H: At the start of an Old English word, H is almost silent, an H on its way out. Hha. A burst of breath in cold air, watch it freeze.

H: At the start of an Old English word, H is almost silent, an H on its way out. Hha. A burst of breath in cold air, watch it freeze.

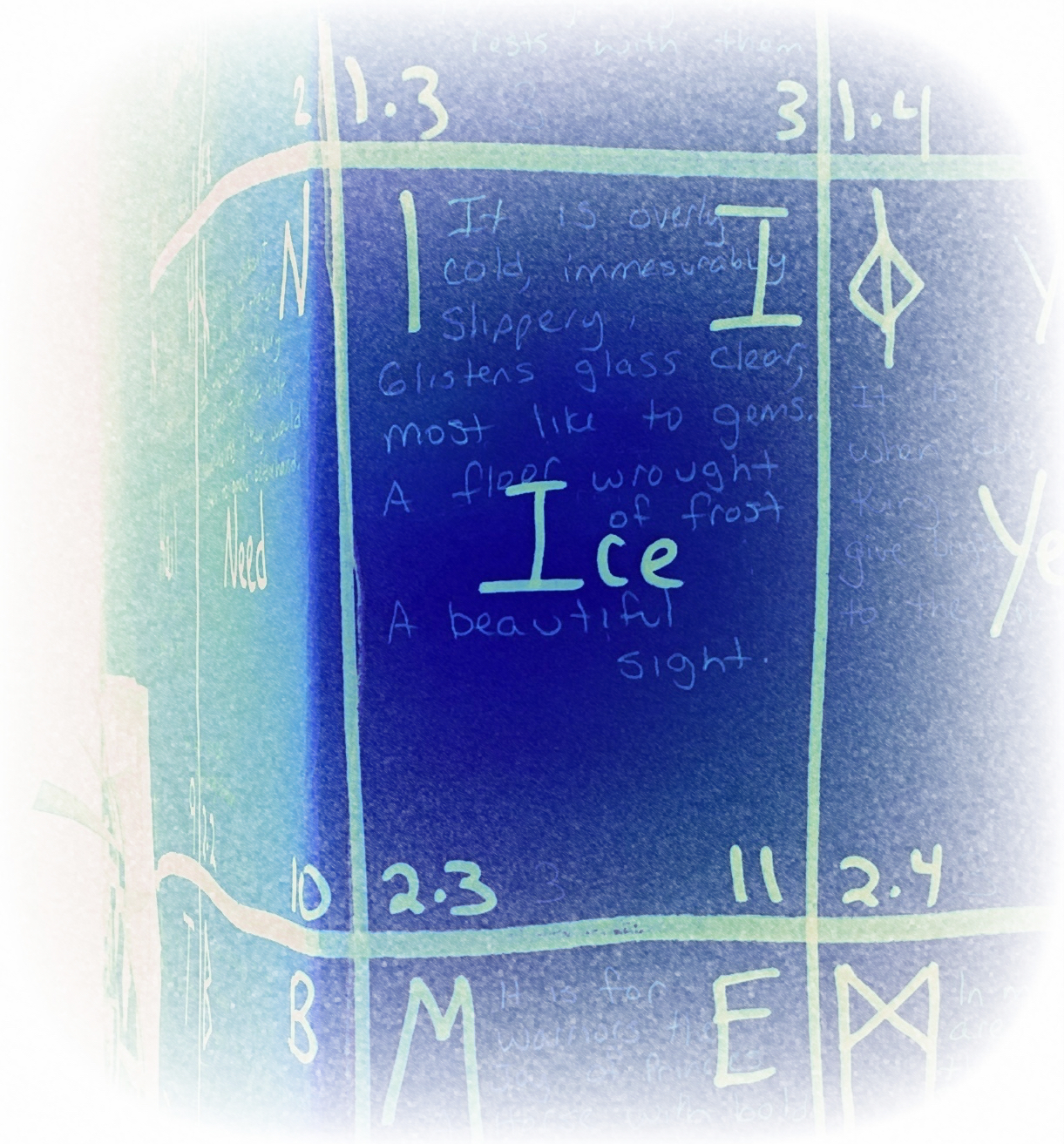

I: Short vowel. Hint and hinge and hinder.

L: Hill.

D: Duh.

E: Short. Death, dead, desecrate.

G: In front of a short I, palatalized (fronted, front of the mouth). Sounds like Y. Yield.

I: Short.

C: Between a short I and a short E, a K sound. Ick. A long I here would make it itch, but what’s going on here is way past itchy. It’s gross.

E: Short. The E in Kenning.

L: Hildegicel. Hild means war, gicel means icicle. A warcicle. A word found only in Beowulf.

King Hroðgar, descendent of Scyld Scylding, deceased, has a massive problem. A moody wight called Grendel is killing people in Hroðgar’s hall. Beowulf, great hero, total legend, hears about this and … More

