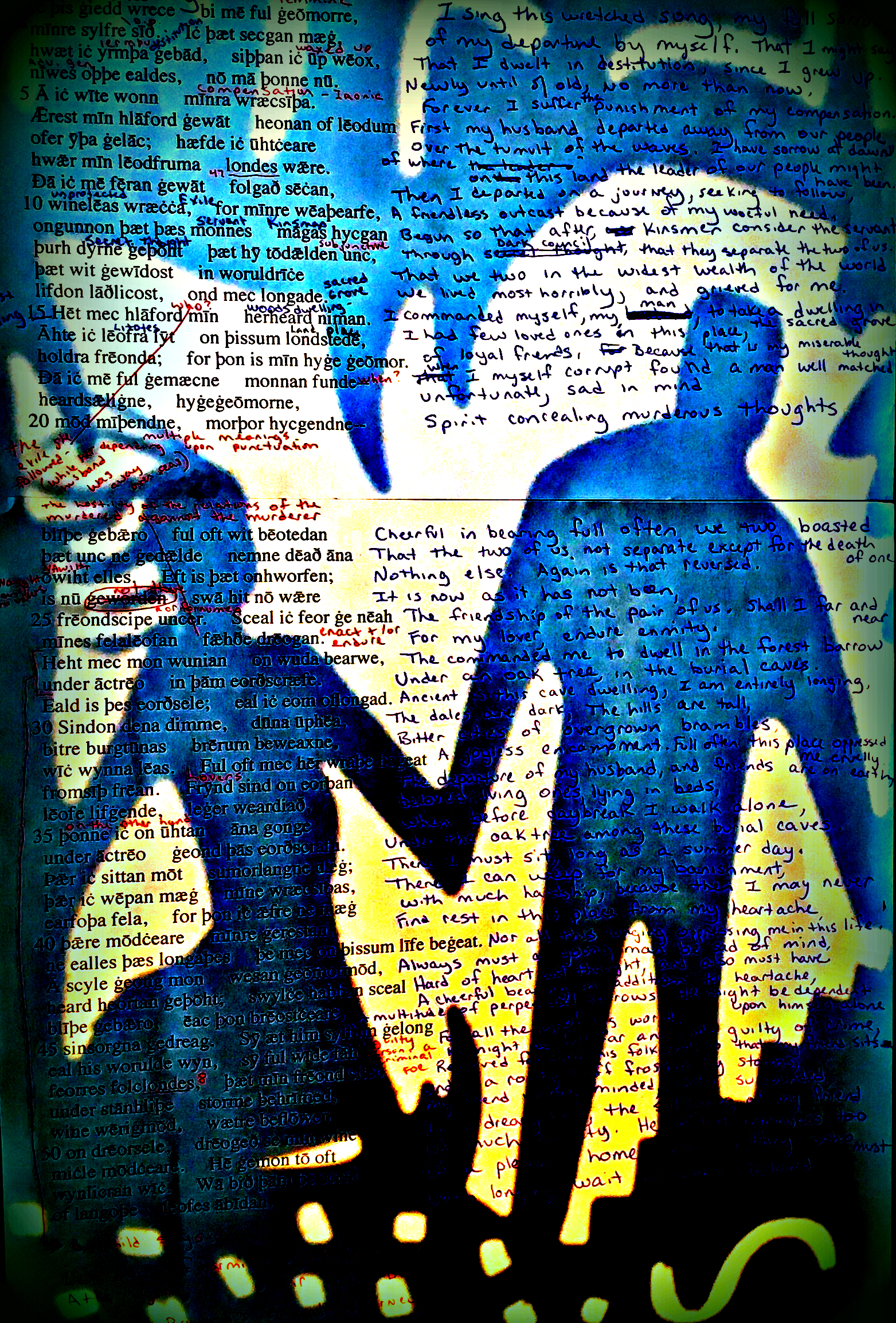

I sing this wretched song, my full sorrow

I sing this wretched song, my full sorrow

Of my departure by myself, that I might speak

That I dwelt in destitution, since I grew up,

Newly until of old, no more than now,

Forever I suffered my compensation, a journey of exile.

First my husband departed away from our people,

Over the tumult of the waves; I have sorrow at dawn

Of where on this land the leader of our people might have been.

Then I departed on a journey, seeking to follow

A friendless exile, because of my woeful need.

I began so that after, my kinsmen consider the servant

Through secret council, that they separate the two of us,

That we two, in the widest wealth of the world

Lived we most horribly, and grieved for me.