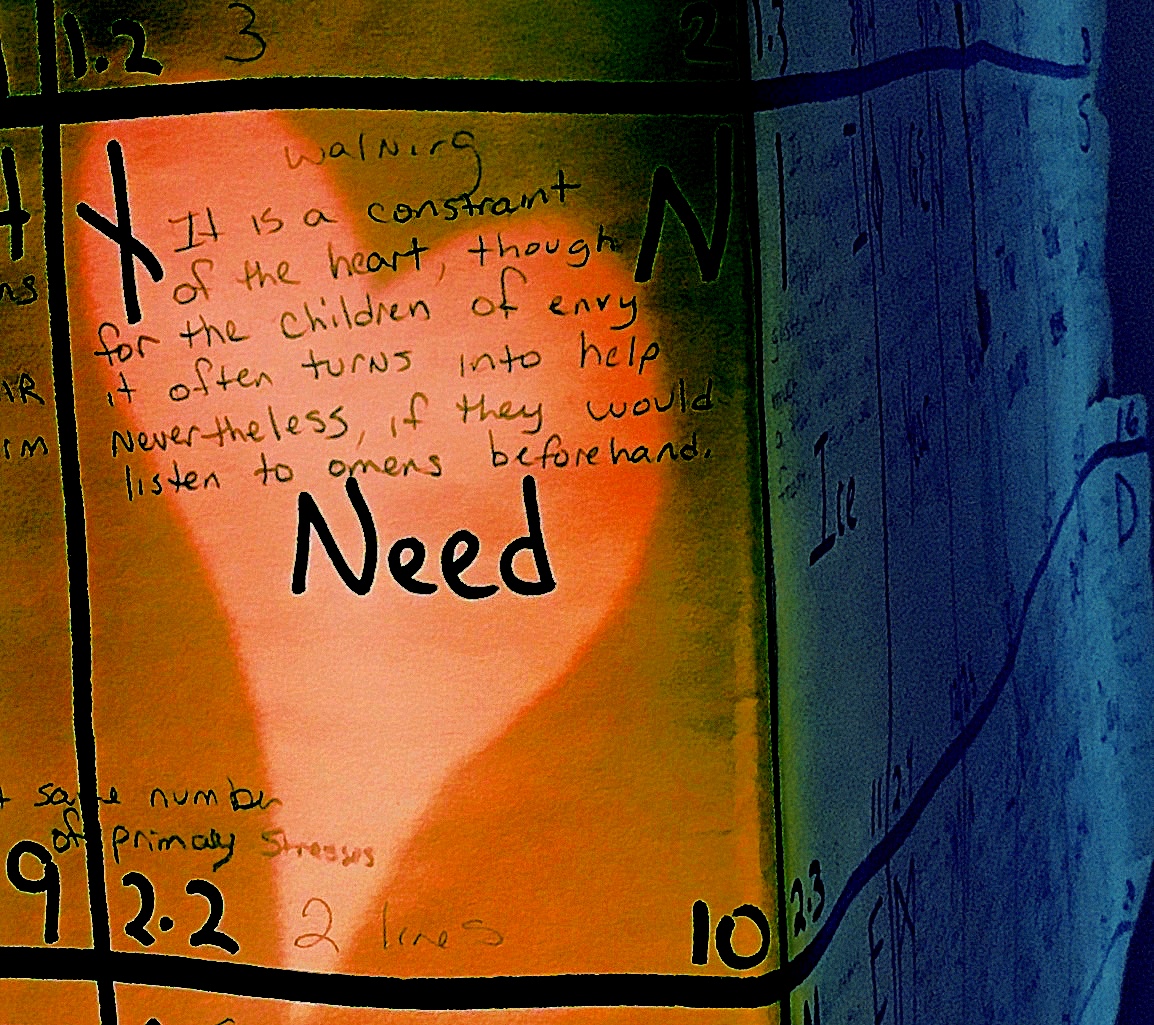

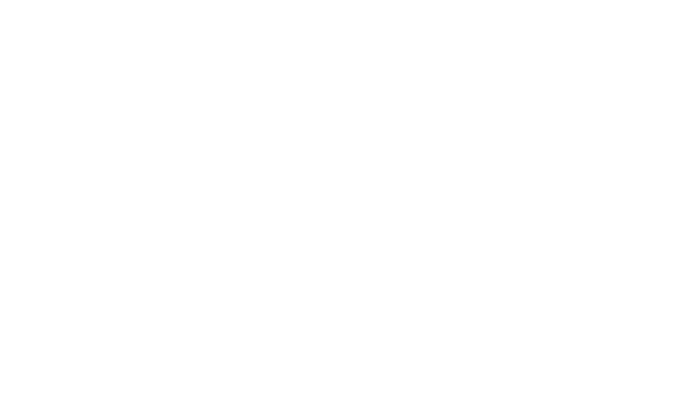

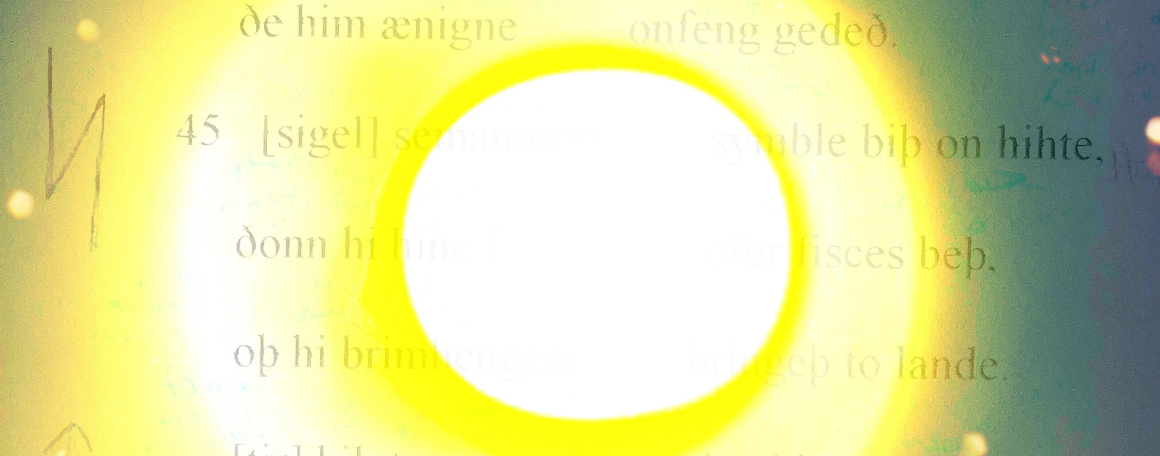

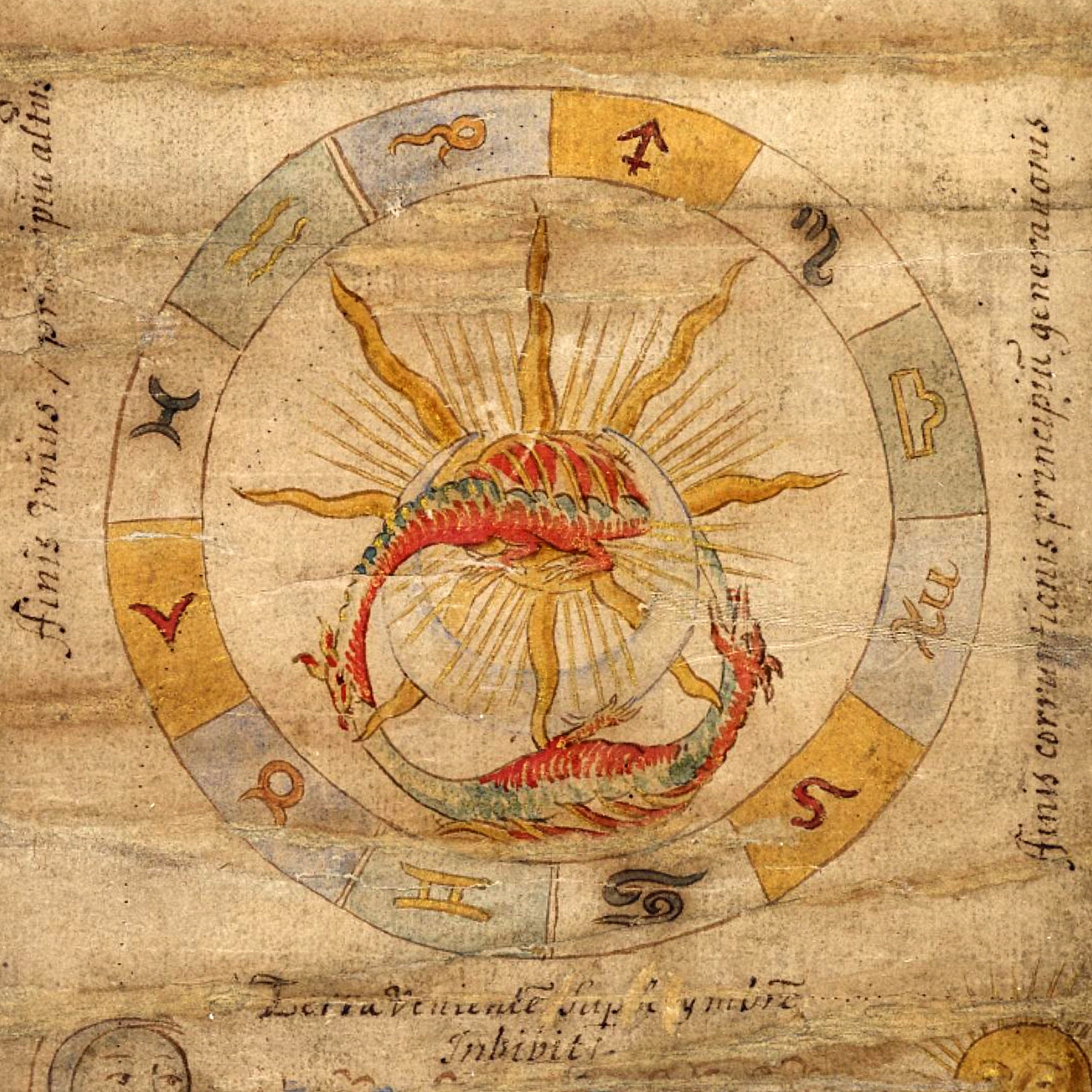

The answer to this stanza riddle is the word eolhx, meaning unclear. We know this is the name of the rune because this word appears in the only copy we have of the Rune Poem, printed in 1705 from the only surviving manuscript copy,

The answer to this stanza riddle is the word eolhx, meaning unclear. We know this is the name of the rune because this word appears in the only copy we have of the Rune Poem, printed in 1705 from the only surviving manuscript copy, Solve for X. X = a stand in for consonant clusters: sounds like ks for word endings and when it appears after stressed vowels. It is an unvoiced ks when it comes before a t, voiced as gz for before stressed vowels, and kzh for the middle of words. It can also sound like Z at the beginning of a word, K in the middle, and sometimes remains silent for word endings. Why such a multiplicity of work for

Solve for X. X = a stand in for consonant clusters: sounds like ks for word endings and when it appears after stressed vowels. It is an unvoiced ks when it comes before a t, voiced as gz for before stressed vowels, and kzh for the middle of words. It can also sound like Z at the beginning of a word, K in the middle, and sometimes remains silent for word endings. Why such a multiplicity of work for

The answer to this riddle is

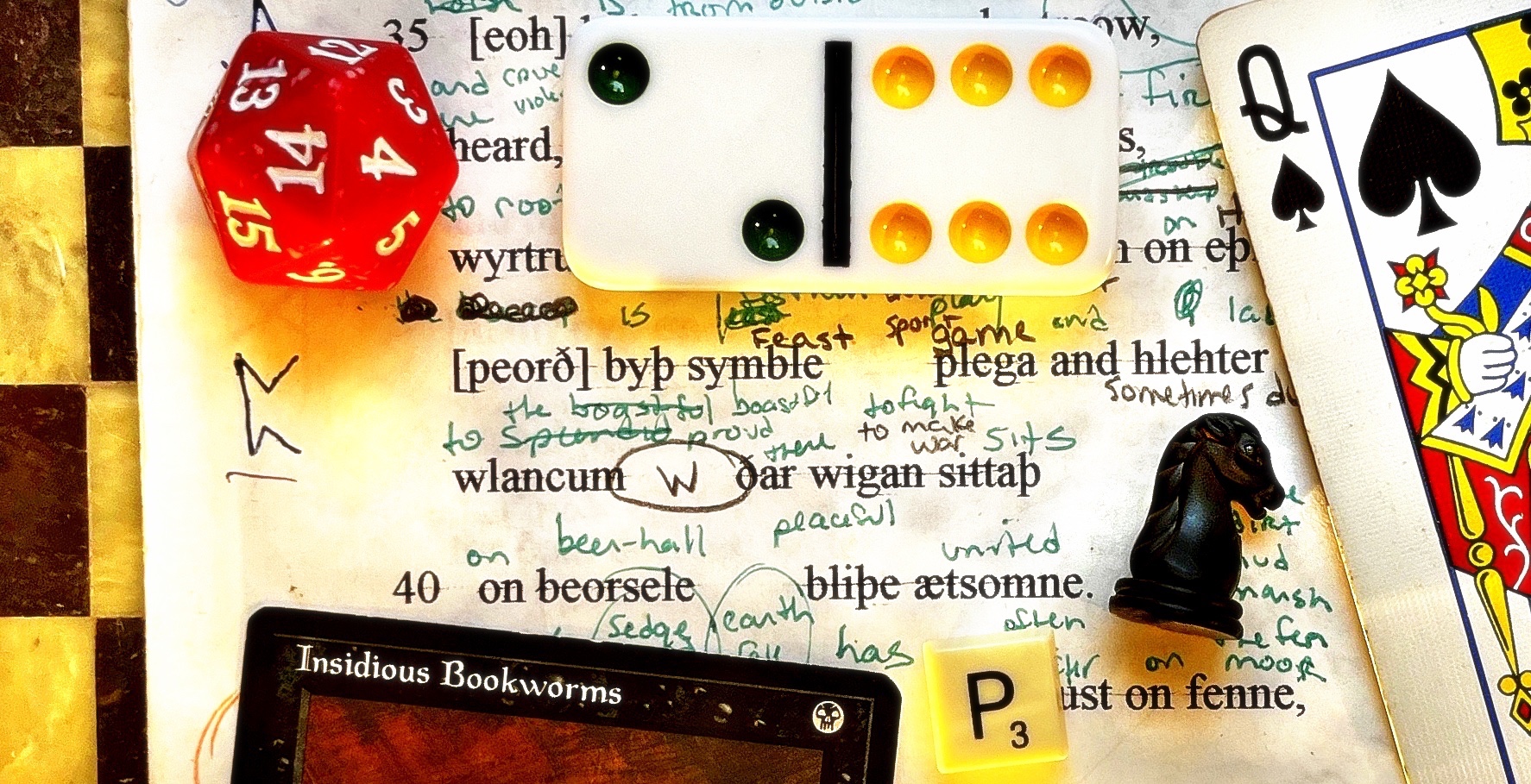

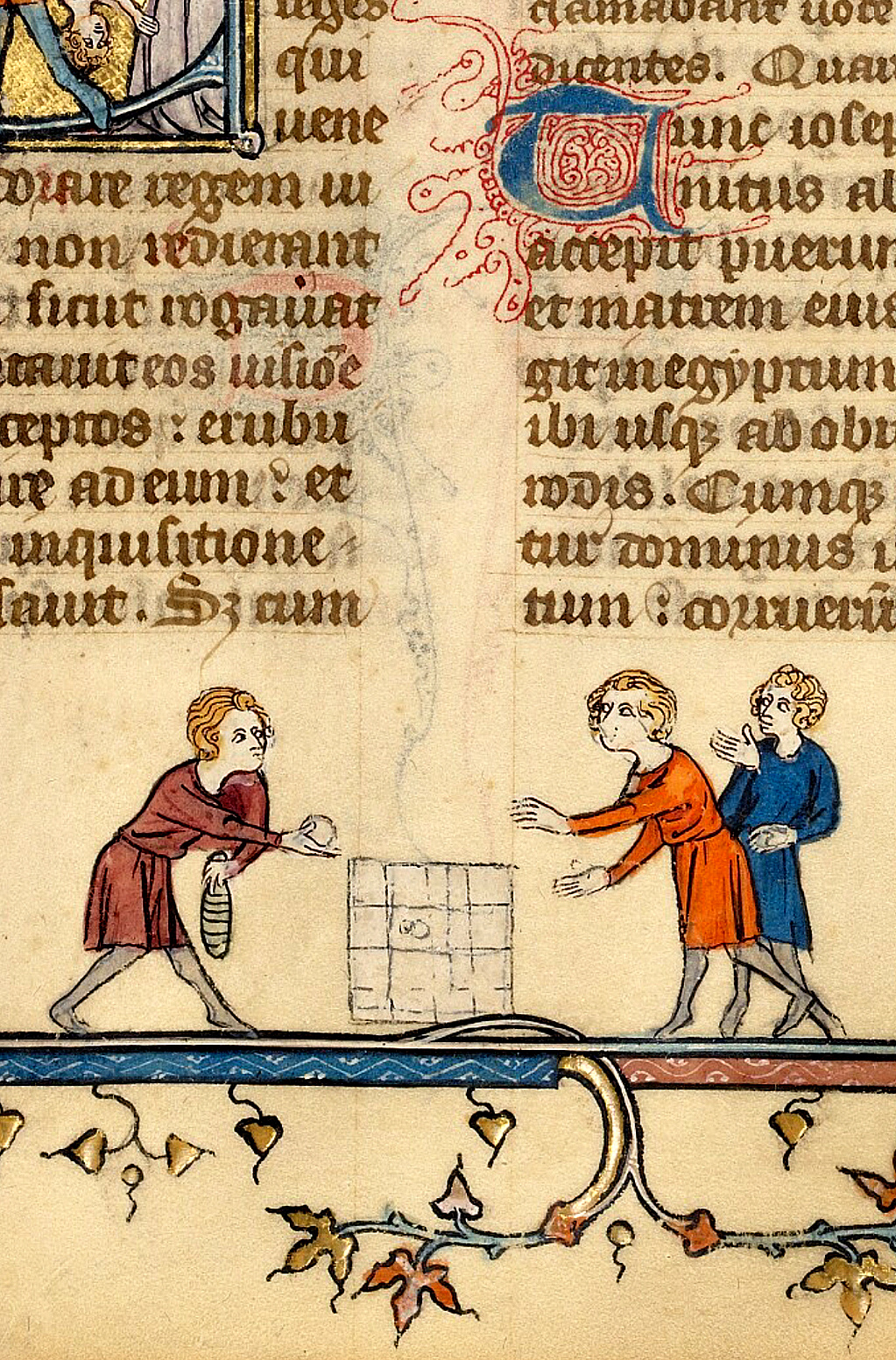

The answer to this riddle is Nobody knows what this is for certain. The only time we ever see the word peorð in Old English is in lists of rune names, so we only know what the Rune Poem riddle says, that

Nobody knows what this is for certain. The only time we ever see the word peorð in Old English is in lists of rune names, so we only know what the Rune Poem riddle says, that

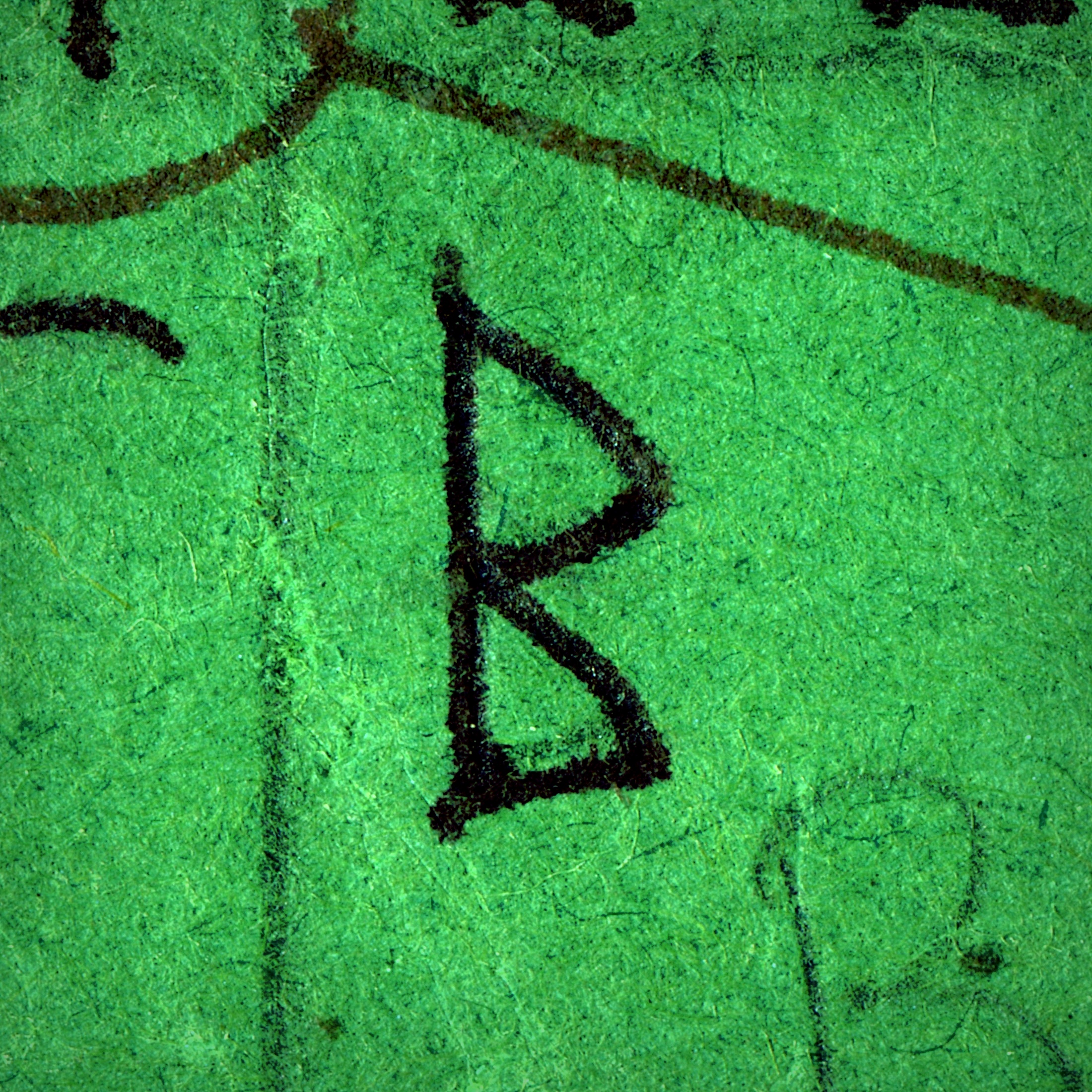

Voiceless bilabial stop. Send air through your mouth, now stop it, now start. If you vibrate your vocal cords you make a B. This is not that, keep your larynx still and put a little extra air into it. Perfect.

Voiceless bilabial stop. Send air through your mouth, now stop it, now start. If you vibrate your vocal cords you make a B. This is not that, keep your larynx still and put a little extra air into it. Perfect.

Alveolar voiceless spirant. Send air into your mouth, almost closed, then slip it out sibilantly. See? Splendid.

Alveolar voiceless spirant. Send air into your mouth, almost closed, then slip it out sibilantly. See? Splendid.