I commanded myself, my man, to take a dwelling in the sacred grove,

I had few loved ones in this place

Of loyal friends, because … More

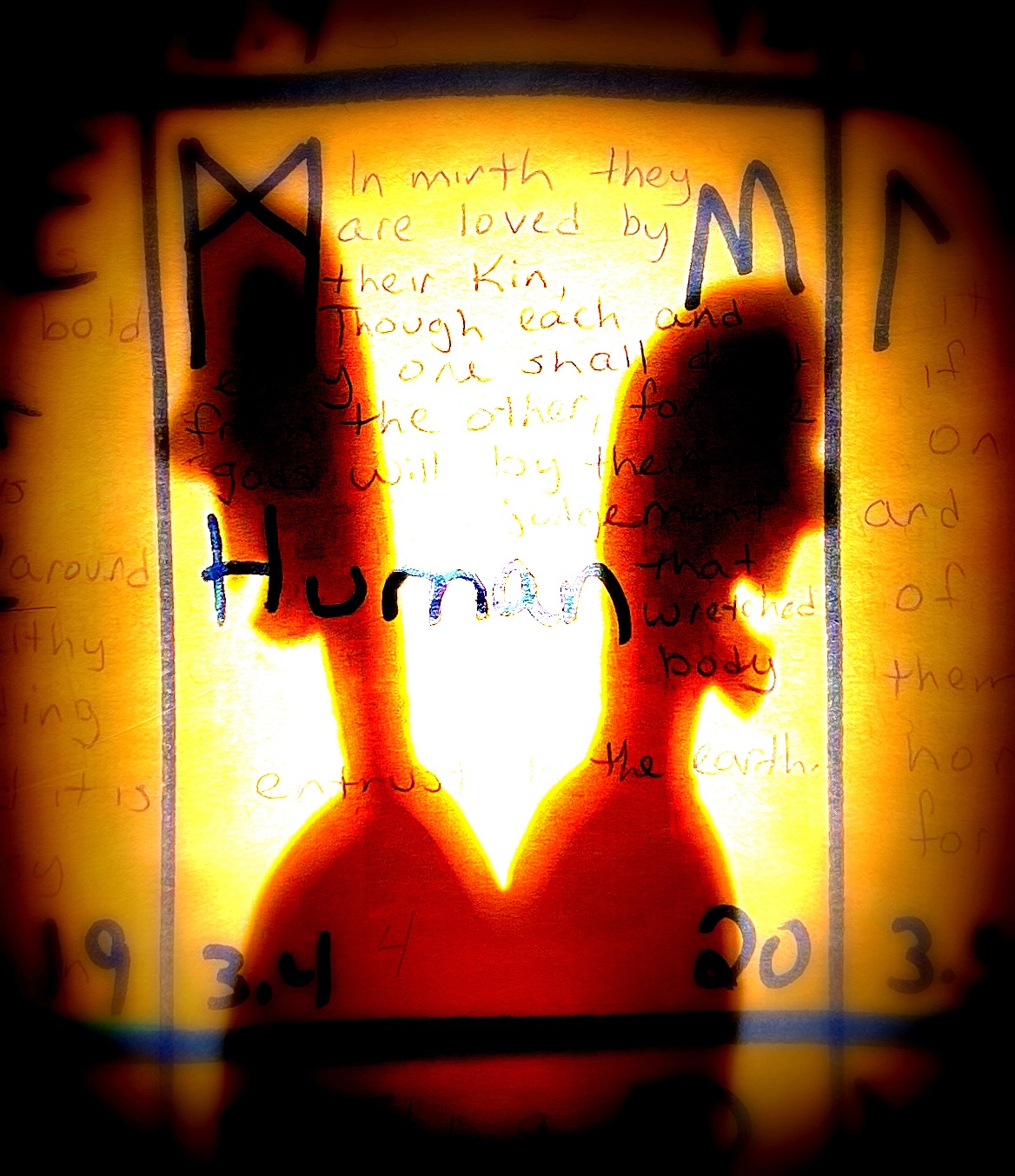

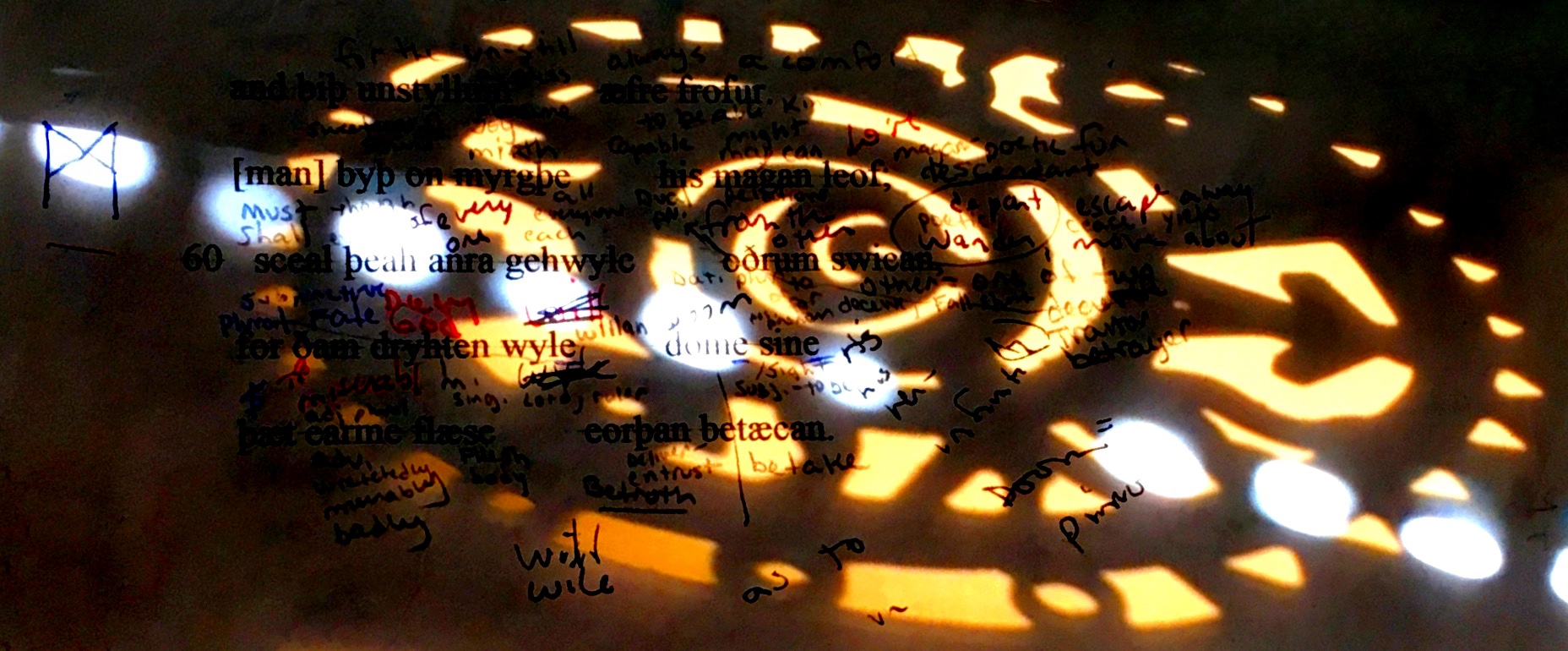