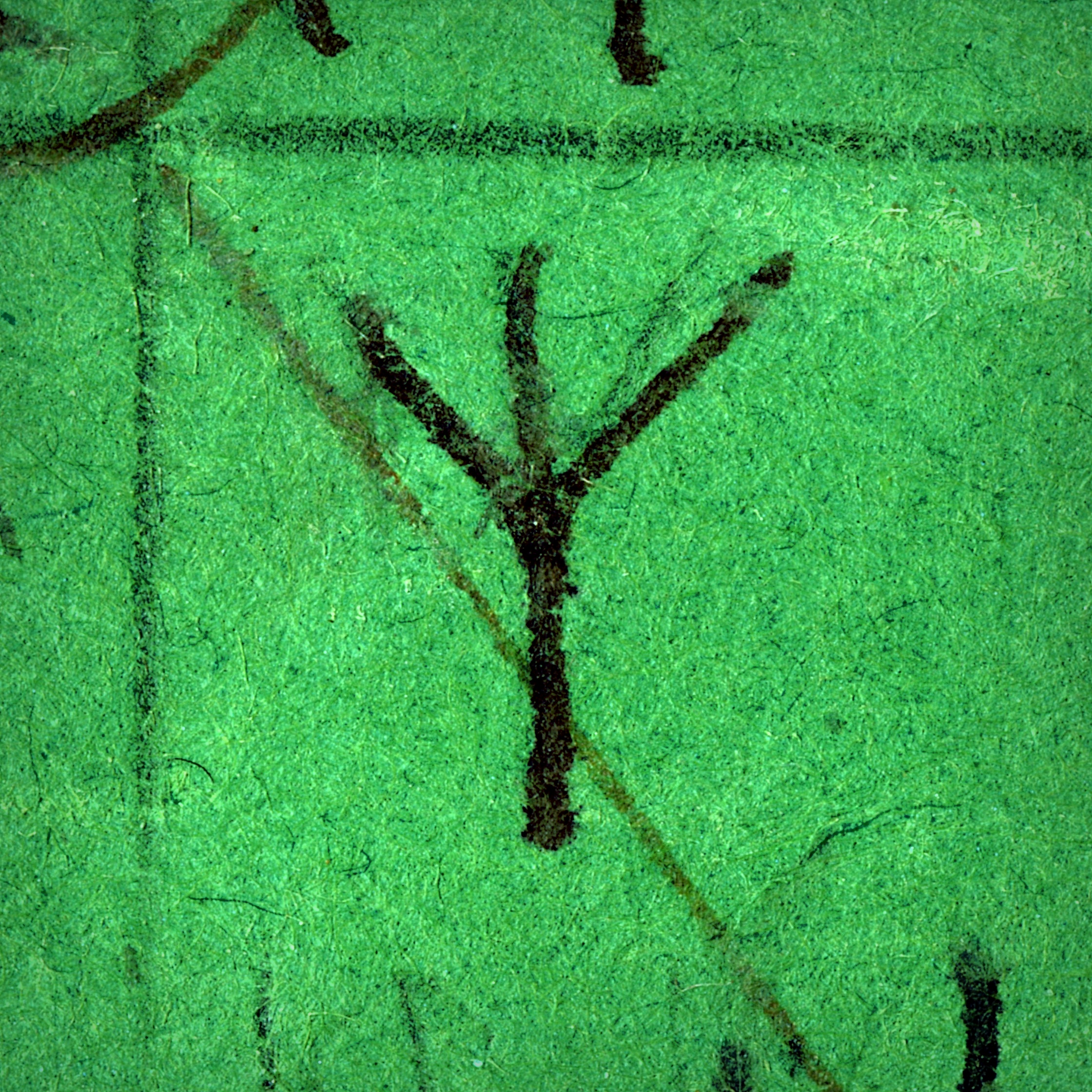

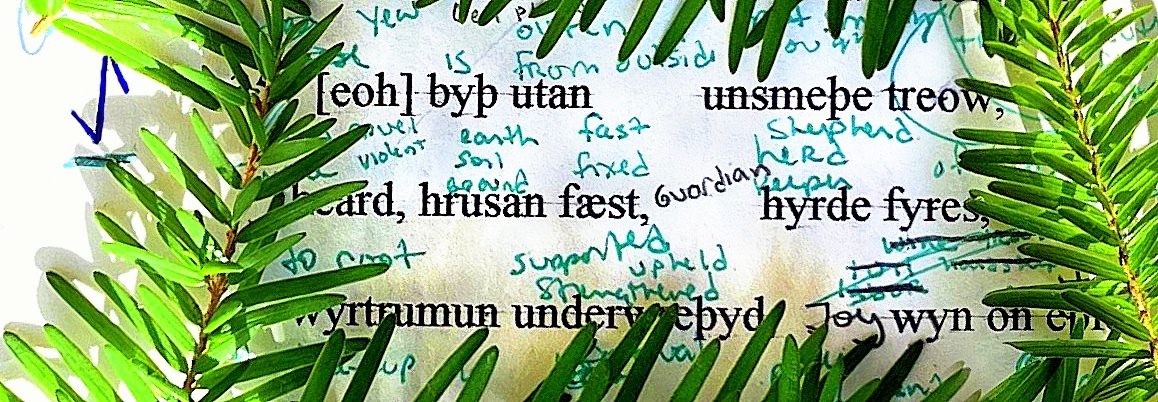

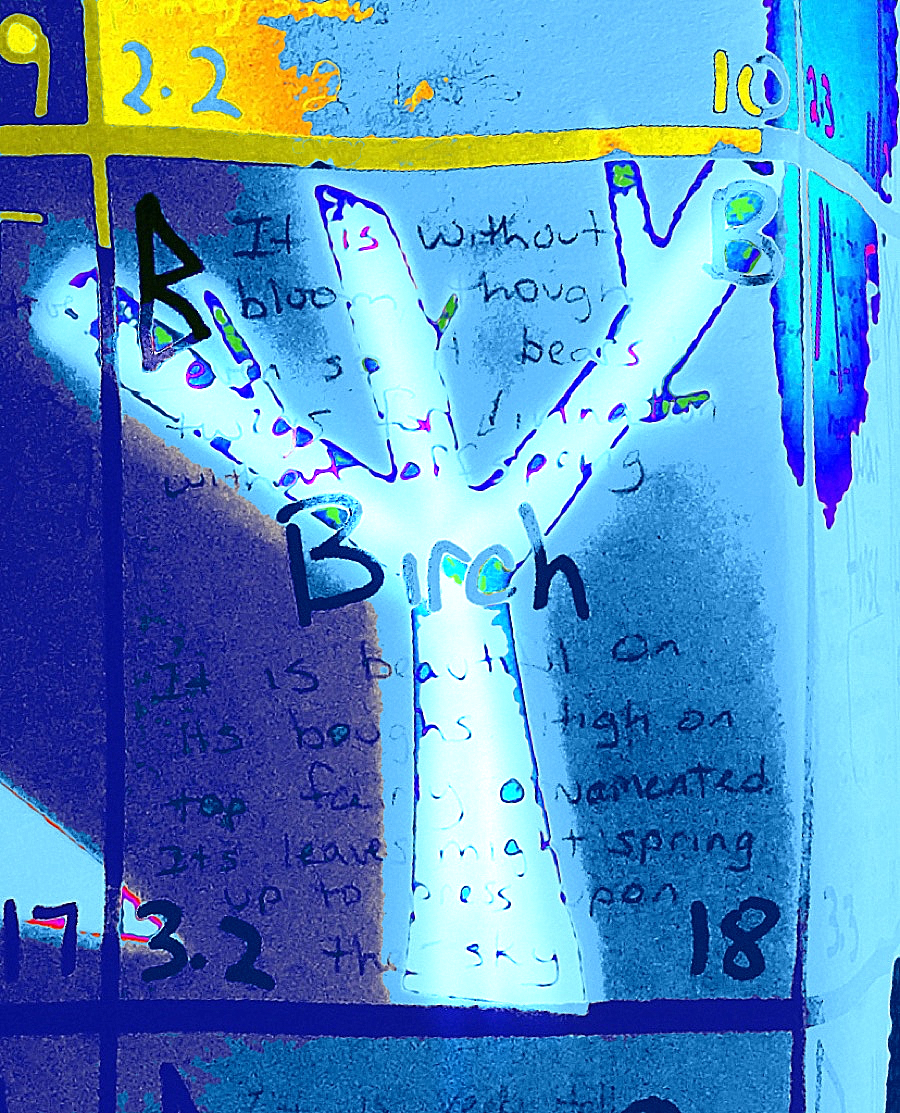

A tree does not show up in the Rune Poem unless it is important. You think they’ll let just any tree grow in these sacred woods? No. These are the god trees. Useful too.

A tree does not show up in the Rune Poem unless it is important. You think they’ll let just any tree grow in these sacred woods? No. These are the god trees. Useful too.

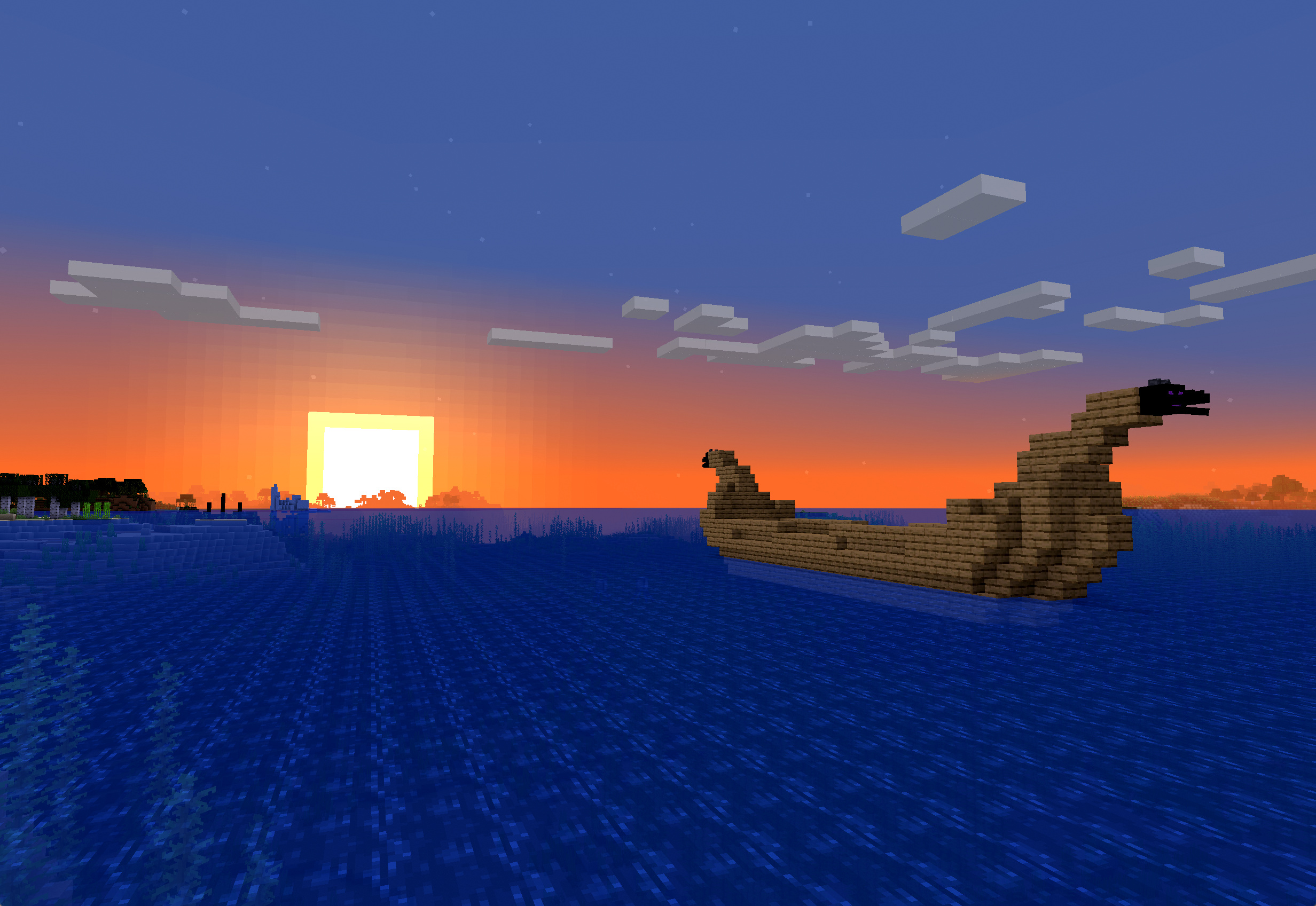

The yew is absolutely massive compared to us, so much weight shooting up, lengthening, drooping back down to plunge into the earth, travel, shoot back up and do it again: swoop up into sky, fall back into earth, swim forward, break through waves into sky and flip back under again. This tree is a fish, moving so slowly through thousands of years in a single life span, we never see it happen. We think the yew stands still. We can trust it will always be there. God knows how the yew sees us. An irritant? An itchy parasite flaring up from time to time? We move so fast we must be itchy.

The yew is absolutely massive compared to us, so much weight shooting up, lengthening, drooping back down to plunge into the earth, travel, shoot back up and do it again: swoop up into sky, fall back into earth, swim forward, break through waves into sky and flip back under again. This tree is a fish, moving so slowly through thousands of years in a single life span, we never see it happen. We think the yew stands still. We can trust it will always be there. God knows how the yew sees us. An irritant? An itchy parasite flaring up from time to time? We move so fast we must be itchy. Alveolar dental: tongue along teeth, gums too. Stop and start the air flow. Let your voice stay out of it.

Alveolar dental: tongue along teeth, gums too. Stop and start the air flow. Let your voice stay out of it.

Short E, mouth a little open: eh, no big deal. Let the E fall off past an O. Let it keep falling, we don’t use these sounds together anymore.

Short E, mouth a little open: eh, no big deal. Let the E fall off past an O. Let it keep falling, we don’t use these sounds together anymore.