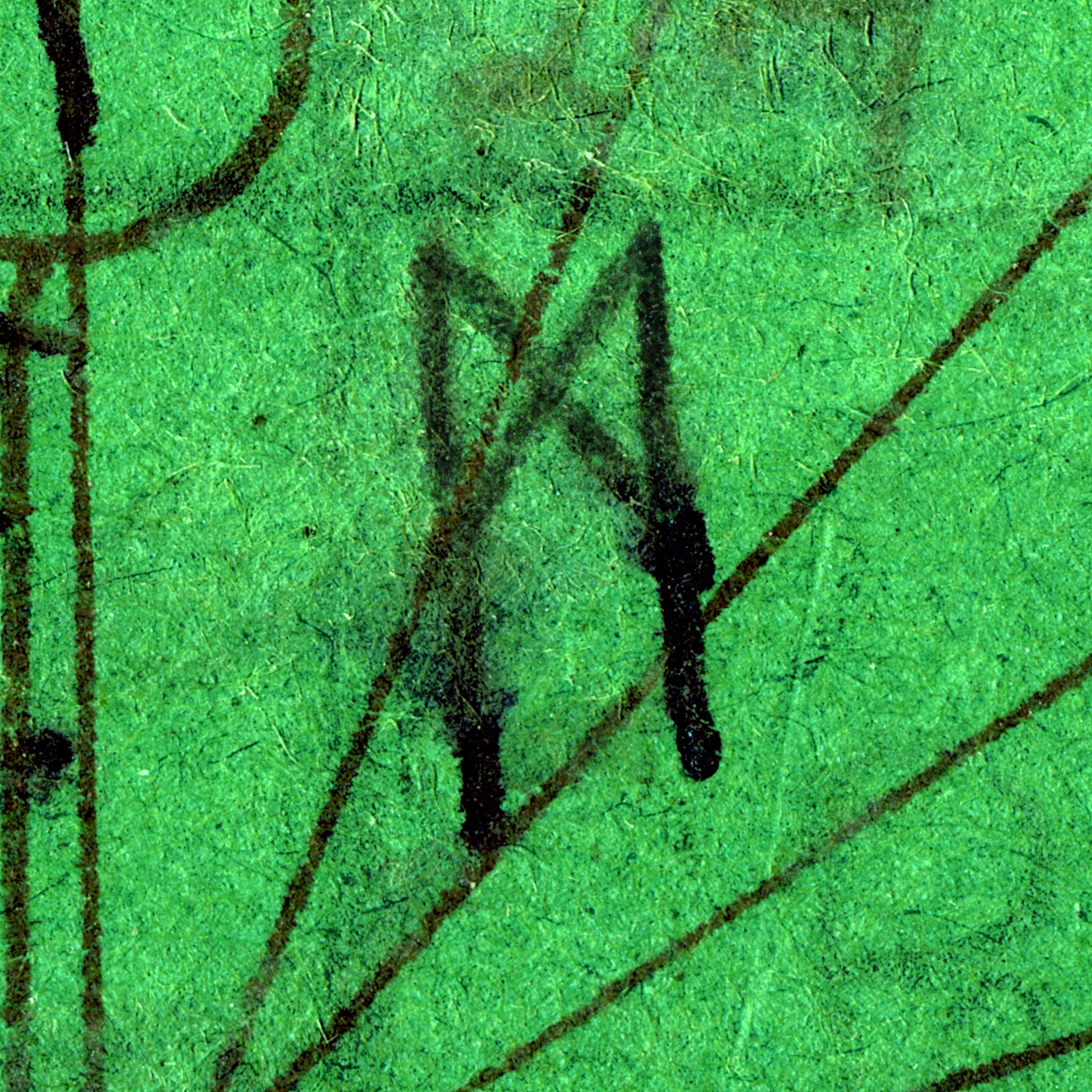

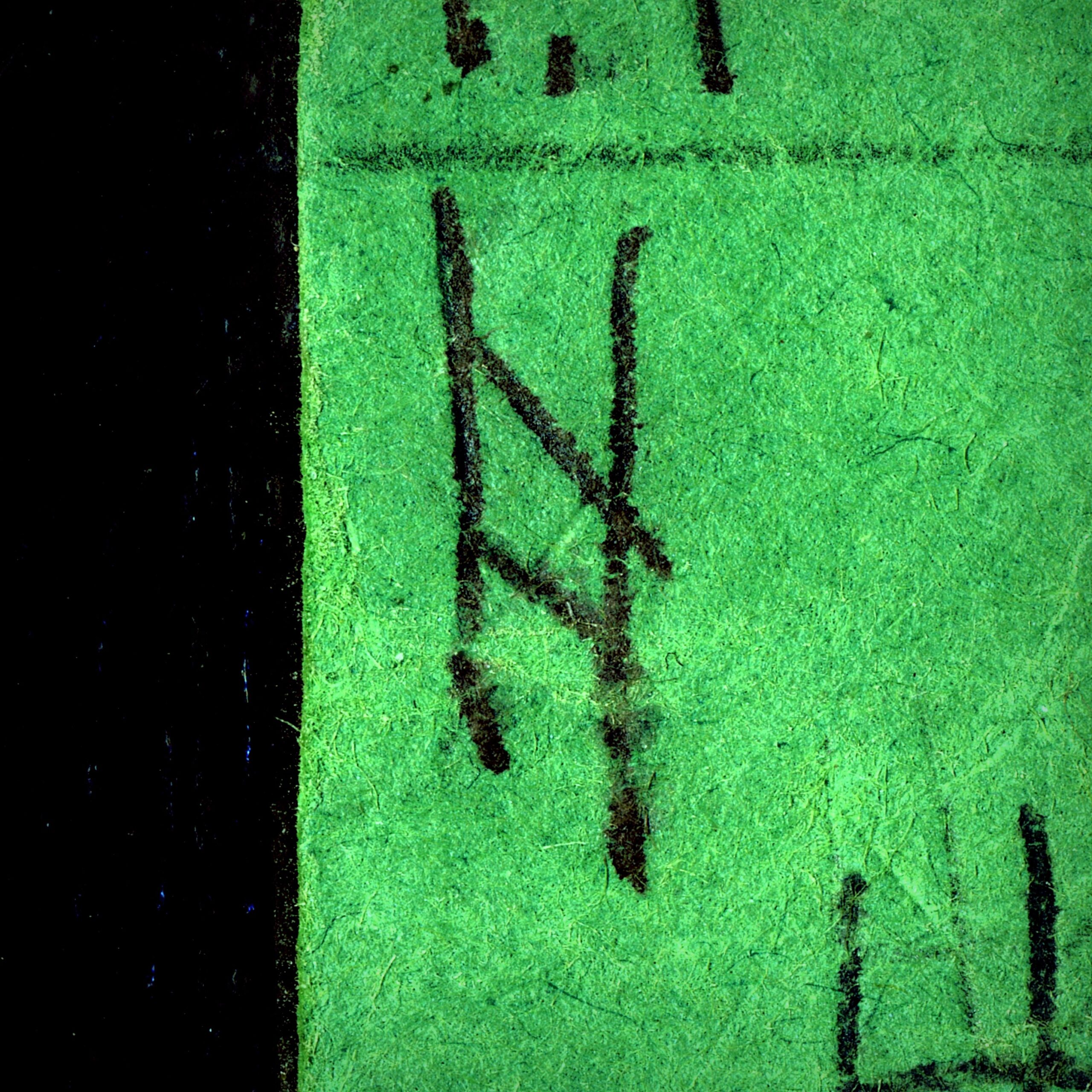

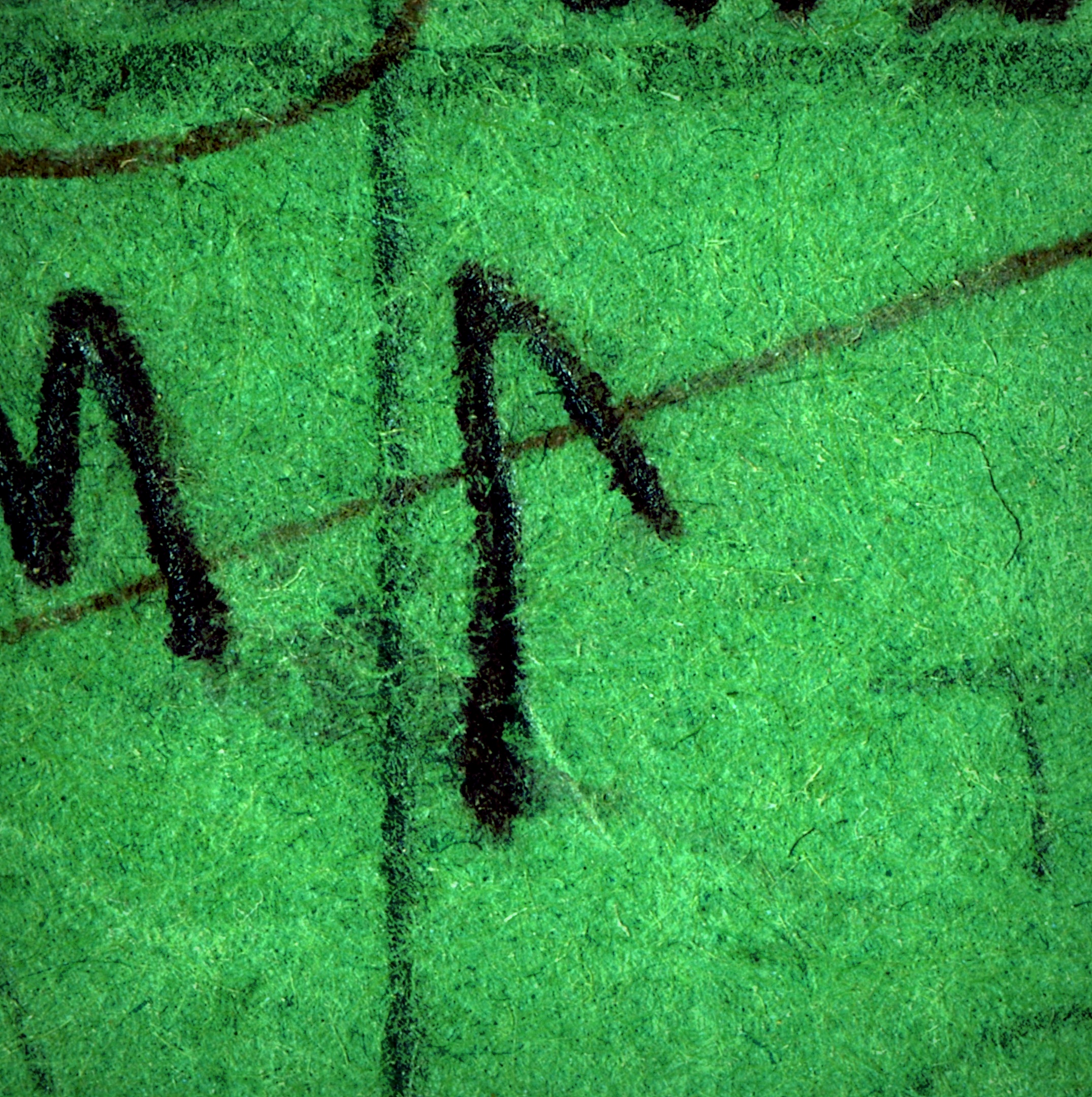

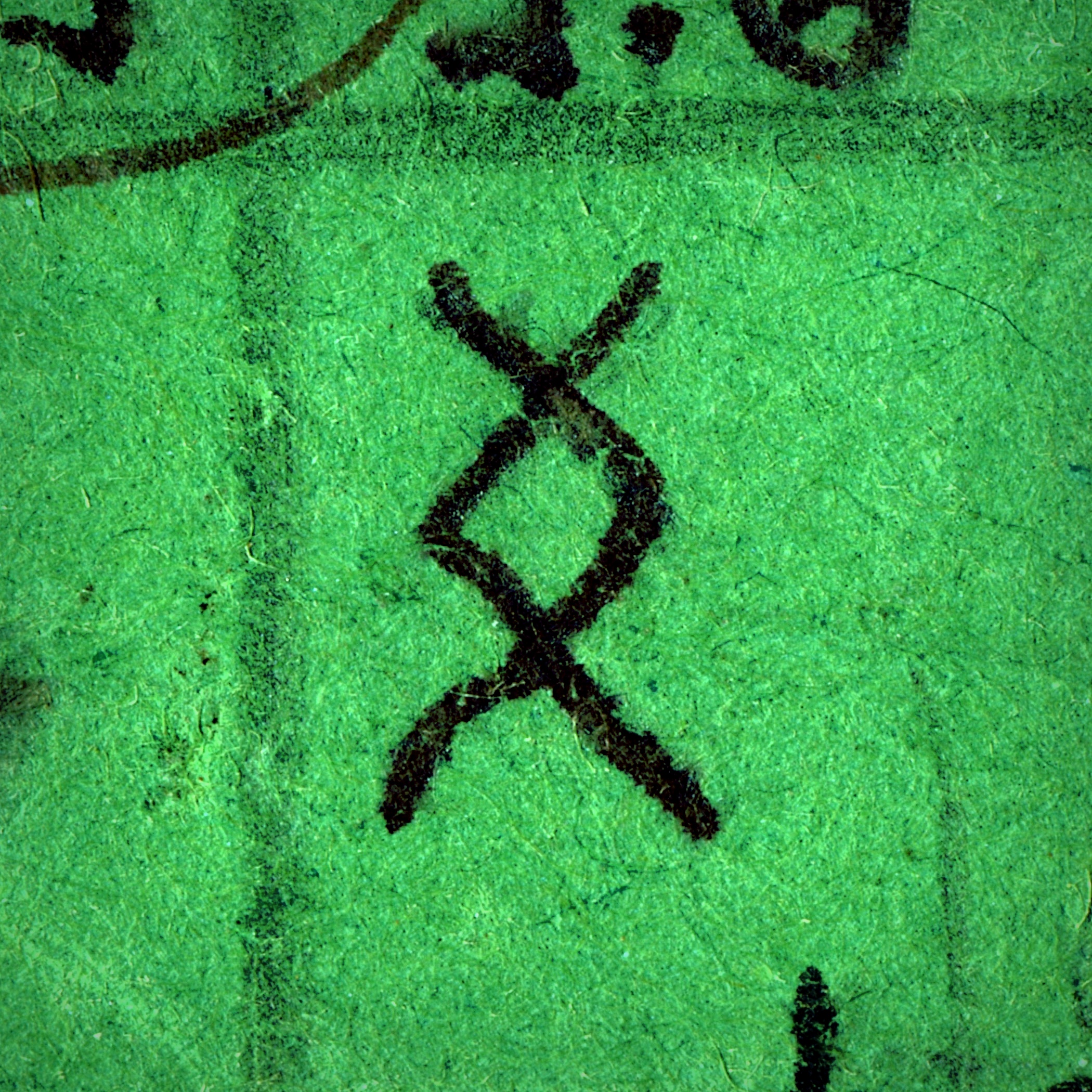

ᛗ byþ on myrgþe his magan leof.

ᛗ byþ on myrgþe his magan leof.