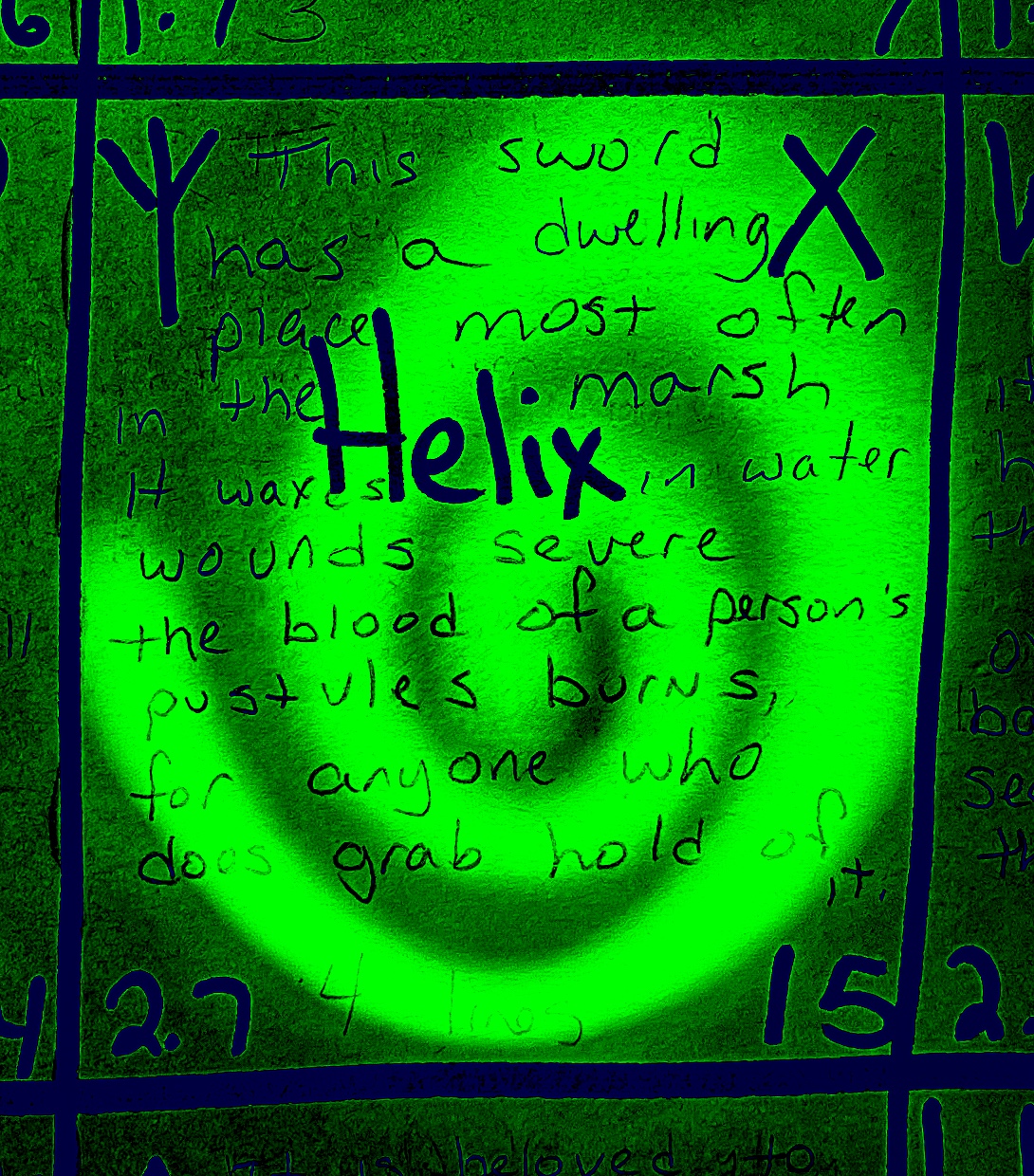

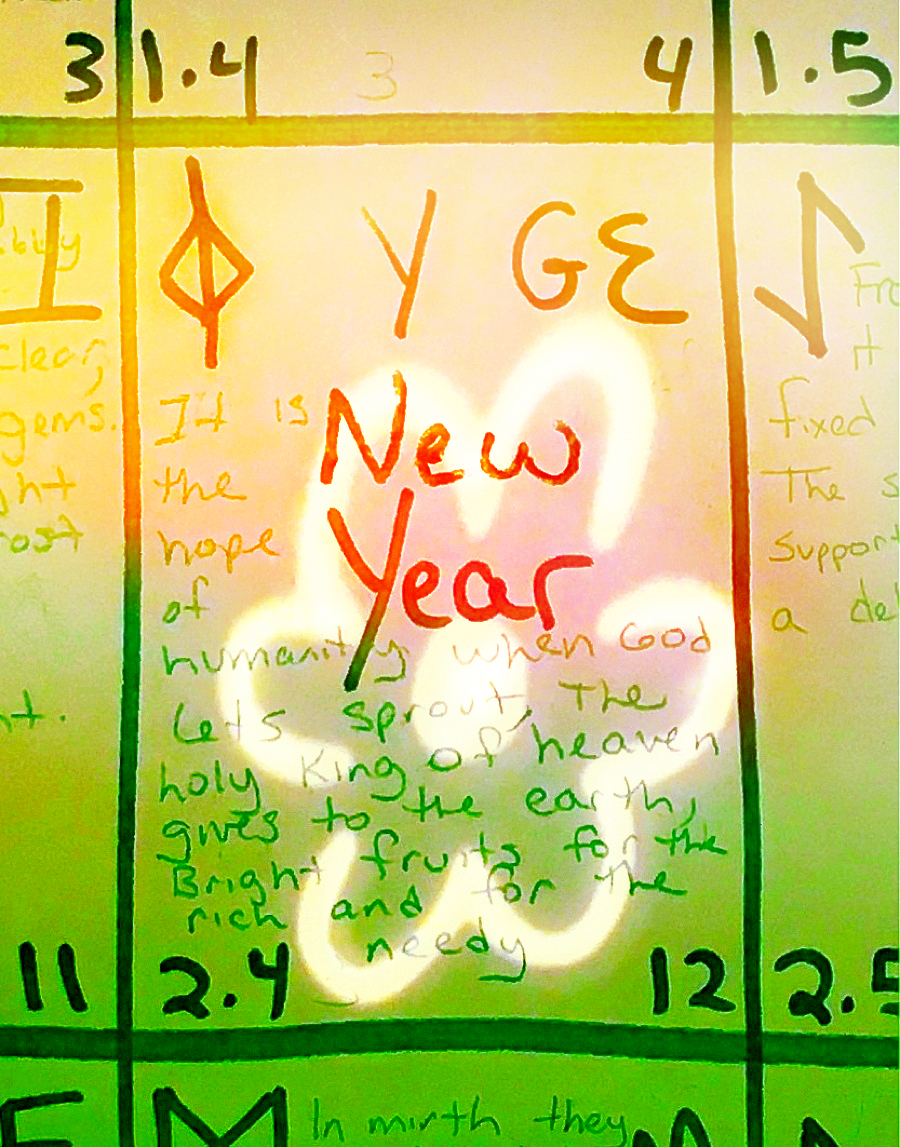

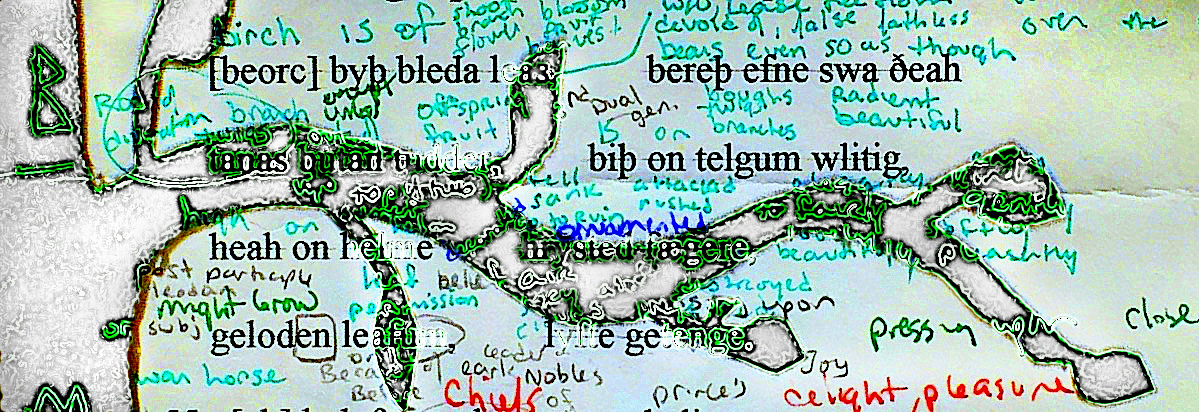

This stanza’s riddle is about a tree. There lives

This stanza’s riddle is about a tree. There lives

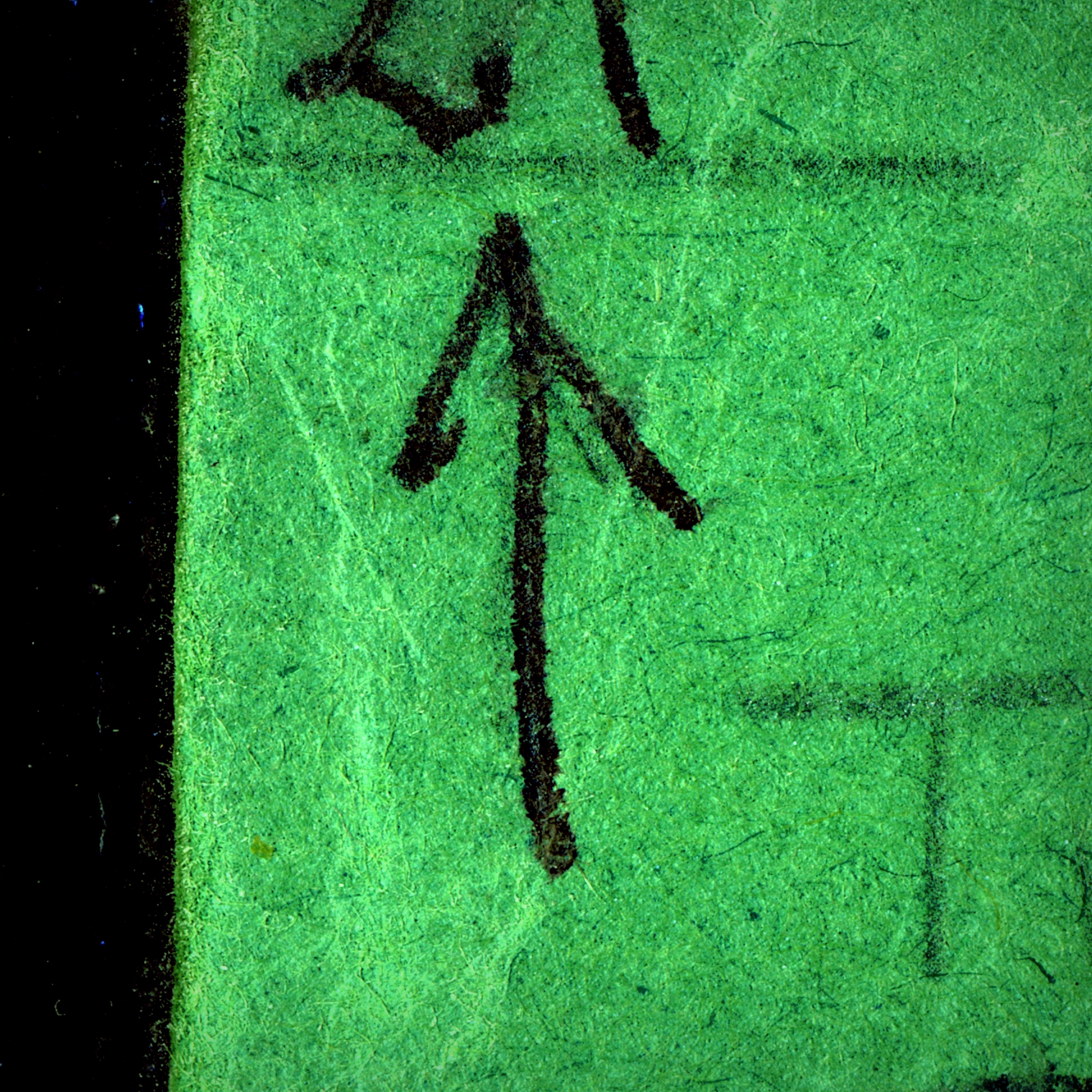

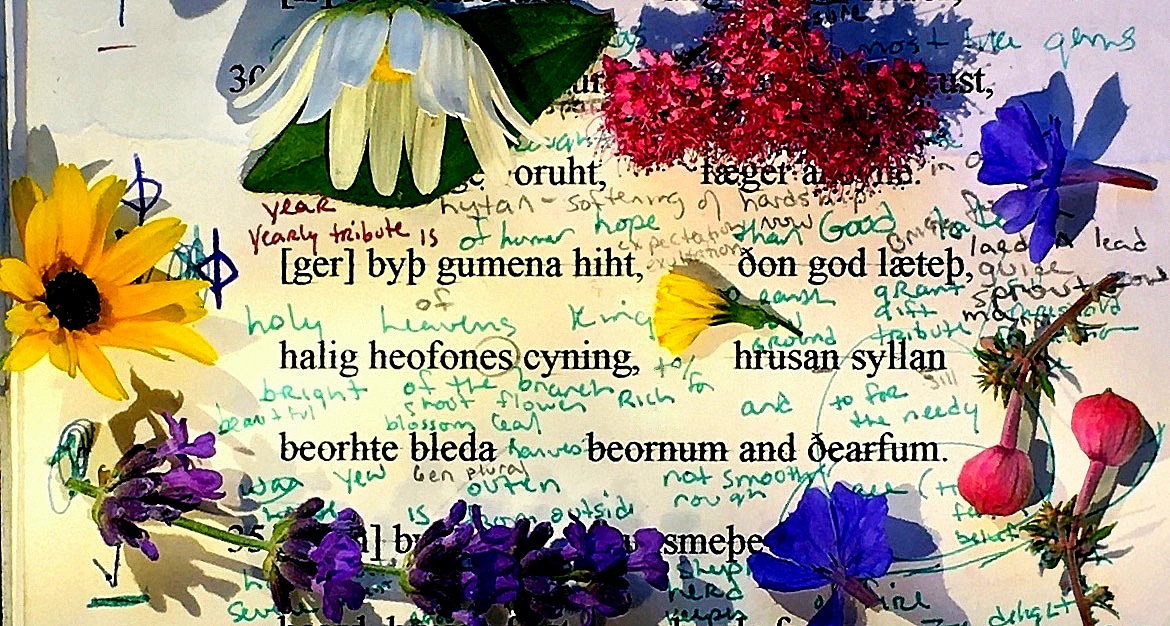

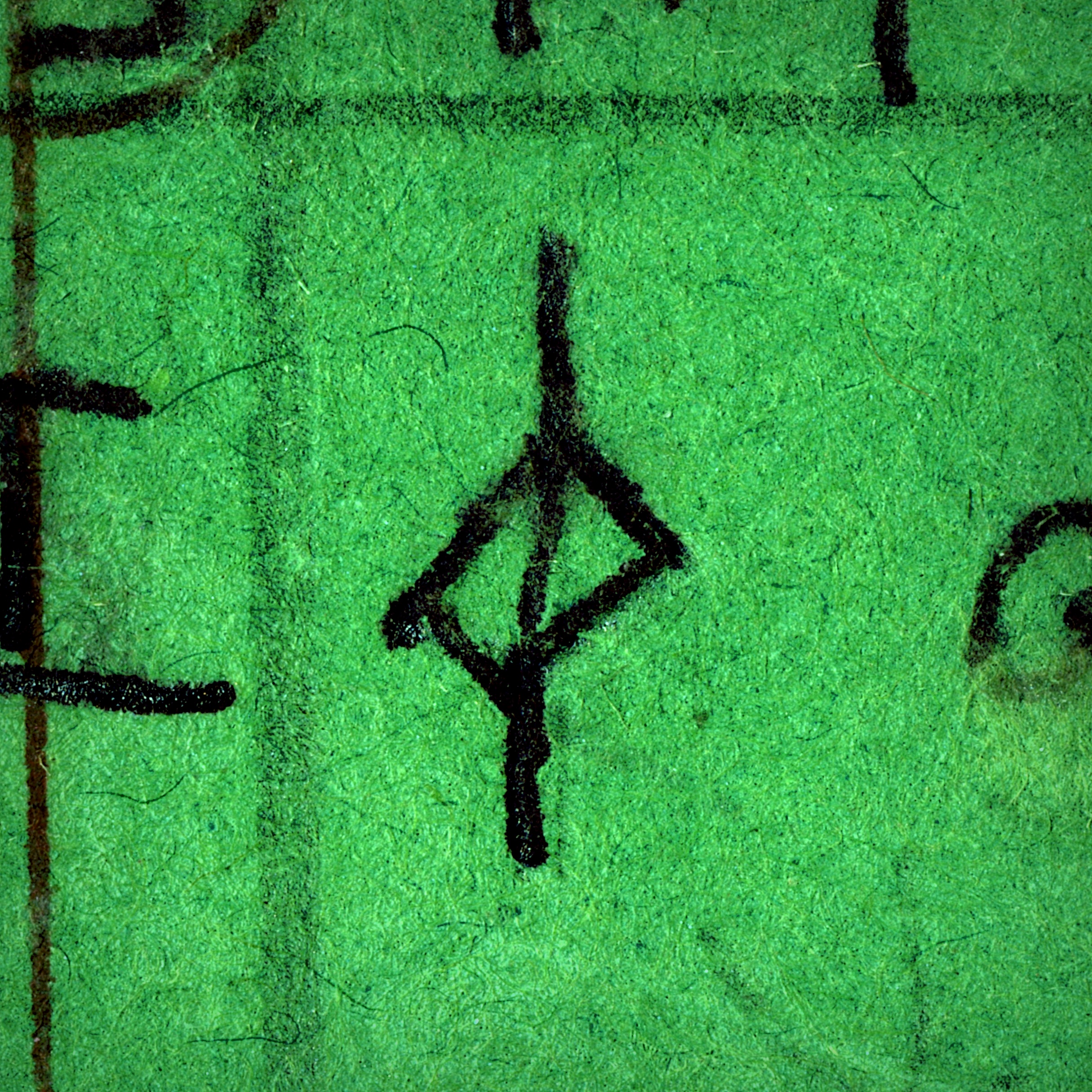

Ger is a little small. Look at it so teeny: ᛄ. You might not be able to see. It’s bigger now, it grew over time, but the poor thing was only half sized once. Sometimes Ger is carved to look like the rune for

Ger is a little small. Look at it so teeny: ᛄ. You might not be able to see. It’s bigger now, it grew over time, but the poor thing was only half sized once. Sometimes Ger is carved to look like the rune for