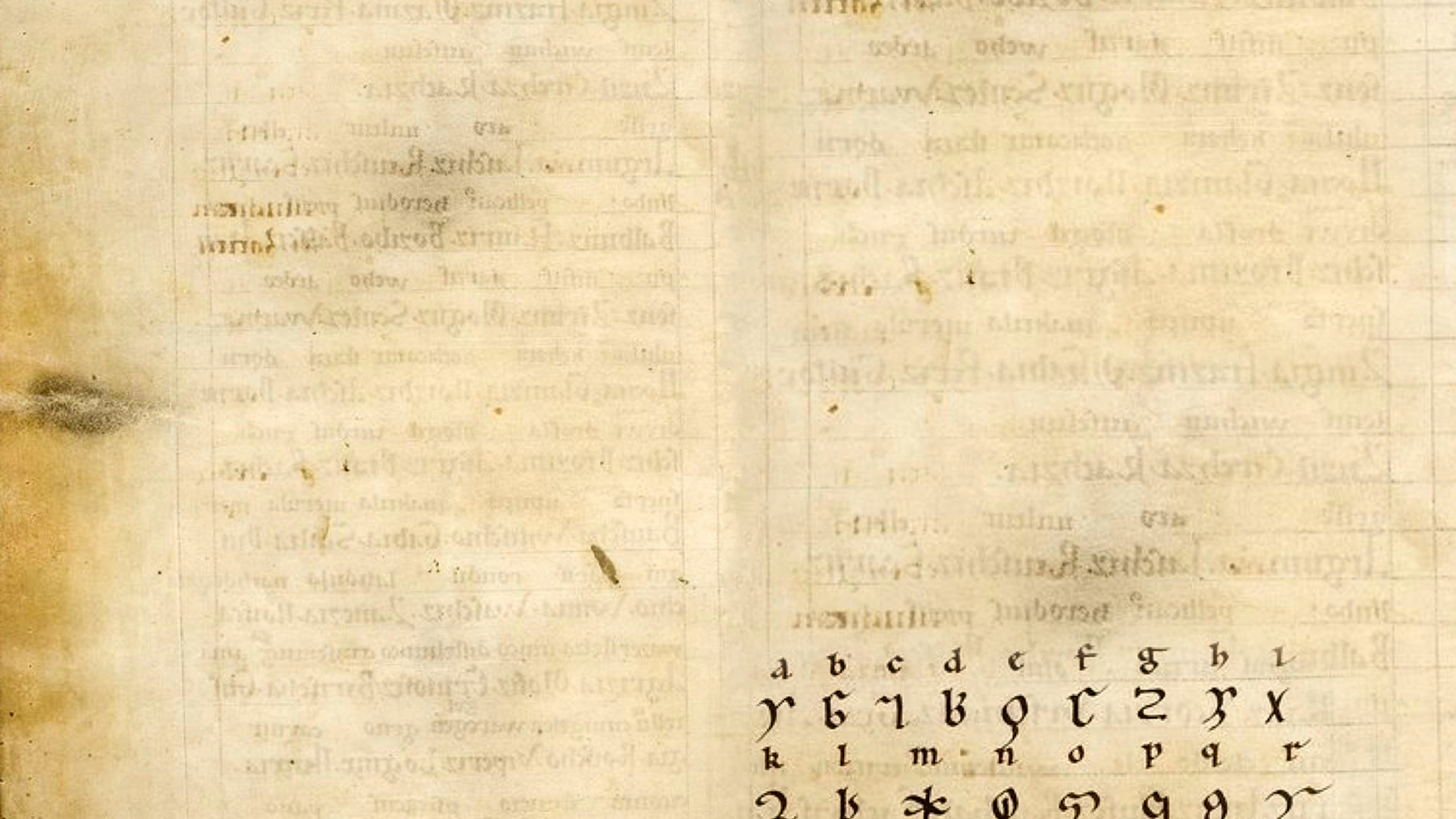

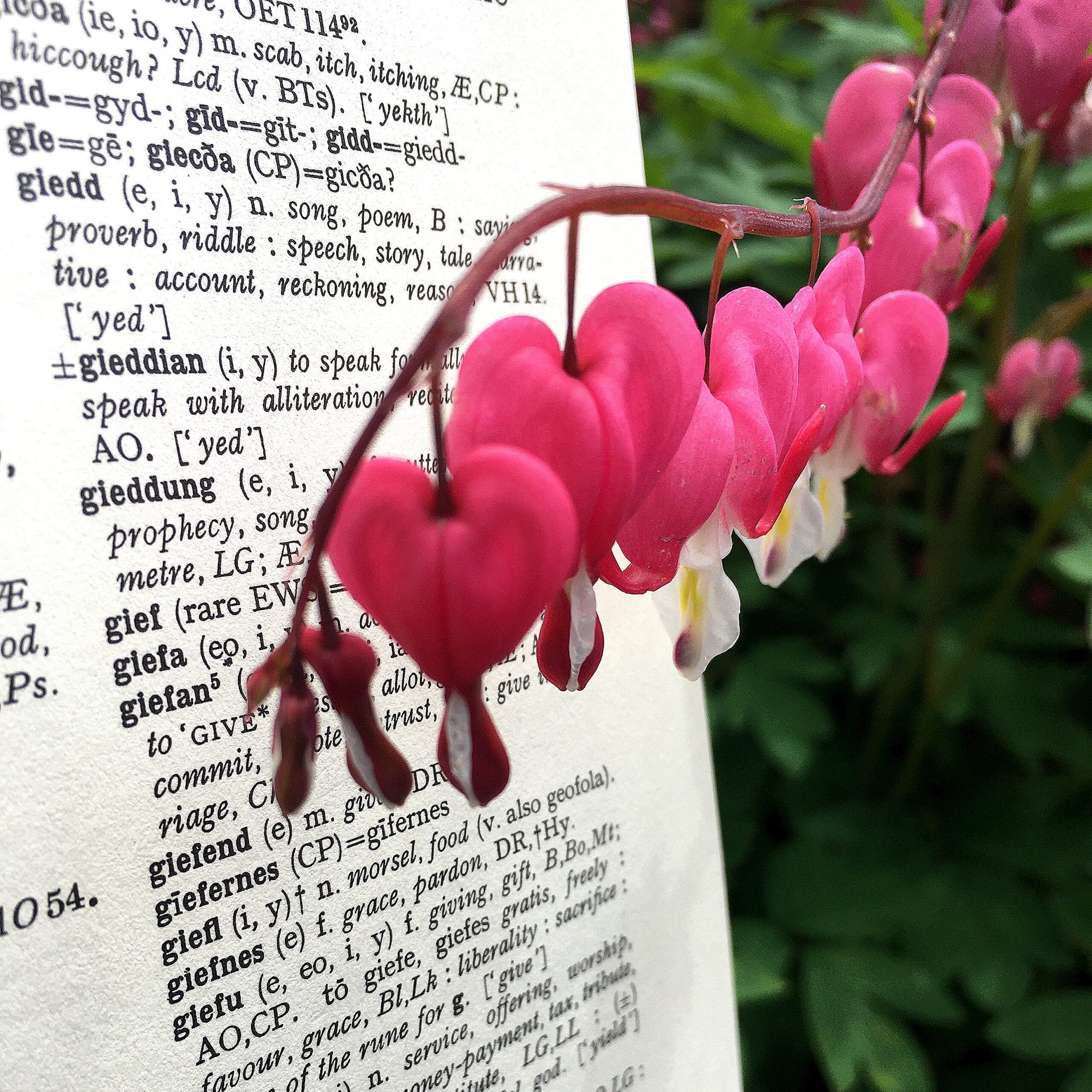

In Old English, a mann is a human being of any gender, translated into modern English as anyone, they, people, a citizen, a human. Mann is not a male person here, so when you see Mann as the name of this rune, it does not mean man as in male. Most correctly it can be either Person or Human but I need to pick one: Human. Person says more about ourselves as bodies. We carry things on our person, we are a person in a room. We are also a human in a room, but we do have a collective human nature, a human understanding, and human sensibilities. Human is a word that suggests the connection we have from our shared experience of being people in the world. It’s a choice that feels right to me as an answer to

In Old English, a mann is a human being of any gender, translated into modern English as anyone, they, people, a citizen, a human. Mann is not a male person here, so when you see Mann as the name of this rune, it does not mean man as in male. Most correctly it can be either Person or Human but I need to pick one: Human. Person says more about ourselves as bodies. We carry things on our person, we are a person in a room. We are also a human in a room, but we do have a collective human nature, a human understanding, and human sensibilities. Human is a word that suggests the connection we have from our shared experience of being people in the world. It’s a choice that feels right to me as an answer to

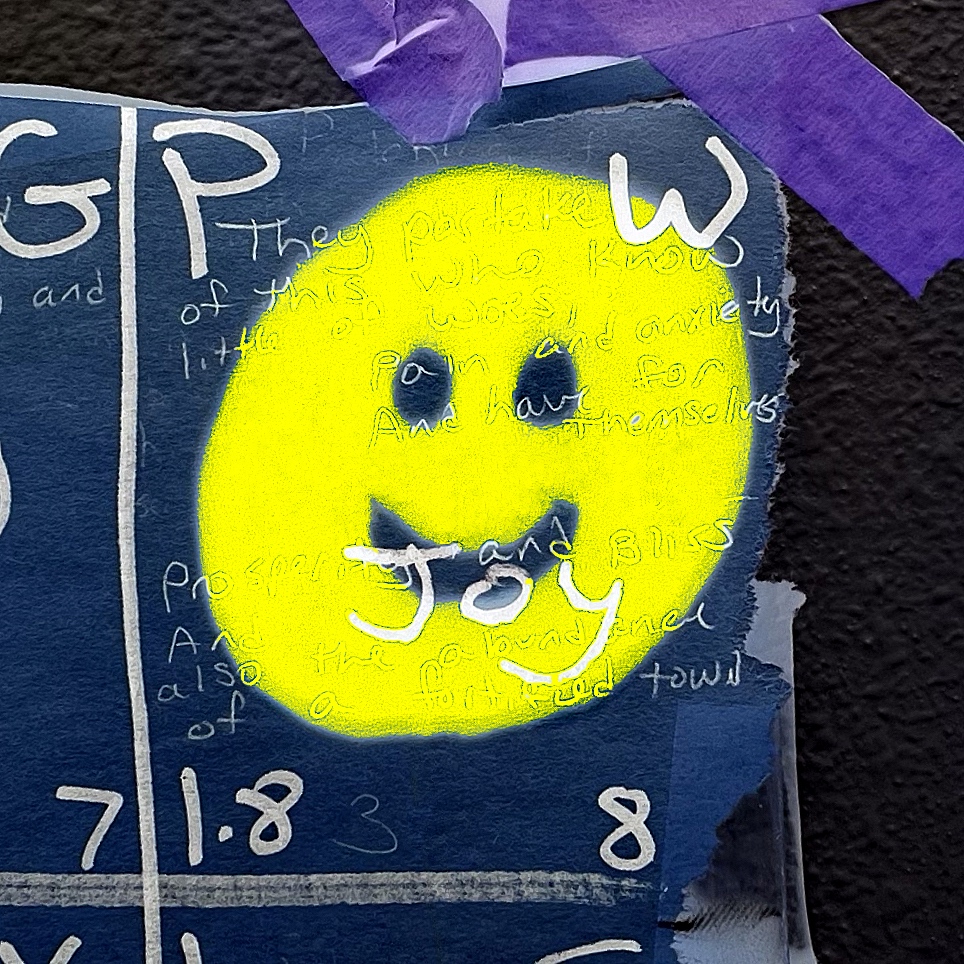

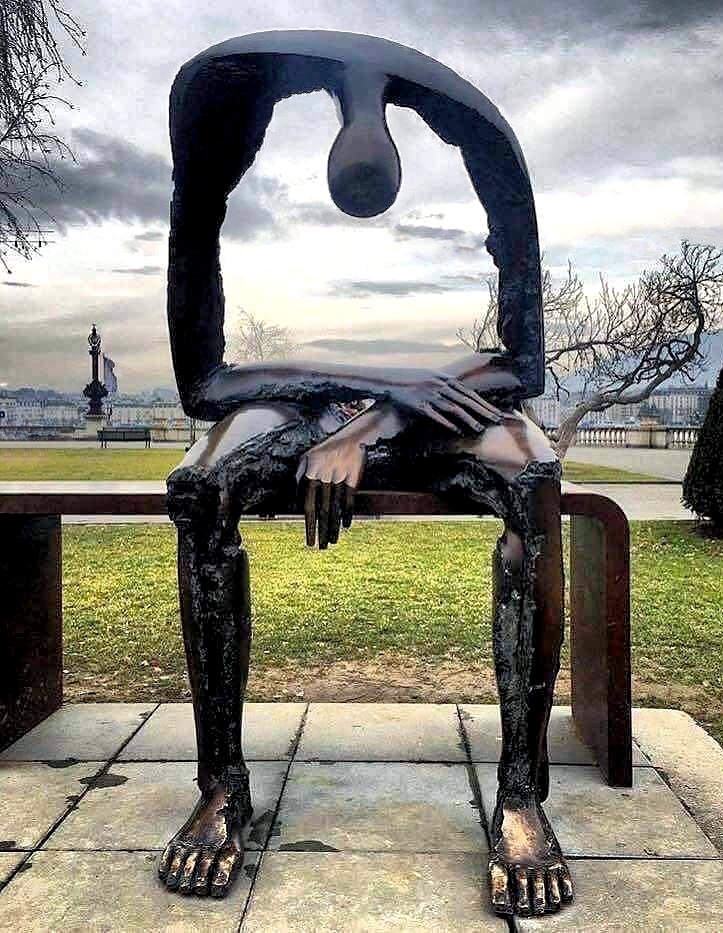

You ok? You look a mess. Well, you knew this meltdown was coming. We all did. There were signals and patterns and that was a massive red flag back there, but no. Some people don’t listen. Well, don’t just stand there looking at everybody else’s better deal, you need to pay attention now before the next thing grabs you, and it will grab you.

You ok? You look a mess. Well, you knew this meltdown was coming. We all did. There were signals and patterns and that was a massive red flag back there, but no. Some people don’t listen. Well, don’t just stand there looking at everybody else’s better deal, you need to pay attention now before the next thing grabs you, and it will grab you. Your hand hurts. Your non-ergonomically correct work station is giving you all kinds of scoliosis. You are low on ink and

Your hand hurts. Your non-ergonomically correct work station is giving you all kinds of scoliosis. You are low on ink and

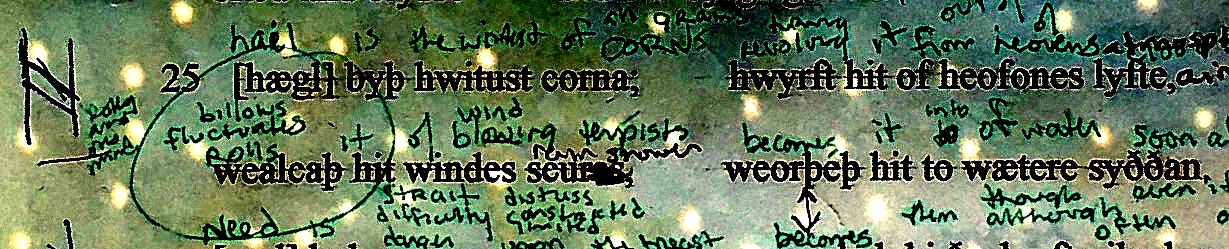

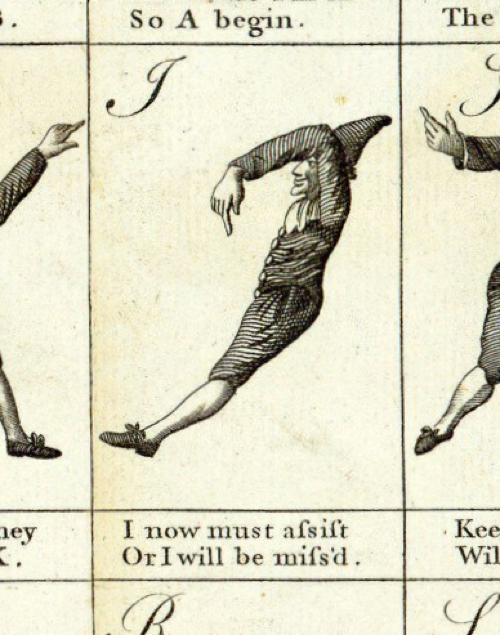

The Rune Poem stanzas

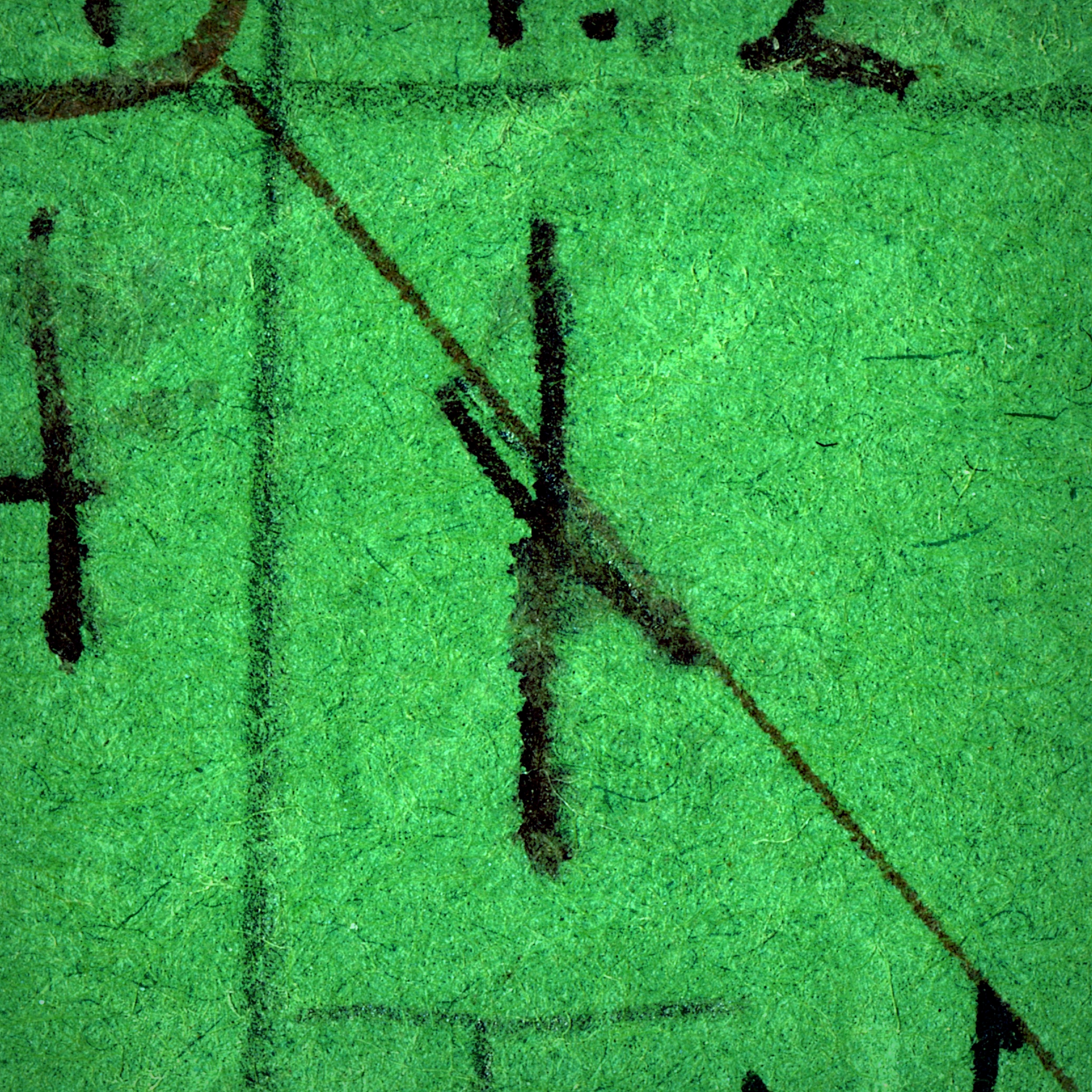

The Rune Poem stanzas  Voiced alveolar nasal. Vibrate some air through your vocal cords, stop it at the roof of your mouth with your tongue. Nope. No passage here. Never. Send that air out through your nose.

Voiced alveolar nasal. Vibrate some air through your vocal cords, stop it at the roof of your mouth with your tongue. Nope. No passage here. Never. Send that air out through your nose. Send out some air and impede it a bit with your vocal cords, press your lips together and

Send out some air and impede it a bit with your vocal cords, press your lips together and