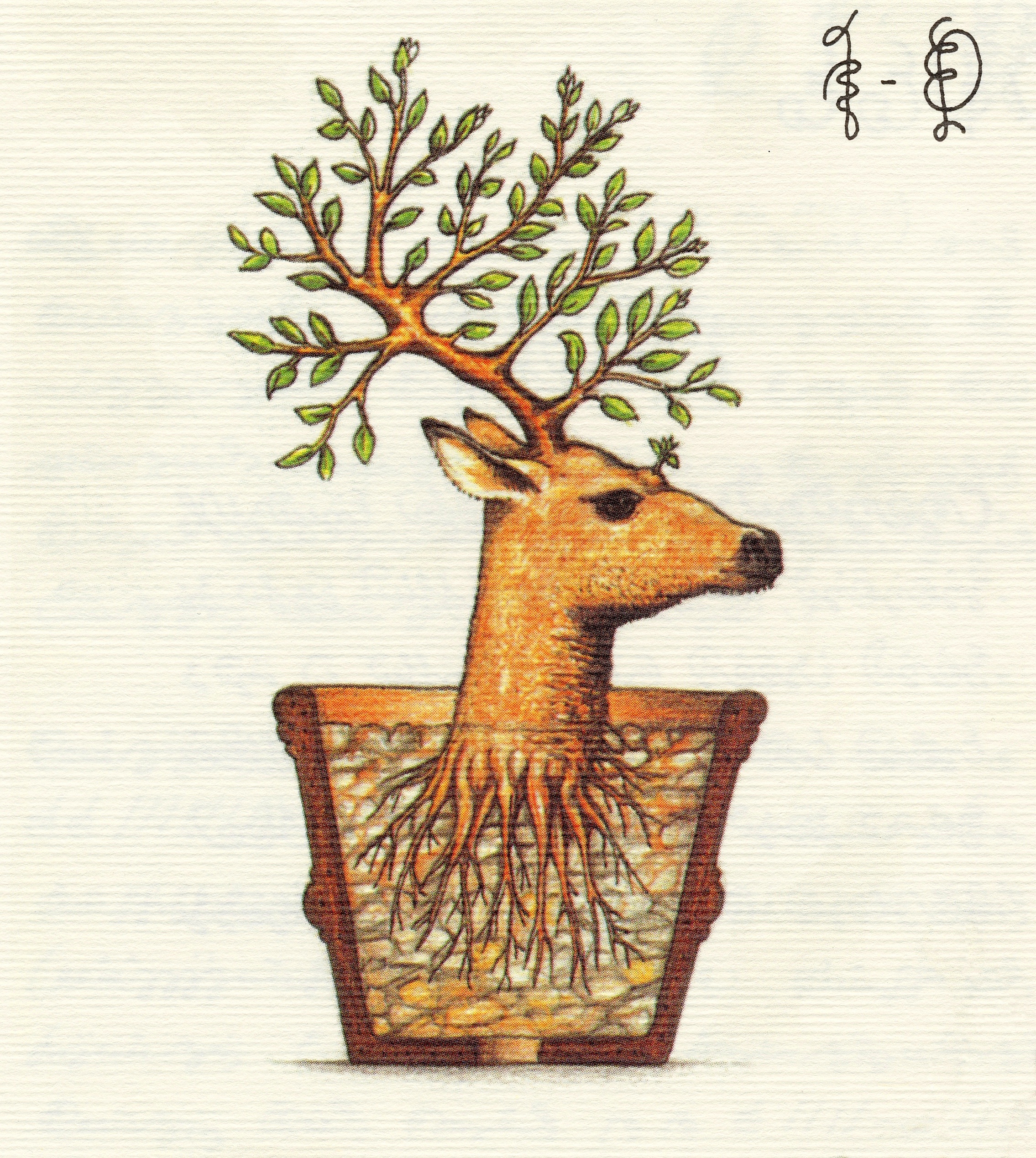

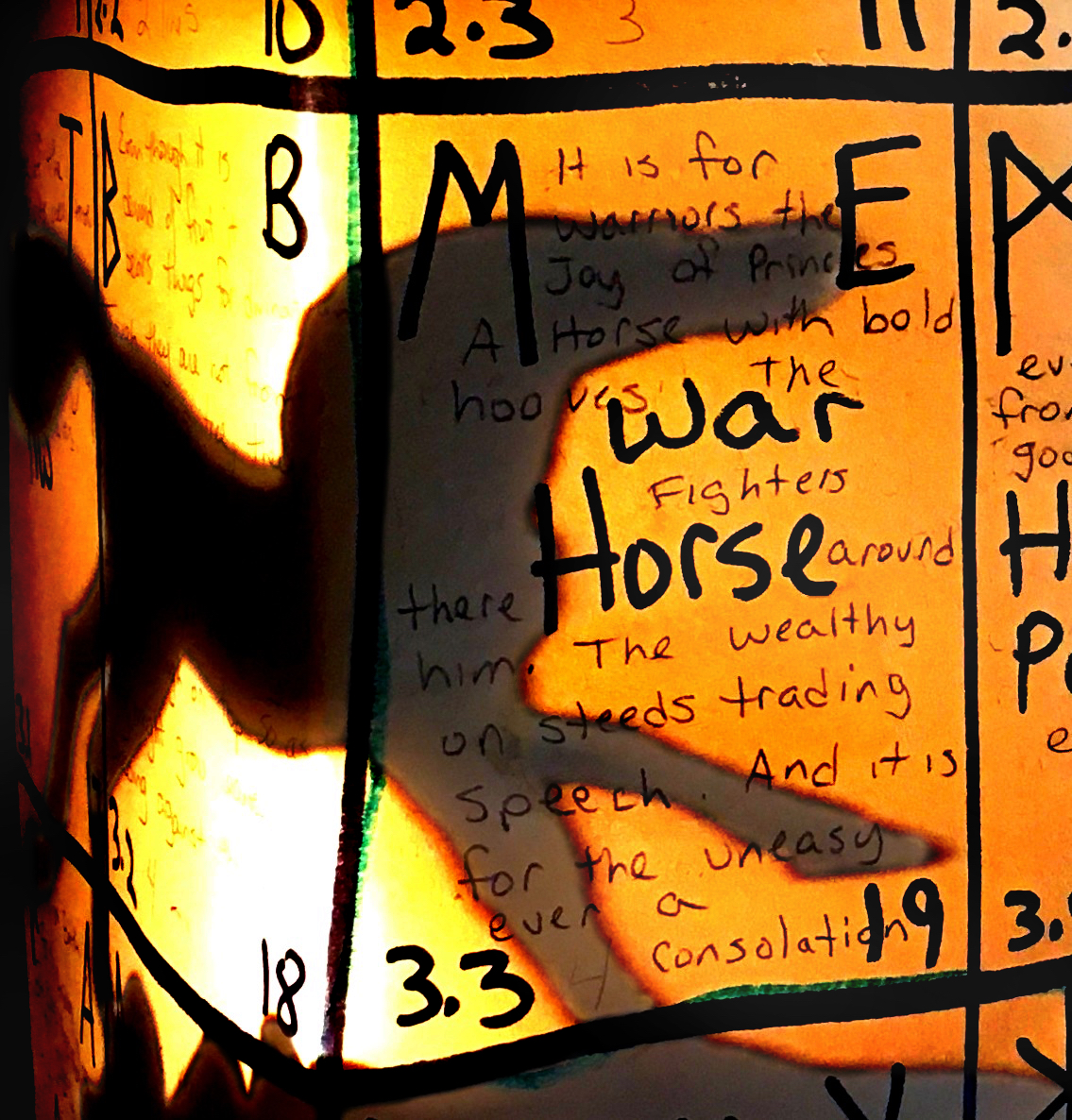

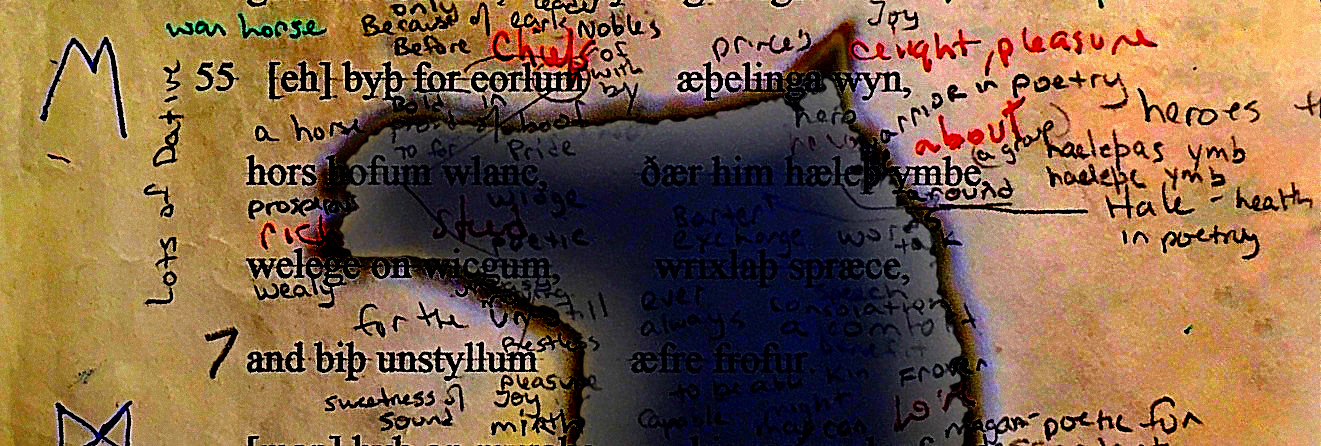

There’s lots of words for horse in Old English, hors, for one. But there’s wicg, hengest, friþhengest, onrid, radhors, mearh, sceam, steda, stott, blanca, gelew, all words that mean specific types of horses by the style, sex, physical appearance, color. This was a horse culture. Horses were a very big deal. Why? They made life easier. Having a horse changes everything. They were useful for pulling stuff, not for ploughing though,

There’s lots of words for horse in Old English, hors, for one. But there’s wicg, hengest, friþhengest, onrid, radhors, mearh, sceam, steda, stott, blanca, gelew, all words that mean specific types of horses by the style, sex, physical appearance, color. This was a horse culture. Horses were a very big deal. Why? They made life easier. Having a horse changes everything. They were useful for pulling stuff, not for ploughing though,  H: At the start of an Old English word, H is almost silent,

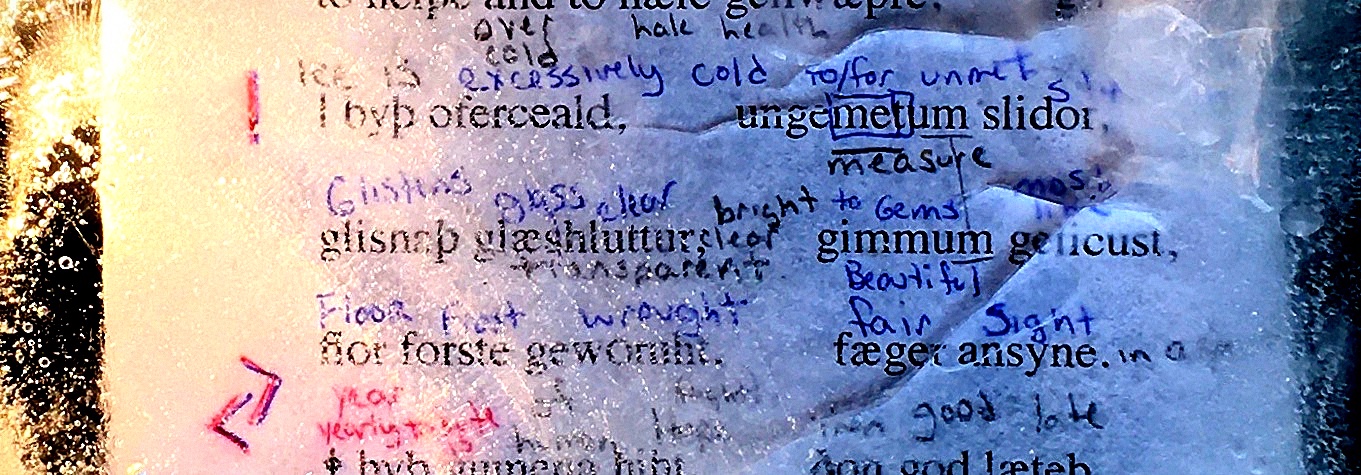

H: At the start of an Old English word, H is almost silent, During the time of the Rune Poem, a properly kitted warrior owned a decent war horse to take to battle. These were bigger horses than the usual so they could handle a person wearing heavy armor, and they could even bite and fight with their hooves. With the right war horse, you can be unstoppable. Almost. What can stop a war horse? Ice. Ice is brutal for horse hooves. It can ball up under their feet until they are teetering on their own personal ice cubes. Have you ever fallen on ice? That’s not a soft landing. A horse can easily slip and break a leg on the frozen dips and grooves in a road, and if they fall right through a frozen lake or river good luck getting them back out. Have fun with that. A war horse, large and powerful, formidable in battle, is handily defeated by ice.

During the time of the Rune Poem, a properly kitted warrior owned a decent war horse to take to battle. These were bigger horses than the usual so they could handle a person wearing heavy armor, and they could even bite and fight with their hooves. With the right war horse, you can be unstoppable. Almost. What can stop a war horse? Ice. Ice is brutal for horse hooves. It can ball up under their feet until they are teetering on their own personal ice cubes. Have you ever fallen on ice? That’s not a soft landing. A horse can easily slip and break a leg on the frozen dips and grooves in a road, and if they fall right through a frozen lake or river good luck getting them back out. Have fun with that. A war horse, large and powerful, formidable in battle, is handily defeated by ice. Vowel, high (mouth slightly open) front (tongue forward) unrounded lax (lips) = bit, unrounded tense = bite. Don’t bite your lips. I and Y were very similar in Old English,

Vowel, high (mouth slightly open) front (tongue forward) unrounded lax (lips) = bit, unrounded tense = bite. Don’t bite your lips. I and Y were very similar in Old English,

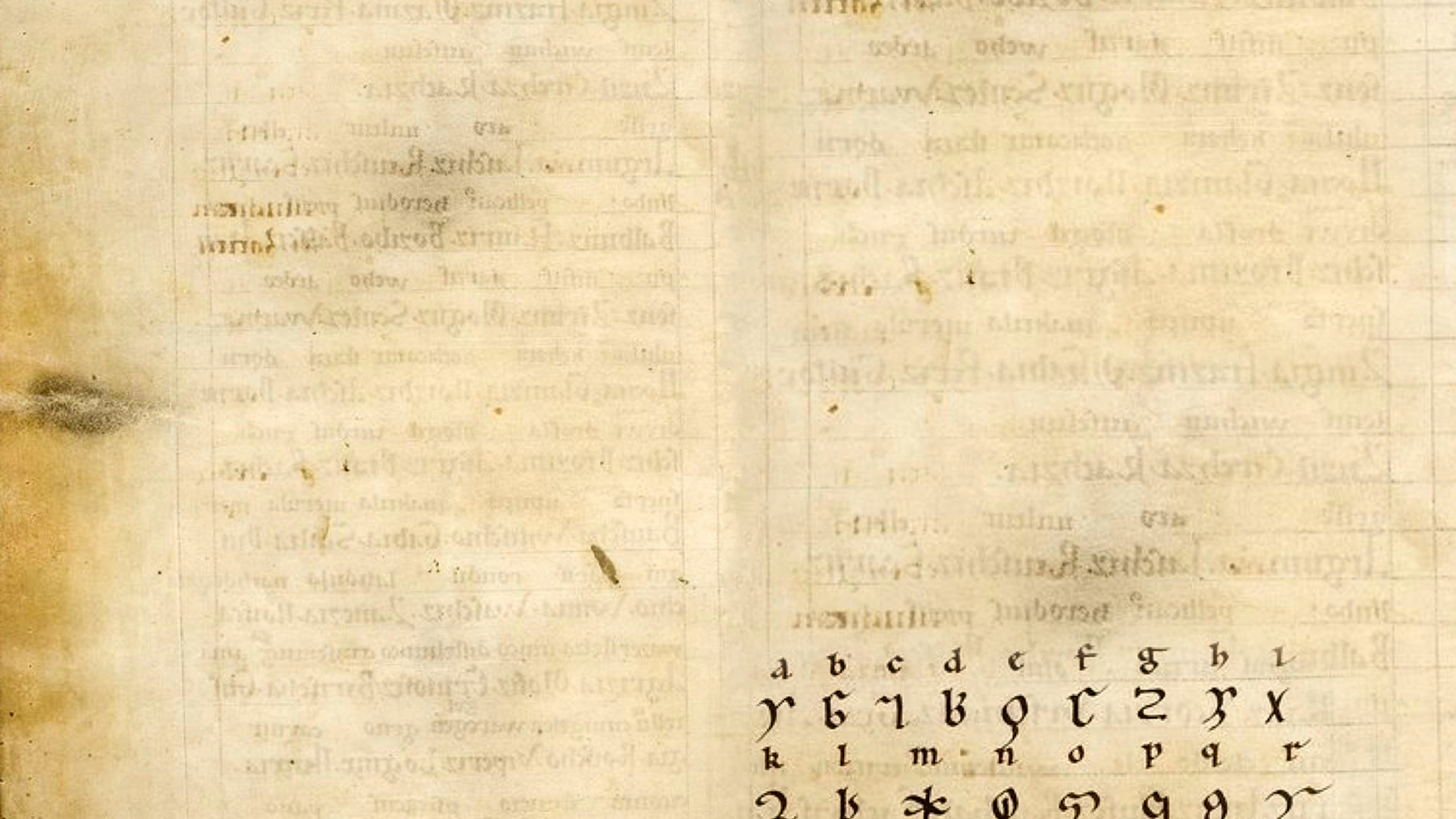

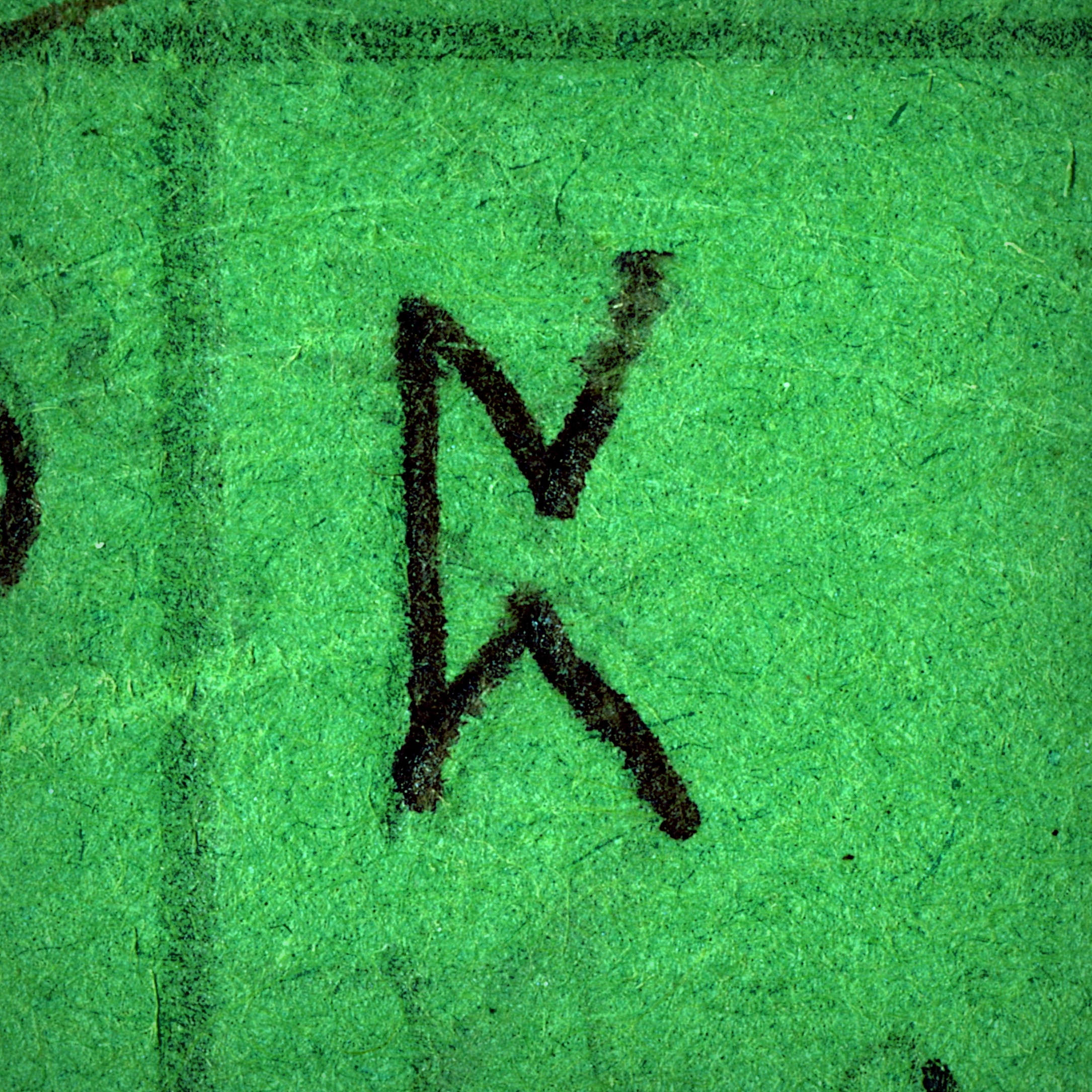

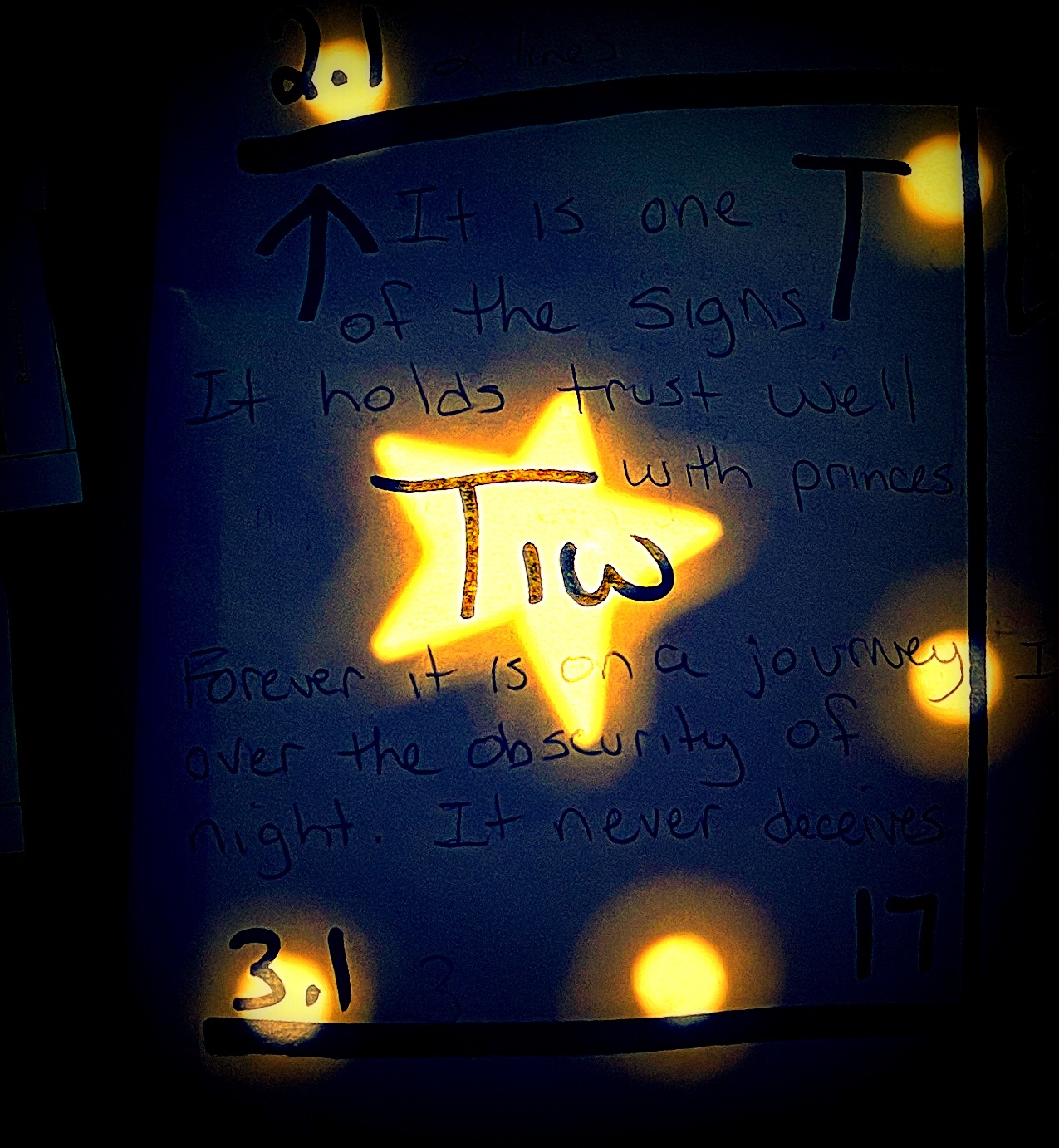

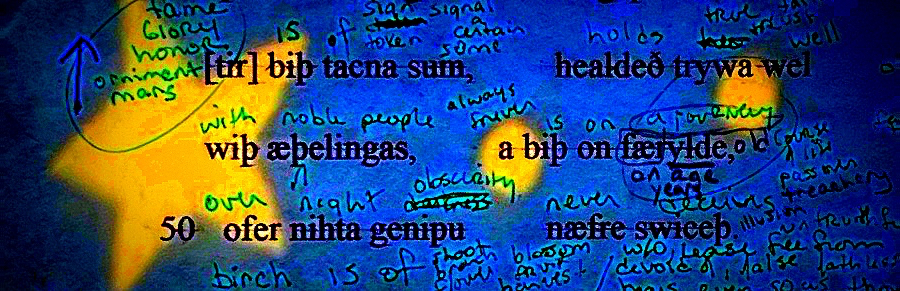

This is the rune for Eh, war horse, letter E. In the Cotton library manuscript called Galba A.ii (burned in a different fire from

This is the rune for Eh, war horse, letter E. In the Cotton library manuscript called Galba A.ii (burned in a different fire from