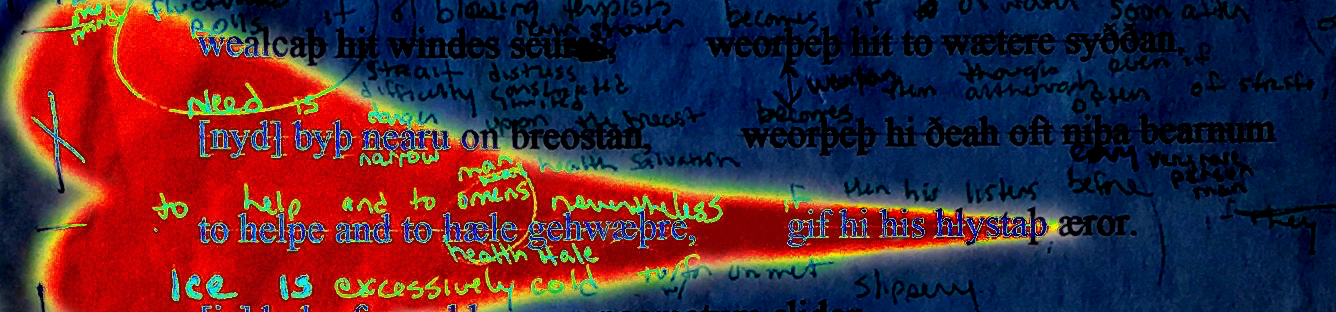

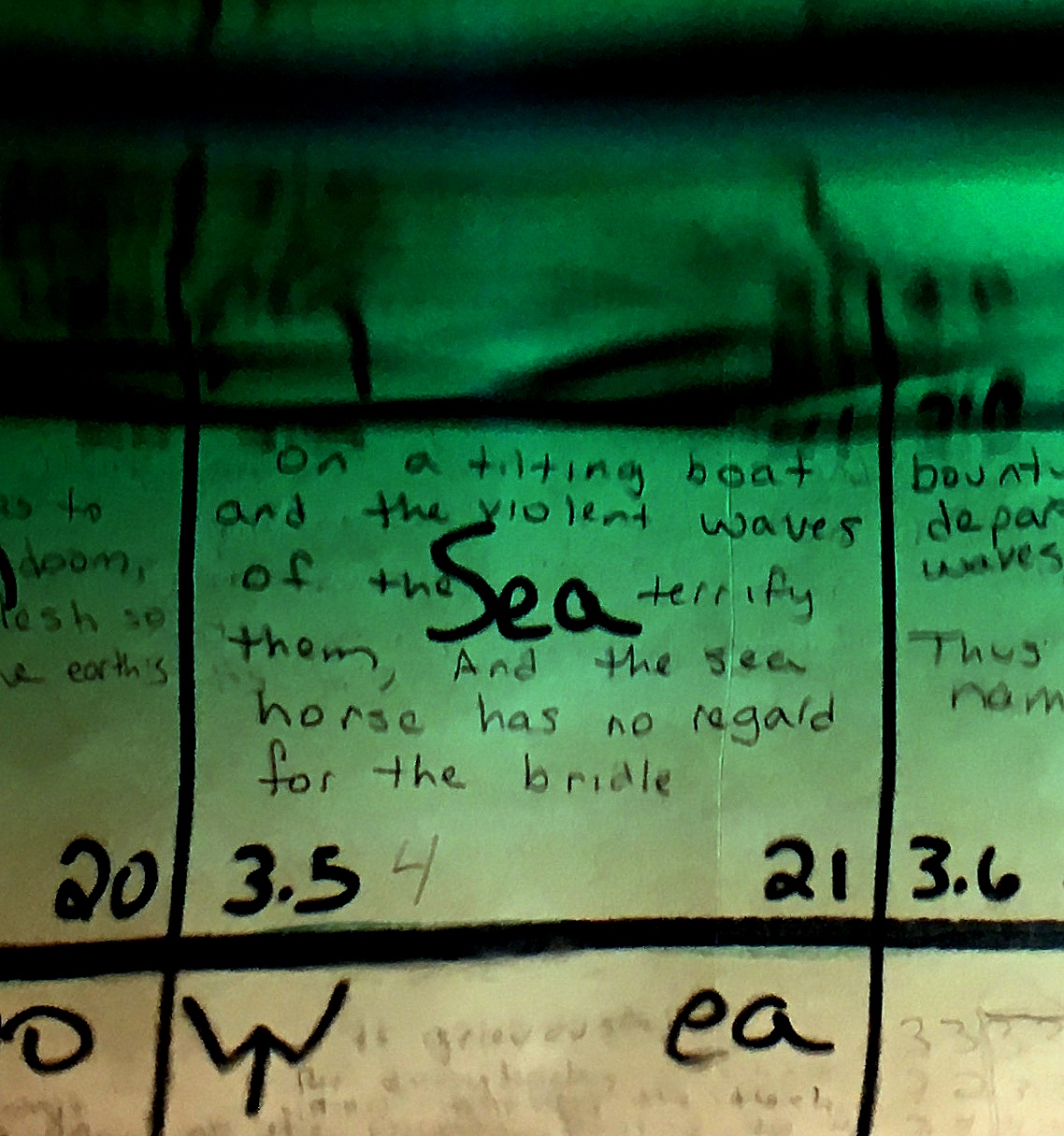

The Rune Poem’s stanzas vary in length. Each of the first eight stanzas consist of three lines containing four beats of stressed syllables: twelve beats total. Then we get an abrupt shift toward brevity with a pair side by side,

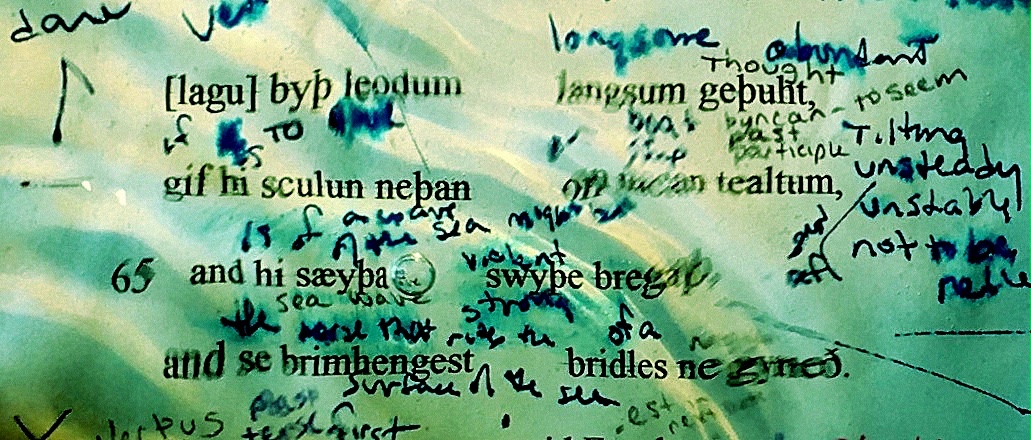

The Rune Poem’s stanzas vary in length. Each of the first eight stanzas consist of three lines containing four beats of stressed syllables: twelve beats total. Then we get an abrupt shift toward brevity with a pair side by side,  Waterways were busy places during the time of the Rune Poem, making for convenient connections between coastal settlements and with ports of trade farther afield. However, things become a lot less easy when

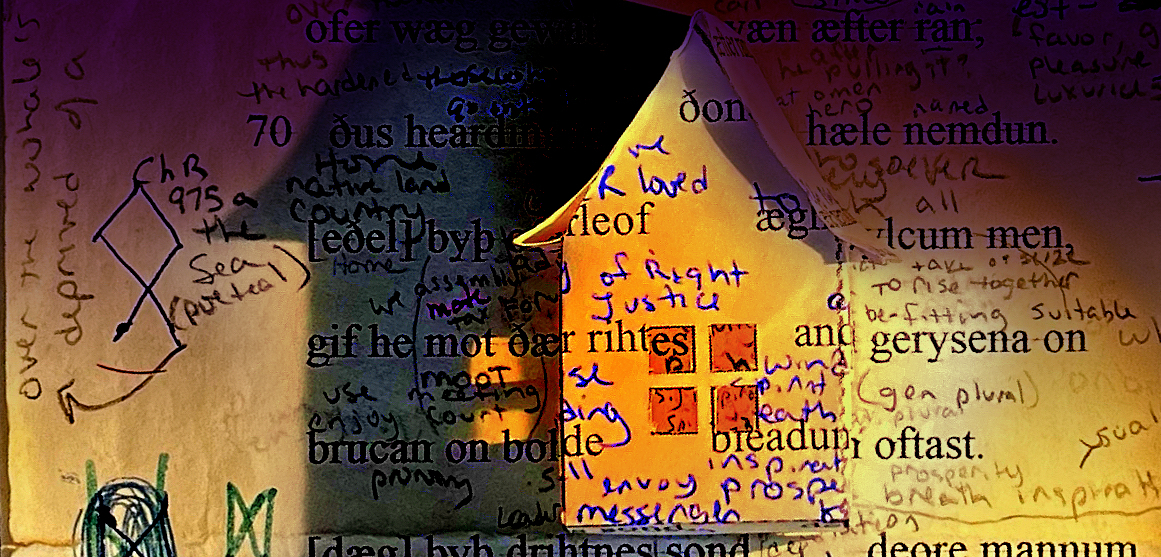

Waterways were busy places during the time of the Rune Poem, making for convenient connections between coastal settlements and with ports of trade farther afield. However, things become a lot less easy when  The people of the Rune Poem were farmers and seafarers living in a wet country, and they had a much closer relationship with weather than we have. We can spend whole productive lives indoors, deep indoors, climate controlled, insulated, where rain cannot penetrate, and we might wonder sometimes is it windy outside? The Rune Poem singers did not need to go outside to find out: they felt the wind in their homes and their bones. Their houses were much more porous, and if the wind wants to send

The people of the Rune Poem were farmers and seafarers living in a wet country, and they had a much closer relationship with weather than we have. We can spend whole productive lives indoors, deep indoors, climate controlled, insulated, where rain cannot penetrate, and we might wonder sometimes is it windy outside? The Rune Poem singers did not need to go outside to find out: they felt the wind in their homes and their bones. Their houses were much more porous, and if the wind wants to send

Voiceless spirant. Make a narrow aperture of your mouth and throat, leave your vocal cords aside, and force air through. Create friction, steam up the mirror. Huh. Hah.

Voiceless spirant. Make a narrow aperture of your mouth and throat, leave your vocal cords aside, and force air through. Create friction, steam up the mirror. Huh. Hah. Alveolar dental sonorant: using your gum ridge and teeth, leave your tongue free laterally, partially impeding your vocal resonance: now sing. Lalalalalalalahhhhh! Largo! Lalalaaaaaaaaah! Now lento. La. La. La. Lovely. A sound so popular it has remained unchanged all this time.

Alveolar dental sonorant: using your gum ridge and teeth, leave your tongue free laterally, partially impeding your vocal resonance: now sing. Lalalalalalalahhhhh! Largo! Lalalaaaaaaaaah! Now lento. La. La. La. Lovely. A sound so popular it has remained unchanged all this time.

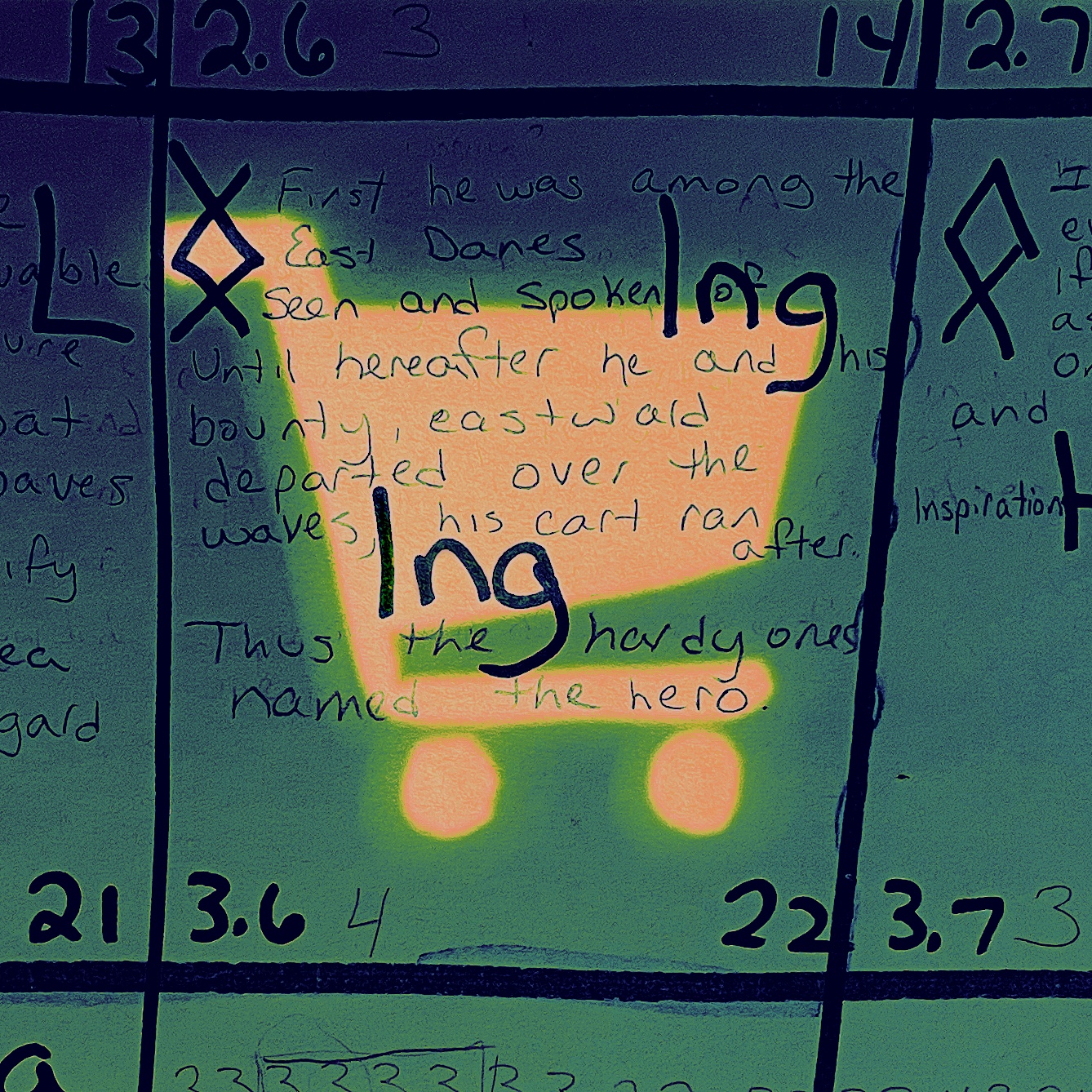

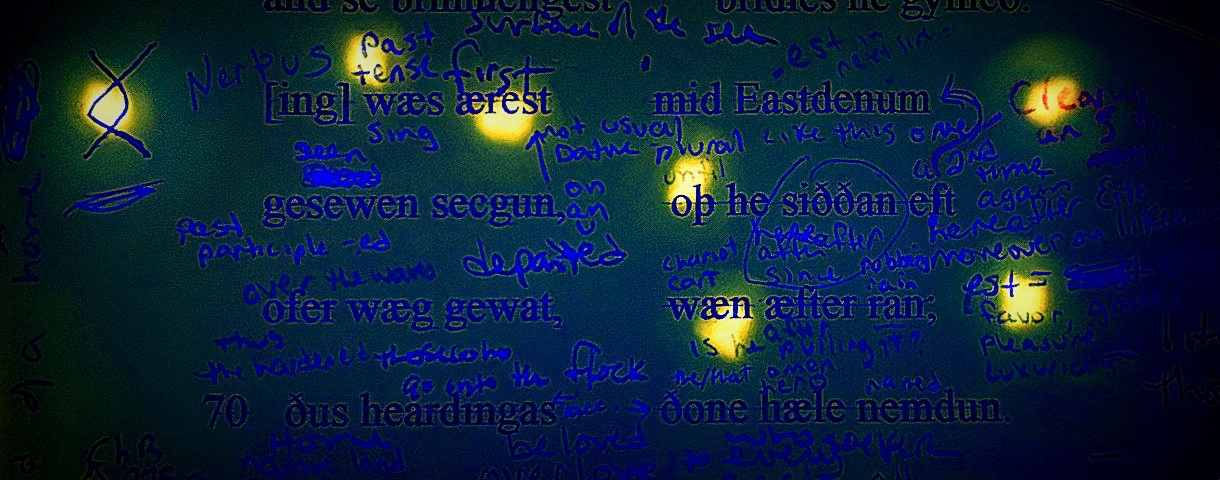

Ing is a mystery. Who is Ing? Where did he go? Why did he leave? We don’t know. You know who knows?

Ing is a mystery. Who is Ing? Where did he go? Why did he leave? We don’t know. You know who knows?

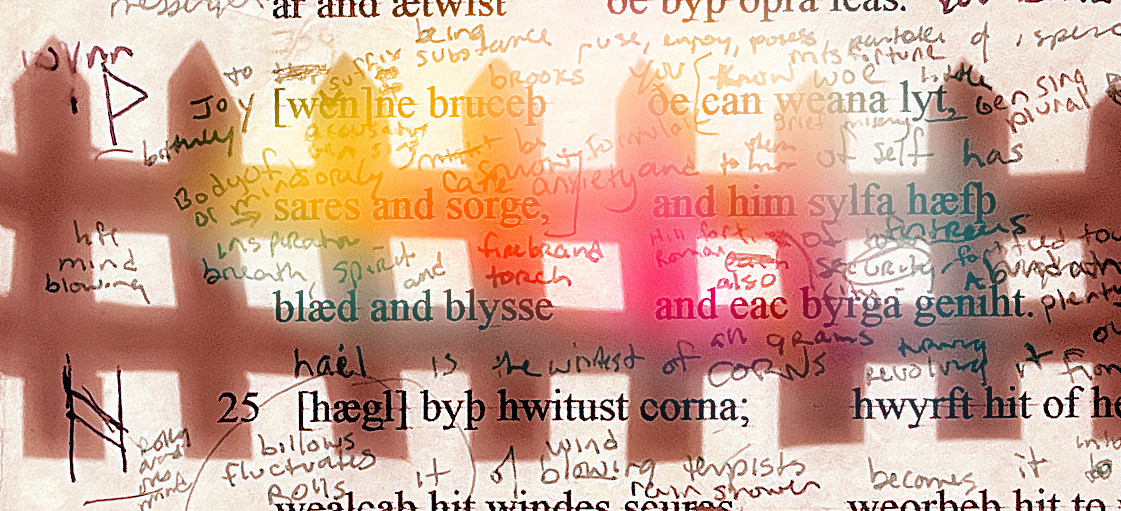

When you line up the Rune Poem stanzas and bend the line back on itself into a long U shape so the runes face each other, you get fourteen pairs. This pair, Ing and Wyn, the eighth, begins the middle half of the poem, moving toward

When you line up the Rune Poem stanzas and bend the line back on itself into a long U shape so the runes face each other, you get fourteen pairs. This pair, Ing and Wyn, the eighth, begins the middle half of the poem, moving toward  What is W? It looks like two Vs but its name says it is U doubled. It is a consonant, but in other times in select places, it is a vowel. What happened? Why do we have W?

What is W? It looks like two Vs but its name says it is U doubled. It is a consonant, but in other times in select places, it is a vowel. What happened? Why do we have W?

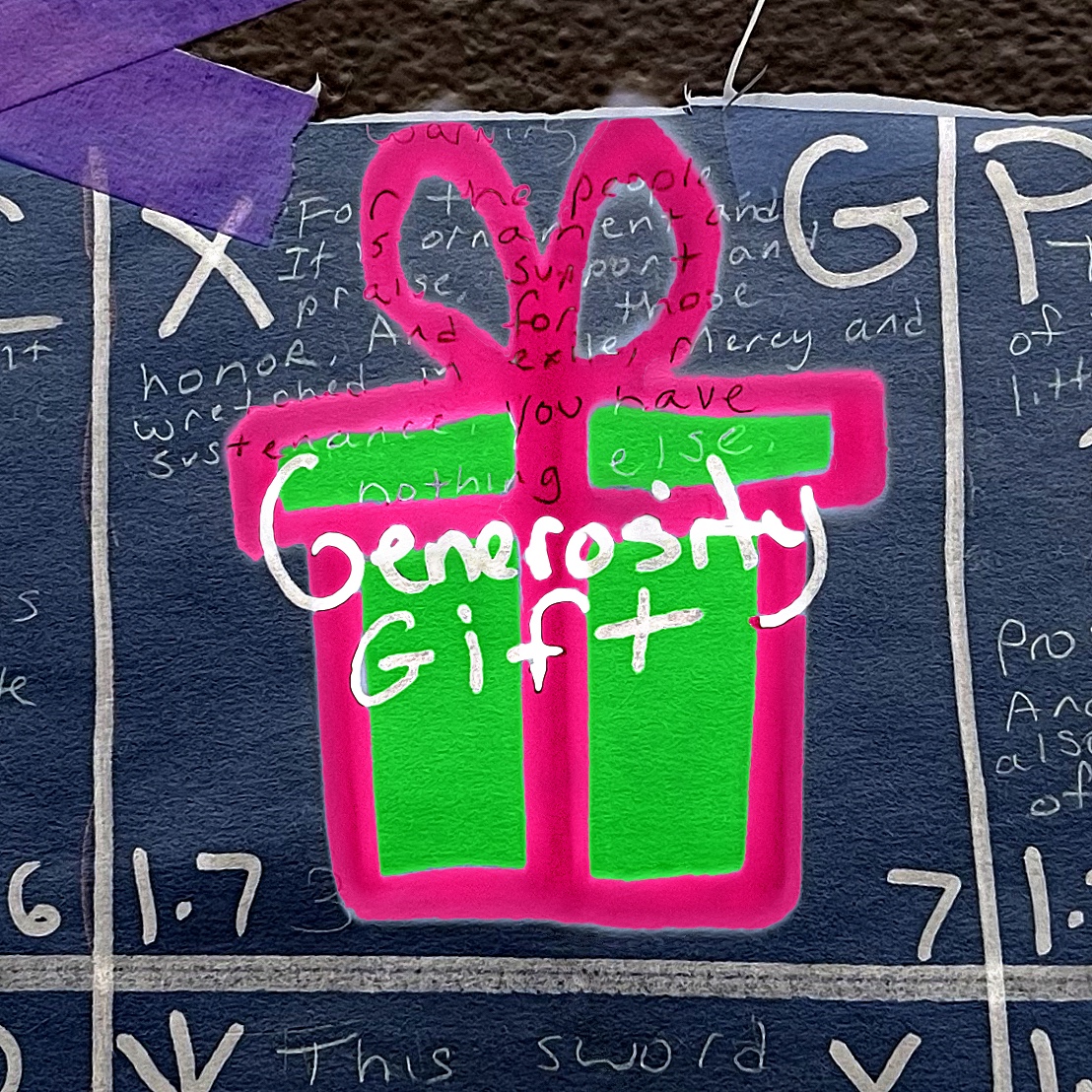

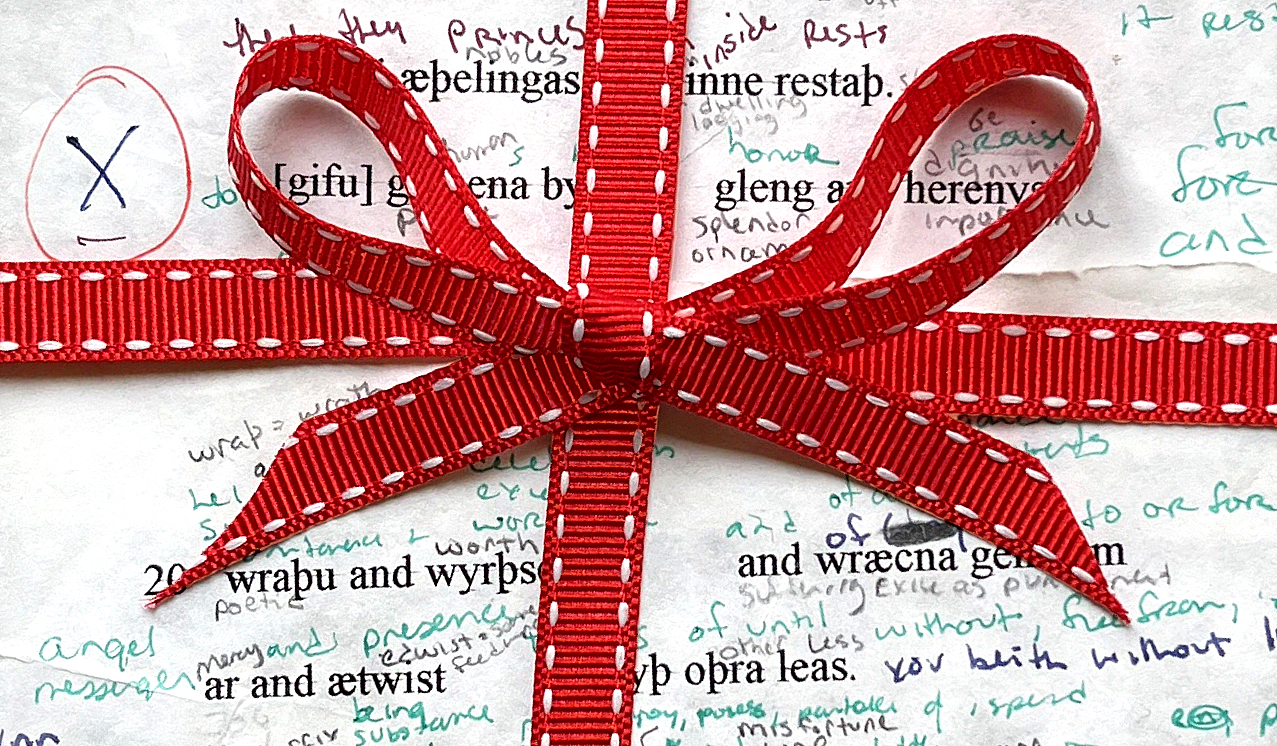

Gift giving was a big deal to the people of the Rune Poem. It was everything. They gave everything. It could be food or goods, but they loved ornament and anything old especially: gilded, edged with silver, blinding shiny, these were the best gifts, but it wasn’t about the bling so much as the message. What you give is what you’re worth and what you will be remembered for. Everybody wants to be worth something and everybody wants to be remembered, it’s the only permanent thing in a world

Gift giving was a big deal to the people of the Rune Poem. It was everything. They gave everything. It could be food or goods, but they loved ornament and anything old especially: gilded, edged with silver, blinding shiny, these were the best gifts, but it wasn’t about the bling so much as the message. What you give is what you’re worth and what you will be remembered for. Everybody wants to be worth something and everybody wants to be remembered, it’s the only permanent thing in a world  The Rune Poem is sung in a tempo that changes from time to time. You can find the beats and the rests between them in the stresses of the words in each stanza. Some move quickly like the adjacent

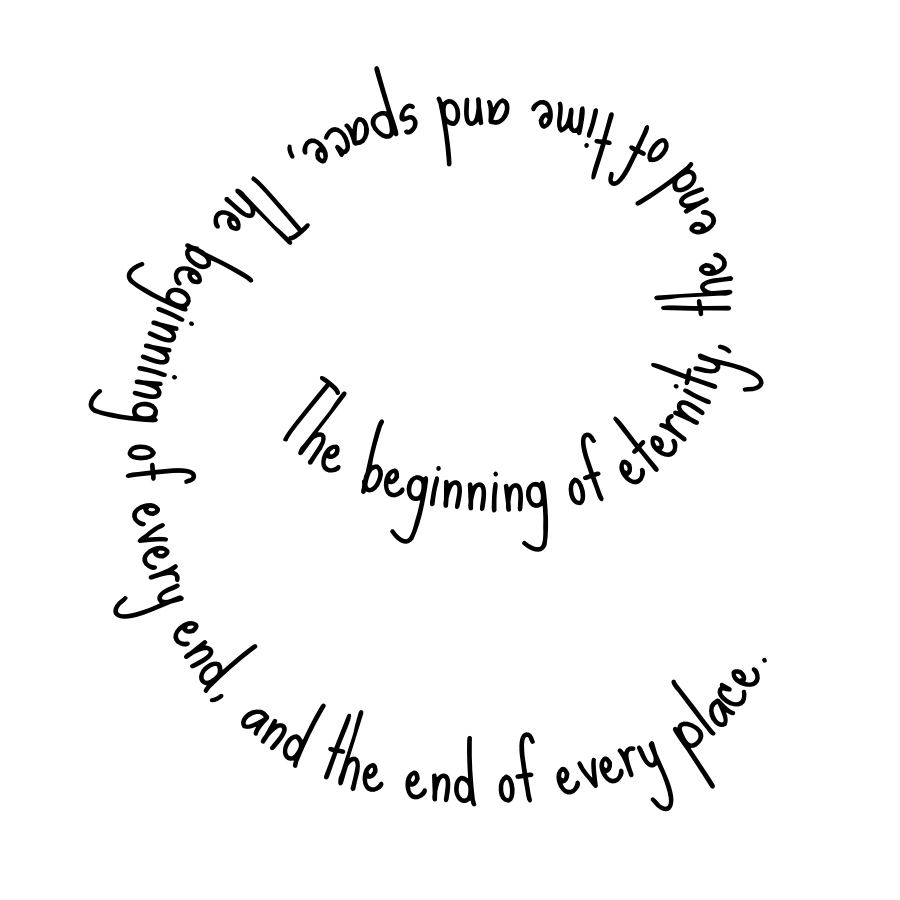

The Rune Poem is sung in a tempo that changes from time to time. You can find the beats and the rests between them in the stresses of the words in each stanza. Some move quickly like the adjacent  You possess me always but may touch me not,

You possess me always but may touch me not,

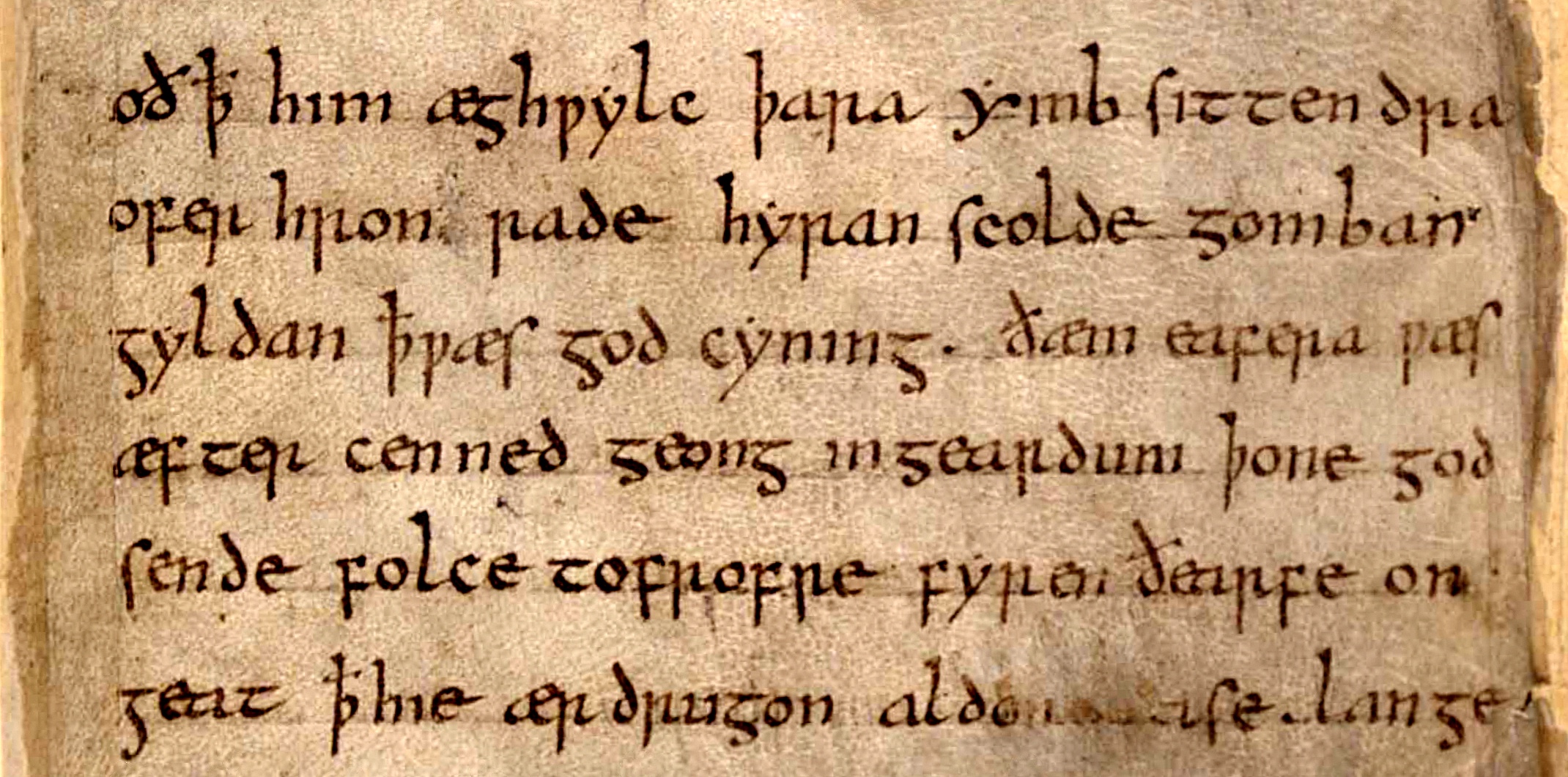

Imagine yourself. Now imagine yourself 1500 years ago. Can you think like that? Think in Old English. There you go. Now you belong to a people who knew the

Imagine yourself. Now imagine yourself 1500 years ago. Can you think like that? Think in Old English. There you go. Now you belong to a people who knew the  I sing this wretched song, my full sorrow

I sing this wretched song, my full sorrow